- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science and Technology

- Custom Article Title: Danielle Clode reviews 'The Best Australian Science Writing' edited by Bianca Nogrady

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

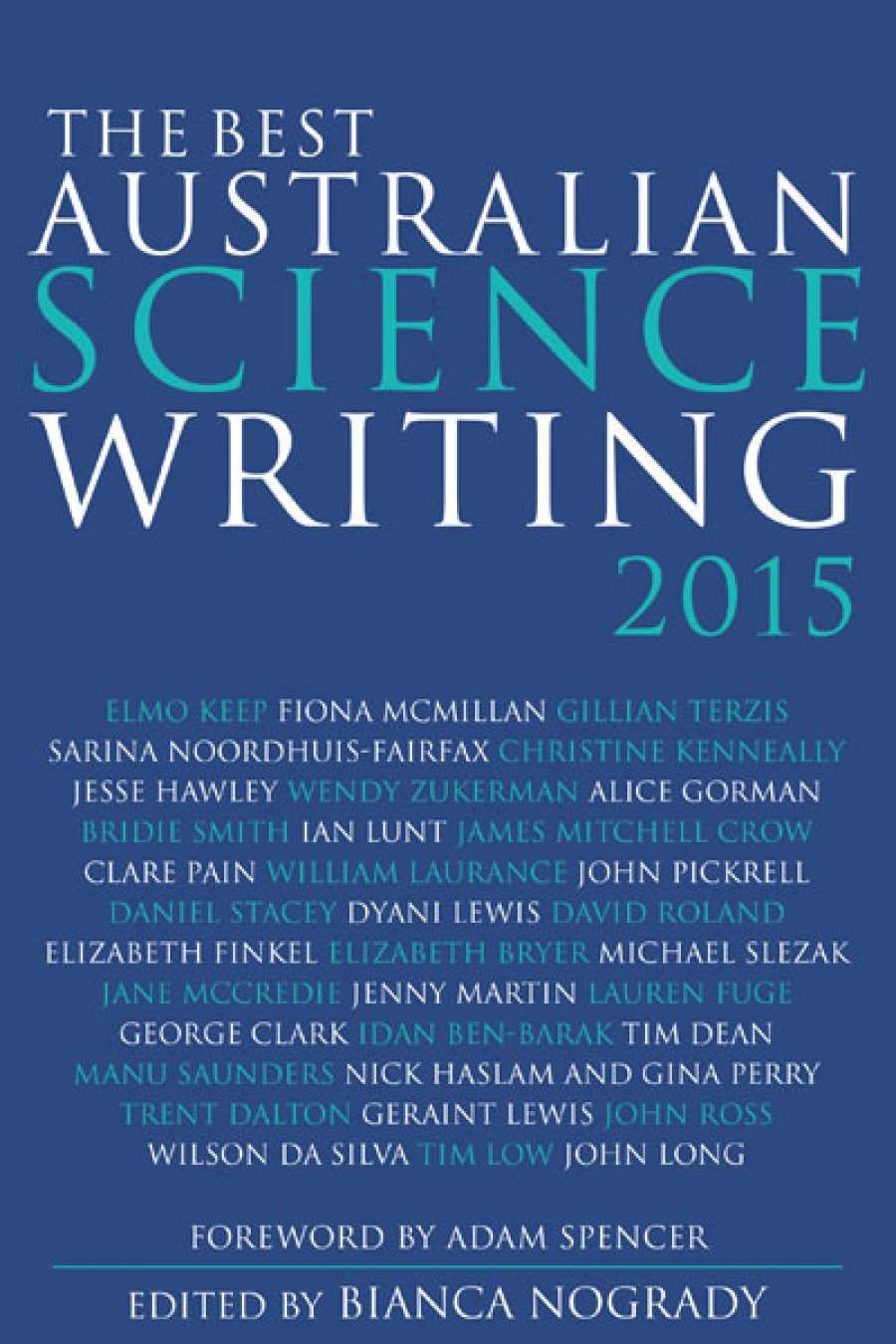

- Book 1 Title: The Best Australian Science Writing

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $29.99 pb, 301 pp, 9781742234410

The editorship of Bianca Nogrady has brought a tighter focus to the collection this year. This is, exclusively, an anthology of science writing, with no personal memoir or nature writing slipping in under the cover of ill-defined generic boundaries. Much as I love these genres, I think the collection is much the better for this clearer resolution. It presents science writing in all of its diversity and creativity – far from the steady diet of cheesy formulaic science journalism on which we were forced to survive in earlier decades.

Traditional media outlets like newspapers and science magazines (such as The Australian and Cosmos) make a strong showing, but they are rivalled by newer online outlets. A preponderance of blogs provides a new range of material, some of it very fine indeed, such as Elmo Keep's thorough investigation of a private mission to Mars, Jesse Hawley's worrying reflection on wetness, and Ian Lunt's enticing and humorous exploration of the future of field guides. But the inclusion of blogs does beg the question of the difference between published, self-published, and unpublished as selection criteria for the anthology.

More significant, perhaps, are the newer online outlets, like The Conversation, also founded in 2011. This curated news site has proven successful in providing scientists and other academics with a direct outlet for communicating their ideas with a broader audience. Their depth of knowledge and ability to synthesise that knowledge into more manageable concepts or metaphors gives them a natural advantage, as illustrated in William Laurance's account of the cancerous effects of roads on wilderness. Long derided as 'bad' writers, many scientists are also proving that communication is one of their core skills. Manu Saunders's 'Lost in a floral desert' illustrates Sharon Ruston's contention that 'we should neither dismiss the literary from the scientific nor the scientific from the literary', effortlessly incorporating Odysseus and D.H. Lawrence into her evocative description of the changing landscape facing native Australian pollinators.

'Were we missing great science writers like Primo Levi, Rachel Carson, or Carl Sagan?'

Other scientists reflect on the daily concerns of their own practice, including Alice Gorman, who pens an amusing future job description for a space archaeologist, and Jenny Martin, who offers a witty meditation on university performance measures as a powerful selection tool. The 'no-asshole rule', as a means of achieving gender equity in academia, is long overdue. Not that science writing should be restricted to scientists, by any means. That would preclude contributions like Elizabeth Bryer's delightful and expansive consideration of tool use, originally published in Kill Your Darlings.

Unlike many other kinds of writing, the strength of science writing comes not just from what is written and how it is said, but also who says it and where it is published. It is a shame, therefore, that publishers still like to tuck the author's biography and publication details at the back of the book, as if readers might be disturbed or distracted by such paratexual information.

'What strikes me overall about this eclectic and engaging collection is the importance of investment'

What strikes me overall about this eclectic and engaging collection is the importance of investment. The stories that work best are those that reveal a level of time and effort: an investment by the writer that pays off for the reader. Michael Slezak's travels in the wake of cane toad invasions leads us immediately into the landscape of northern Australia and into the company of a strange horde of frogs, toads, and ecologists. James Mitchell Crow's account of autonomous trucks on the Brisbane waterfront takes us into the unfamiliar heartland of futuristic oversized technologies. Others draw us into minds, rather than landscapes, like Trent Dalton's story of the tireless artificial heart and its equally tireless inventor, or Tim Dean's insights into the mind, and beliefs about the mind, of physicist Michio Kaku.

Good science writing takes time and costs money. Recognition, in a selective anthology like this, is wonderful, but we can only hope that it also helps foster an industry that remunerates its talented science writers and encourages them to produce more fine work in the future.

Comments powered by CComment