- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

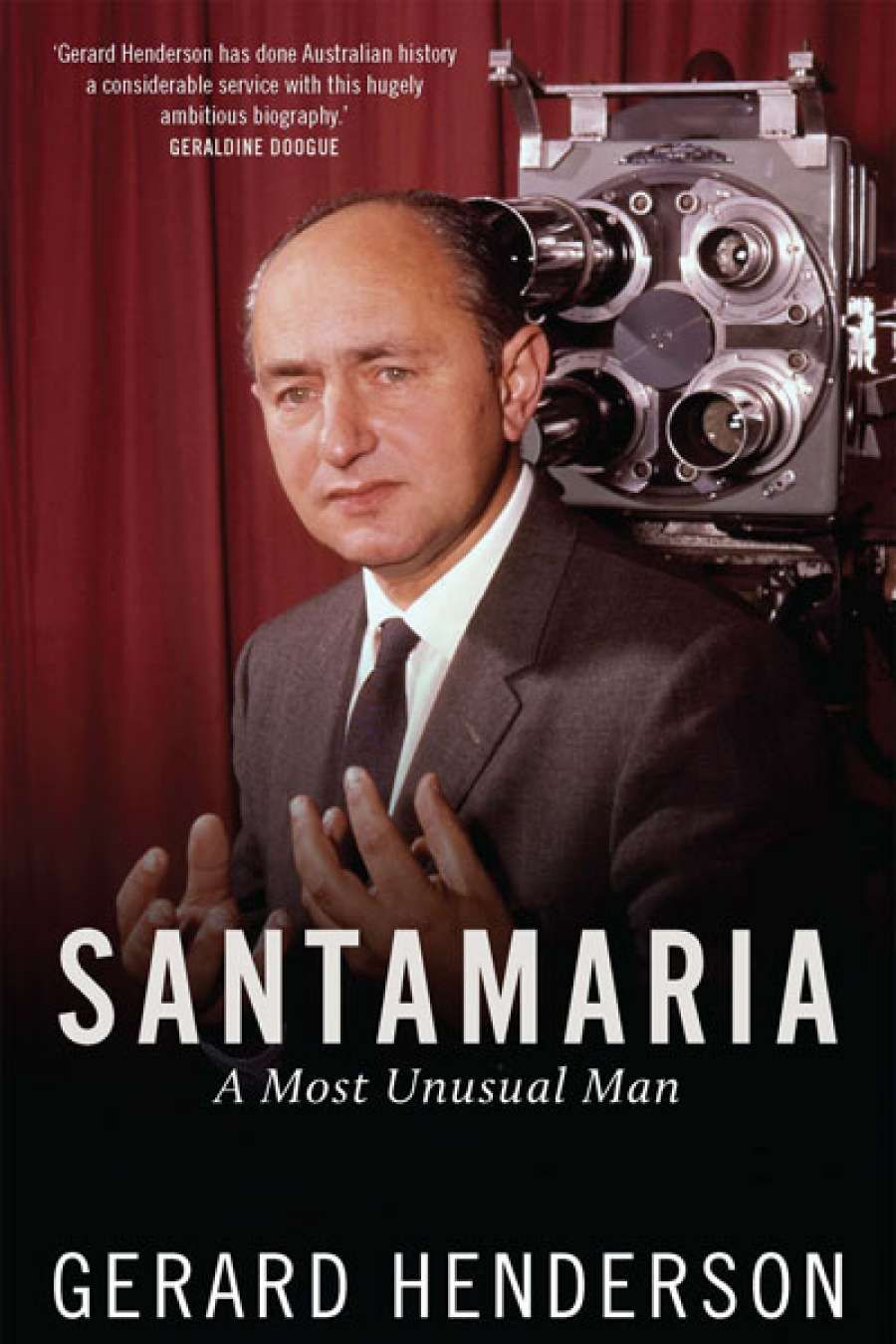

- Custom Article Title: Michael McGirr reviews 'Santamaria' by Gerard Henderson

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Santamaria

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Most Unusual Man

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $59.99 hb, 505 pp, 9780522868586

Henderson's dogged and fascinating book deals with a subject that is not only unusual but also difficult. Henderson is inclined to inflict enervating levels of detail on his reader. You can hardly blame him. Santamaria was omnipresent in Australian media for fifty years or more. But much of his work was done behind the scenes, even when they were scenes which he had created himself. In some ways, Henderson is trying to land a slippery fish. His net needs to be tightly woven, and it is.

