- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

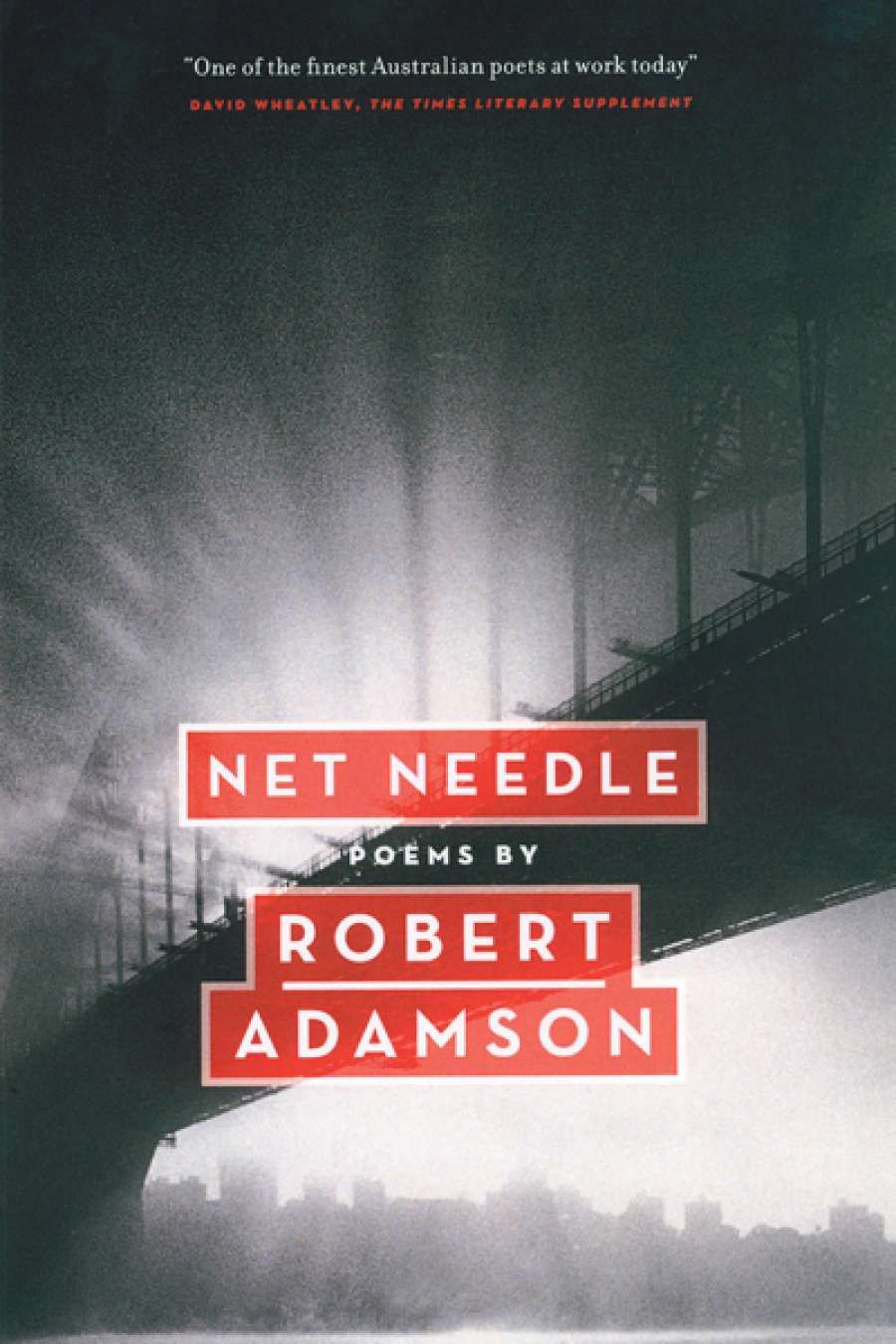

- Custom Article Title: A.J. Carruthers reviews 'Net Needle' by Robert Adamson

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Net Needle

- Book 1 Subtitle: Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $22.99 pb, 96 pp, 9781863957311

One of Adamson's most experimental books, Waving to Hart Crane (1994), tested the limits of poetic form in interesting ways. His formal interest in Creeley-like thin lines harks back to earlier poems that appear in Waving. Poems like 'Webb's Head', 'Anthropomorphic', 'The Kingfisher', and 'Through the Coddling Night' deploy a sparing, even minimalist, use of words.

In Net Needle, 'Harsh Song' sports such needle-thin lines. There is a verbal complexity in 'leather', which sonic pre-empts 'ratchet, or', or only just (readers will pick up their own echoes). At these points the reader is inclined to play with (or feel playful within) language. Sonically derived geometries of attention continue in the second half: 'whispered / sounds, / a smoker's / thick / exhalation – / bowerbirds / in the grapevine.'

Poems are shapely things, things to be looked at as much as read. The poem also has a slight arch: the slight bend in its middle where the right-hand margins resemble a convex lens. The beginning and end of the poem are carefully considered (I thought 'Afternoon's / pulse' might have occupied a single line, but then the reason for the rhythmic break becomes clear). Likewise for the more explicit caesurae after 'susurration –', 'mouth –', and the breath required after 'exhalation –' marked, as it were, by a dash.

The notion that the above poem looks like a convex lens might seem less fanciful in light of 'Spinoza', which engages European philosophy and optics. Examining a peregrine falcon, the poem's couplets read as spatially resonant and sharply scopic:

travel by light

shooting

through veins

and gelatinous

floating lenses

the packed neurons

composing

the optic nerves

of a peregrine's

four-dimensional sight

'Poems are shapely things, things to be looked at as much as read'

Here, Adamson is addressing Spinoza, the philosopher, via poetic optics. This could be said to be 'phenomenological', concerned with sensory properties in relation to consciousness, but these might also be 'Objectivist' aims. Louis Zukofsky, in 'An Objective' of 1930–31, famously described the program as follows: 'An Objective: (Optics) – The lens bringing the rays from an object to a focus. That which is aimed at. (Use extended to poetry) – Desire for what is objectively perfect, inextricably the direction of historic and contemporary particulars' (Preposition 21). So too, in 'Spinoza', there is a sense that the object of enquiry here is the gaze of the animal, with the descriptors focused on the (invisible) optic nerves of the peregrine.

As I read it, Adamson is at his best when he eschews the romanticism of conventional verse style and explores the grittiness, impurity, and sheer difficulty of language. When drawing on these elementary impulses (for, indeed, children love playing with language), Adamson can afford delight to all the senses. John Tranter has situated Adamson in the 'Australian Tradition', a tradition which has resisted the 'tidal wave of avant-garde experiment' as it 'surges into the future', but much of Adamson's poetics must sit uneasily within this designation as well. This is not to say that Adamson is an experimental writer, but readers and critics might find pleasure in those playful and innovative aspects of his writing.

Comments powered by CComment