- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Jane Grant reviews 'Modern Love' by Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Modern Love

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Lives of John and Sunday Reed

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $45 pb, 418 pp, 9780522862812

Much of the book will be all too familiar to readers of previous histories. The Heide of Modern Love is once again an Eden in the creative wilderness of mid-twentieth-century Australia, where the patrician Reeds aesthetically, intellectually, and financially nurture the talents of a circle of young pioneering artists. Sam Atyeo paints his abstract Organised Line to Yellow after reading the Reeds' copy of Herbert Read's Art Now; Sidney Nolan paints his first Ned Kelly series on the Reed dining room table; Sunday seduces Atyeo, Nolan, and others; and Joy Hester sketches by the library fire as Nolan, Albert Tucker,and the Reeds argue about politics and art. Nonetheless, Modern Love is a clever synthesis of the secondary sources and it does deliver a fast-paced narrative.

Sunday's childhood in Toorak and unhappy first marriage, and John's equally wealthy Tasmanian childhood and English education, neatly interweave before their meeting and marriage in 1932. Harding and Morgan's usage of the fascinating and at times critical letters of Cynthia Reed, John's writer sister, explicate the territorialism of the Reeds, and significantly draw this intriguing and overlooked cultural figure a little more into the foreground. The late years, describing the suicide of the Reeds' adopted son, Sweeney, the natural child of Tucker and Hester, are also movingly told, and illuminating. John Reed's blaming of Sweeney's rebellious behaviour on Hester's genes rather than on his upbringing gives insight into the complications of the adoption and Reed's resistance to taking responsibility.

It is a pity, then, that the same critical distance is not extended to Sidney Nolan. Instead, his departure and marriage to Cynthia Reed in 1948 is all too predictably seen as a 'betrayal': their breach blamed on Sidney's 'shame' and Cynthia's '"vituperative" attitude towards John and Sunday'. No alternative perspective is proffered. The authors sweep over the personal and sexual politics of Heide: the significant age differences between patrons and protégés, and the inequalities of class and financial dependency. They avoid any discussion of the ethics of Heide which might unsettle our sympathy for the Reeds.

'Modern Love returns us to the domestic interiors of Heide as creative fulcrum'

The much more controversial and problematic claims of Modern Love, however, arise from their use of a taped interview with the journalist and former Heide resident Michael Keon, conducted by historian Richard Haese in the 1990s and until now never used. Keon recalls Reed talking to him about: '"physical socialism" ... and soon grasped ... that he wished to be present while he and Sunday made love ... It also dawned on Keon that this would not be a new experience for the Reeds, but was a practice they had already engaged in with Nolan, if not Atyeo.' It is a bit odd that the authors paraphrase rather than quote a revelation of voyeurism which is so important to their portrait of Reed, but it all seems to makes absolute sense to Harding and Morgan: John Reed, they note, was a birdwatcher, and 'a fundamentally visual person ... whose aestheticism was part of his very essence'.

