- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Jake Wilson reviews 'Directory of World Cinema, Volume 19' edited by Ben Goldsmith, Mark David Ryan, and Geoff Lealand

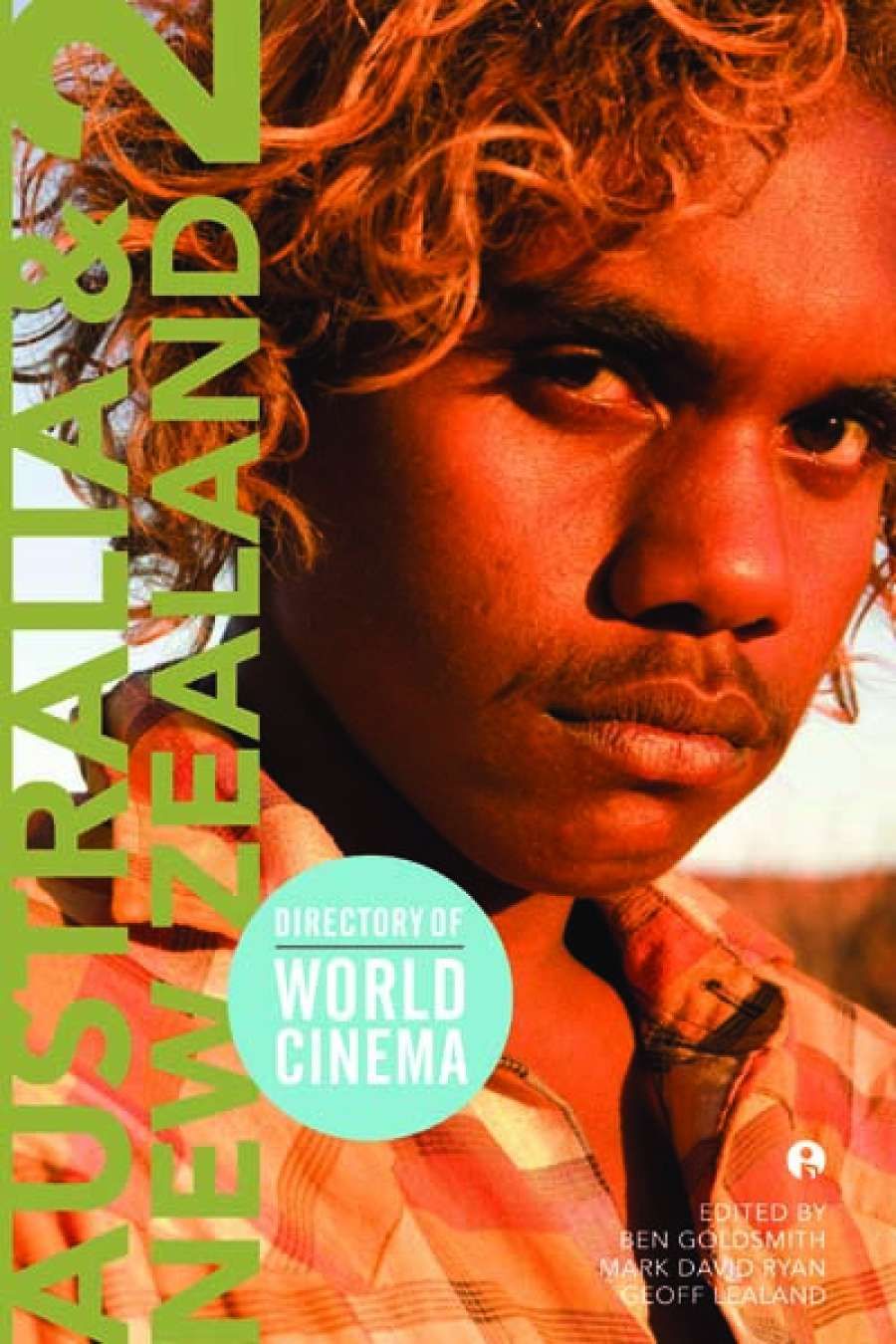

- Book 1 Title: Directory of World Cinema, Volume 19

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia and New Zealand

- Book 1 Biblio: Intellect (Footprint), $69 pb, 364 pp, 9781841506340

Still, these particular two directories do help fill a gap. There has been much excellent writing on Australian cinema, but no single volume can be recommended as an up-to-date guide (the nearest would be the 1999 Oxford Companion to Australian Film, which cries out for a second edition [Quite! Ed.]). Critical attention to New Zealand cinema has been more intermittent, though there has been a flurry of publishing activity just recently, as Geoff Lealand, the Kiwi among the editors, points out here.

