- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: James Walter reviews 'Keating' by Kerry O'Brien

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

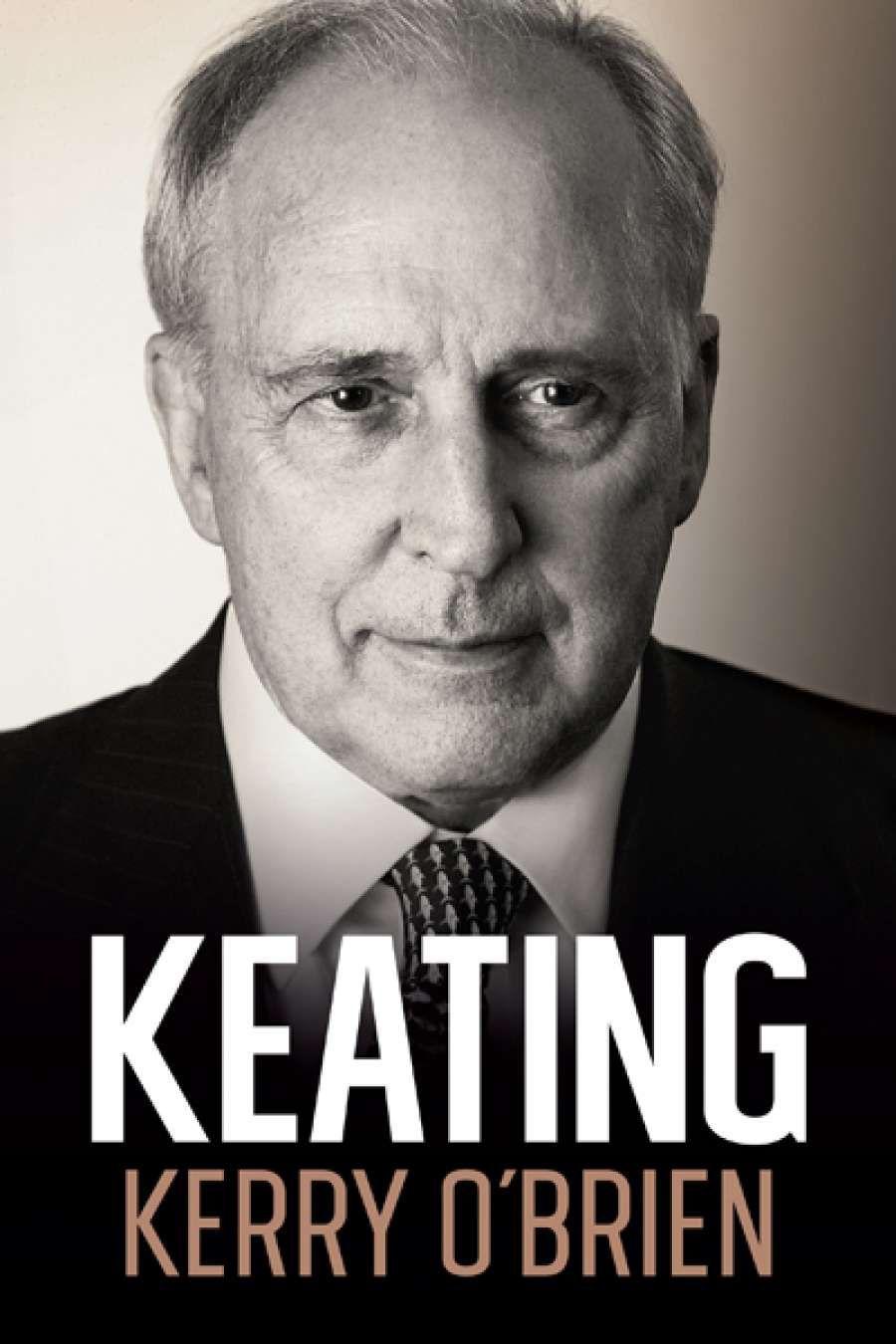

- Book 1 Title: Keating

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $49.99 hb, 806 pp, 9781760111625

This approach allows Keating to assert his legacy, to talk at length about the significance of what he did and to present an extended dissertation on the exercise of power. Having, while in office, educated the press gallery and then the public about the imperatives of what must be done, he will now educate contemporary readers about the long-term importance of his enterprise: now he is 'speaking' history.

For those who lived through those times and who followed the action, we are on familiar ground. O'Brien takes Keating methodically through the great policy debates of the 1980s and 1990s, and the controversies and rivalries that are already well covered in many earlier works. What we get, though, is nonetheless invaluable: Keating's take on his intentions, his practices, his interpretation of people and events. His articulateness and ferocious intelligence are manifest. It is a rich source for political junkies (see the exhilarating account of how to achieve psychological dominance in parliament in 'The Politician and the Professor') and for serious researchers (a thorough index enables them to mine particular themes or policy interests: in doing so they will find much with which to take issue).