Santamaria's public involvements are well known. He was easily the most prominent lay Catholic in Australian history, and his work in the so-called Movement led to the split in the Labor Party, the formation of the DLP and a long time in power for the conservative parties. He was a staunch opponent of communism and of many other things besides. His relationship with Archbishop Mannix, fifty years his senior 'was to be one of the most significant double acts in Australian history'.

B.A. and Dorothy Santamaria meet Pope John Paul II at the Vatican, 1992

B.A. and Dorothy Santamaria meet Pope John Paul II at the Vatican, 1992

'Henderson has an ambivalent relationship with his subject. This leads to some of the most intriguing storytelling in this biography'

Henderson has an ambivalent relationship with his subject. This leads to some of the most intriguing storytelling in this biography. He rightly takes issue with people who treat Santamaria with patronising mockery. Henderson takes Santamaria seriously. But this is not to say that his portrait is flattering. Indeed, at times it is withering; at others it has elements of high farce. The description of Mr Santamaria's arrangements for lunch at the offices of the NCC (National Civic Council) are a case in point. So too is a bizarre scene in which Santamaria wants to stop one of his minions from watching the cricket at the NCC office. Santamaria writes a circular letter which reads a bit like one of his jeremiads on Point of View, his famous weekly broadcast. This is not a trivial moment; it takes Henderson to the core of a profound problem: 'He just did not like one-to-one dialogue that would lead, in time, to a decision involving some degree of compromise. Laying down the line – easy. Engaging with critics, however sympathetic – difficult.'

The same could be said of many of Santamaria's professional relationships. He was a most effective communicator through the media – not so in person. Henderson's account of Santamaria's rapport with his hard-labouring and lowly paid foot soldiers is troubling. Santamaria did not readily acknowledge others. He was a one-man band and the band had a very limited range of tunes. He wrote his memoirs twice (1981, 1997) and did very little to include by name people who had made sacrifices of behalf of his cause.

Henderson has problems both with Santamaria and Santamaria's detractors. The biography draws a lot of energy from this tension. He notes that 'Santamaria, for all his high intelligence, did not really understand Australian society', and classes Santamaria among those idealists who 'tend to regard politics as being much easier than it really is'. Henderson offers a portrait of a weighty ego hiding behind 'mock humility'. Some of the most comic moments of the book relate to this. There is an account of an NCC seminar over a weekend in 1974 at which nine papers were on the program. Eight were delivered by Santamaria. The other was on the topic of hope, 'not a subject on which Santamaria claims any competence'. Exactly the same thing happened at a conference in 1954 at which Santamaria spoke for two full days. Yet he warned the likes of Tony Abbott and Greg Sheridan about becoming too prominent 'lest they become insufficiently humble'. He could not tolerate other voices or others' ideas. He was a pessimist, besieged by a 'crisis mentality'. He was not a creator. If much of this seems funny, it is a sorrowful kind of humour.

There is a great deal to ponder in this hard-working and sometimes obsessive biography. I know enough of Santamaria's family to know how warm and affectionate his children were towards him. But much of this book is not so sunny. Like many polemicists, Santamaria divided his world between 'them' and 'us'. Henderson describes him as a 'fine writer'. This is not my experience of Santamaria's shrill, metallic prose. He spoke and wrote a lot about freedom, but this biography is by no means a portrait of a free man. The descriptions of his brand of Catholicism reminded me of a person who bought a house so he could admire it and even defend it from the outside, but never really looked inside. His faith seemed almost a series of policies or pronouncements. There appeared to be little in it about love, relationships, forgiveness, longing, reconciliation, or community. His faith sustained him, but he seemed unable to taste its many subtle flavours. Perhaps there is more to the story than Henderson tells. But it is hard to imagine anyone going to greater lengths than Henderson did to find out.

Comments powered by CComment