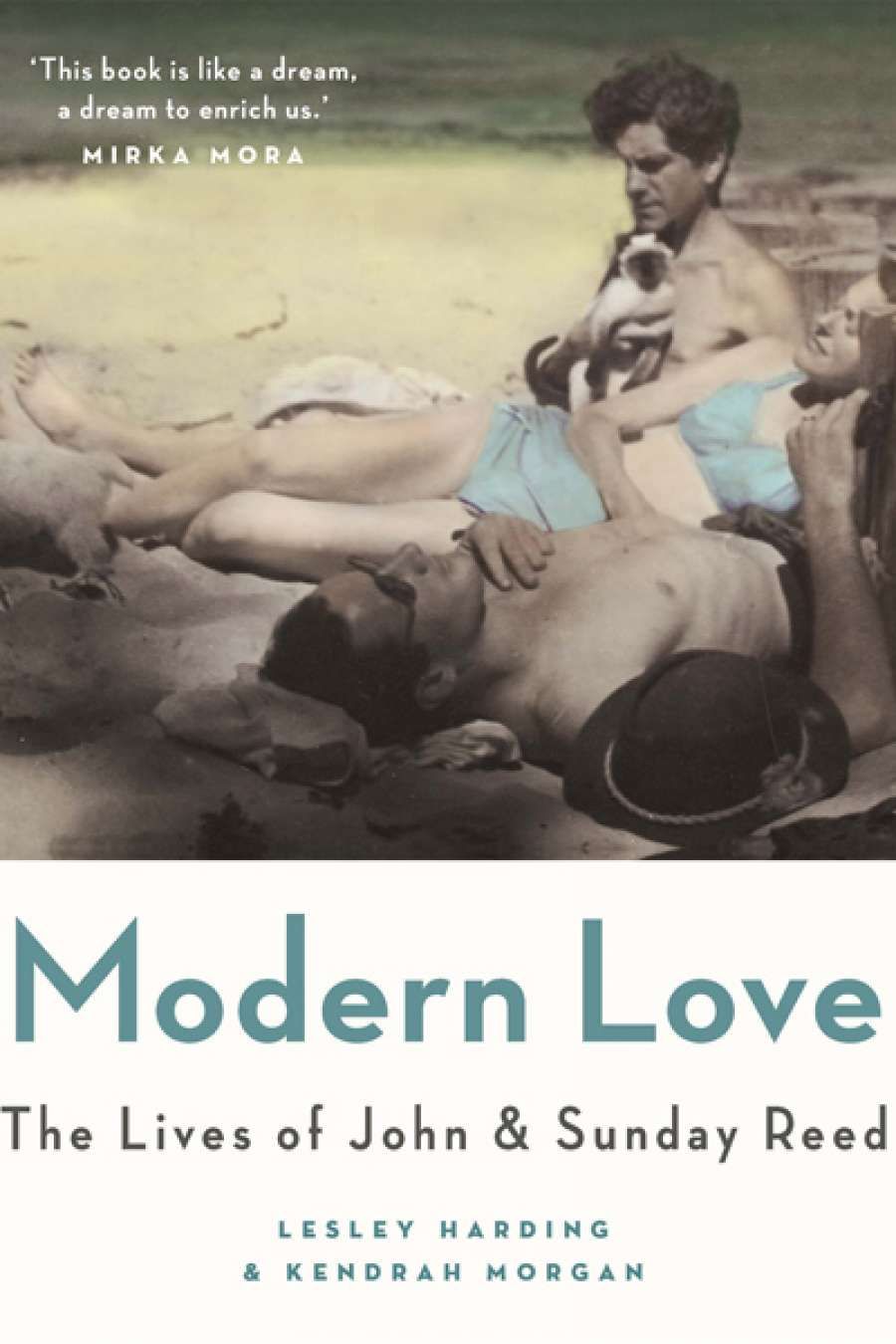

John Reed, Sidney Nolan, and Sunday Reed, at Heide, 1942 (photograph by Albert Tucker, National Library of Australia, via Wikimedia Commons)

John Reed, Sidney Nolan, and Sunday Reed, at Heide, 1942 (photograph by Albert Tucker, National Library of Australia, via Wikimedia Commons)

Keon is a witness in the 1940s to further 'Bacchanalian' excesses at Heide between Joy Hester and Sunday Reed: 'Neither woman attempted to hide it; it was taking place "on the couches – in the living-room – over the refectory table – anywhere that happened to be handy".' The desecration of the table where Nolan painted the first Kelly series is a nice touch in what sounds like an old man's revenge fantasy. Keon is not a credible witness and had good reason to dislike the Reeds. As we learn a number of pages later, he was proving troublesome, so the Reeds accused him of stealing and kicked him out of Heide. Such scenes of unbridled public passion also give rise to the contradictions which confuse Sunday's character in Modern Love. By the authors' own account, Sunday is mildly homophobic, intensely shy and so outwardly conventional that she insisted poet Max Harris and his girlfriend Yvonne Hutton sleep in separate bedrooms when they stayed.

'They avoid any discussion of the ethics of Heide which might unsettle our sympathy for the Reeds'

Modern Love is such a curious blend of protectiveness and exposé. Possibly it was rushed, or the authors, who are curators at Heide, were under pressure as to its purpose and effect. Biography is clearly difficult to get right. It takes a great deal of time to research, and to manage what David Ellis describes as its 'contradictory aims: to be scrupulous in the use of evidence but at the same time provide a readable narrative' ('Biography and Gossip', The Cambridge Quarterly Review, 1995). Harding and Morgan certainly deliver a 'readable narrative', but their stretching of the facts to fit is all too evident. Unfortunately, in presenting this as a work of new scholarship, their authority is compromised by the use of unreliable sources as evidence.

Keon's questionable accounts of voyeurism and lesbian romps will, no doubt, only inflate the mythology of the scandalous Reeds. Allegations made about poet and librarian Barrett Reid and his relationship with the ten-year-old Sweeney, however, are much more serious and disturbing: 'A number of people believe that tragically, by this time, he had been "interfered with" by Barrie, which could explain his sexually precocious behaviour. The Reeds were unaware that anything untoward had transpired and continued to encourage Barrie's involvement in Sweeney's life.' No sources are cited, presumably because, without evidence, none of the interviewees was prepared to put his or her name to the shredding of a dead man's reputation. But Harding and Morgan have been prepared to do so here. Reid, it seems, is just another sensational piece in the sexual 'jig saw' puzzle which Heide has become. There is a troubling absence of feeling for the effect this book might have on Reid's reputation; or, as significantly, on the living close friends and relatives of those whose real or imagined private lives Modern Love exposes and traduces. It lingers long after one finishes the book.

Comments powered by CComment