In their introduction to the book's Australian section, Lealand's fellow editors, Ben Goldsmith and Mark David Ryan, ponder the question of what constitutes an Australian film. While no easy answer is forthcoming, they do offer a distinctive, populist take on the field. The emphasis is on films from the 1980s and after; as in the 2010 volume, most of the space is occupied by a series of chapters examining various genres, including supposed 'trash' genres such as action and horror.

While the short shrift given to Samson & Delilah may well be inadvertent – perhaps a contributor dropped out at the last minute – it is consistent with the impression which the book conveys of viewing Australian cinema primarily from an 'industry' perspective. There is no chapter dedicated to the art movie, or to indigenous film-making (not genres in the commercial sense, but surely important strands of Australian cinema all the same). There is also no chapter on Australian documentary, a glaring absence in the 2010 volume as well. Australian experimental film does slightly better, with Adrian Danks's overview of the work of Arthur and Corinne Cantrill packing an impressive amount of insight into a small space.

'These ... directories do help fill a gap'

The New Zealand section, which occupies less than a hundred pages, takes a different tack. Again the emphasis is largely contemporary, but with much more material on low-budget independent film-making, especially by women: this is where I, as an Australian reader, had most to learn. The strongest pieces include Martin Rumsby's concise but useful guide to New Zealand experimental cinema and Sylvia Lawson's characteristically eloquent introduction to the essay films of Annie Goldson; significantly, Rumsby and Lawson are both non-academics, unlike the vast majority of contributors to the book.

Jane Campion (photograph by Piotr Drabik via Wikimedia Commons)

Jane Campion (photograph by Piotr Drabik via Wikimedia Commons)

In fairness, there are few traces here of the theoretical jargon favoured by film scholars a generation ago. Instead, much of the writing hovers between wooden neutrality and a brazenly upbeat brand of industry-speak – the latter at its purest in Tess Van Hemert's glowing account of the Brisbane International Film Festival, which ignores the controversies that have plagued the festival in recent years, culminating in its comprehensive rebranding in 2014. Negative criticism of any kind tends to be muted: of the sixty-odd reviews of individual films, none are unmitigated pans, though it is clear that finding things to praise was sometimes a struggle.

It is clear, too, that a nominally populist outlook can all too easily co-exist with very conventional assumptions about particular genres. Thus historical dramas such as Balibo (2009) or The Lighthorsemen (1987) are described as 'deeply moving' or 'beautifully filmed', while the action specialist Brian Trenchard-Smith – one of Australia's most formally inventive film-makers – is condescendingly labelled a purveyor of 'higher level exploitation' with 'no pretensions about his work'. Ryan at least gets to show his credentials as a horror buff, mounting a defence of the visual aesthetics of Russell Mulcahy's Razorback (1984).

'Much of the writing hovers between wooden neutrality and a brazenly upbeat brand of industry-speak'

But a critical approach that presumes the existence of a permanent split between high and low culture is doomed to irrelevance whichever side you profess to champion. If anyone here suggests a way out of the impasse, it is the British scholar Jonathan Rayner, as primary author of an incisive chapter on Australian Gothic cinema. Persuasively, Rayner identifies the Gothic as a 'universal' tendency in Australian film-making: less a genre than a contagion that spreads across many genres, infecting them with 'uneasy, uncanny and unpalatable elements'.

Collapsing realism and fantasy, satire and horror, art and pulp, the Gothic poses a challenge to the very notion that Australian cinema can be straightforwardly carved into discrete segments. And what about New Zealand cinema? Well, this too has its Gothic aspect, exemplified by Jane Campion's The Piano (1993) – analysed, as it happens, in the Australian portion of the book, as if to show that the borders between national cinemas are blurred in much the same way.

Comments powered by CComment