Still, it is heavy-going. First, it is a doorstopper. How many will persist, one wonders. Second, while O'Brien asks the right questions, he doesn't push Keating hard enough when he sidesteps issues. Third, Keating's preoccupation with insisting that he was the driver of everything that was achieved, and with denigrating Hawke seems increasingly intemperate. Fourth, Keating's insistence that 'this was me ... and this, and this, and this' becomes not only tiresome, but also implausible. Let me elaborate on some examples.

'Keating's preoccupation ... with denigrating Hawke seems increasingly intemperate'

One of the questions O'Brien returns to several times is what Keating felt for those adversely affected by the structural changes he instituted, especially in their impact on the labour market and on income distribution. Keating mostly begs the question, asserting that he increased the prosperity of the country and generated more and better jobs. O'Brien might have pushed him harder on the recessions, periodic spikes (to record rates) in unemployment, crushing interest rates, and the fact that real wages of average adult male workers stagnated between 1975 and 1995, while those earning the lowest wages experienced a decline (see Ian McLean's Why Australia Prospered, 2013).

Then, when finally recognising the need to address the problem of the long-term unemployed, with the Working Nation program following the 1993 election, Keating claims it as all his own work: 'I was disappointed with the departmental drafts ... In the end ... I constructed the Cabinet submission myself ... I had in my head the whole sense of the Cabinet discussion and the whole development of the policy ...' This is at odds with most other accounts (see for, instance, the representation of Working Nation as a case study of collaborative policy development in Meredith Edwards's Social Policy, Public Policy, 2001). One could cite other instances: the index, as noted, is most useful for cross-referencing Keating's recollections with other sources.

Paul Keating, 2007 (photograph by Idpercy via Wikimedia Commons)

Paul Keating, 2007 (photograph by Idpercy via Wikimedia Commons)

Another poser is Keating's preoccupation with his legacy war with Hawke. Keating's argument that Hawke generated the 'political capital' that allowed his Labor government to prosper, while Keating took many of the bold initiatives that 'spent' it, is persuasive. Every other source concedes that their partnership was integral to what was achieved. But Keating will not let it rest there. Since many other sources show Hawke's management of and delegation to a talented team to have been one of his strengths, Keating's repetition of such claims as Hawke 'had me to super-intend the whole policy framework and identify the broad philosophical directions' denies credit to one of the most productive Cabinets we have seen. To assert in addition that Keating set up the conditions for virtually every one of Hawke's election wins from 1984 onwards further strains credibility: Hawke's command had faltered sufficiently by 1991 for Keating's deposition to succeed, but to argue that he had been propped up by Keating since 1985 beggars belief. Keating's own speculation about what was going on – that much can be understood in terms of Hawke's narcissism and jealousy (of him) – gives us a clue to the dynamic here.

Hawke's overweening self-regard and confidence undoubtedly fostered success. The core of his narcissism, apparent in both Hawke's memoir (1994) and Blanche d'Alpuget's first biography (1982), was the love and over-indulgence of his parents, especially his mother. The outcome was the sense of destiny that so struck Keating: 'He actually thinks he is, of his essence, a special person ... Bob thought he was owed everything.' The paradox, however, is in how Keating parallels Hawke. Keating attributes his own drive to the love of his mother and grandmother: 'I walked around with grandmotherly and motherly love ... it ... gives you that kind of inner confidence ... you go through the fire but you're not going to be burned because somebody loves you.'

How, then, did Keating, so carefully cosseted as to feel himself 'special', avoid Hawke's egotism? What gave him the 'humility' that he repeatedly insists is his in the face of O'Brien's probing of his own egotism? The difference, according to Keating, was that he did things the hard way: despite that 'inner confidence', everything had to be earned, whereas Bob 'had everything handed to him on a plate'.

'How, then, did Keating, so carefully cosseted as to feel himself 'special', avoid Hawke's egotism?'

Arguably, the distinction is this: Hawke's experience was of unconditional love and a consequential over-estimate of his ability to master the world. In contrast, while Keating's grandmother was a source of unconditional love, there is a hint that his mother's investment had to be earned, since it came with a rider – her talented son would achieve the heights unattainable to a woman of her generation. Hence the enormous drive, the self-acknowledged search for 'perfection', but (one suspects) also the periodic disillusion and disengagement: nothing would be good enough.

There is a trope about over-invested mothers and driven sons that is a constant in our culture, from high tragedy (Hamlet, Coriolanus), to melodrama (the noir movie White Heat, 1949), to comedy (The Blues Brothers' farcical mission from their 'mother'). Keating's relentless monomania here reminds us of the remarkable final scene in White Heat. Jimmy Cagney's gangster protagonist, whose maternally induced drive to reorder his world ends with him wounded and trapped by police on top of a huge spherical gas tank, refuses to surrender. He fires into the tank, and in the moment before its explosion bellows to his audience, 'Top of the world, Ma!' Keating will keep replaying his battles, to 'educate' us, to insist that he remains 'top of the world' he did so much to shape.

Comments powered by CComment