- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Andrew Fuhrmann reviews 'Young Eliot' by Robert Crawford

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

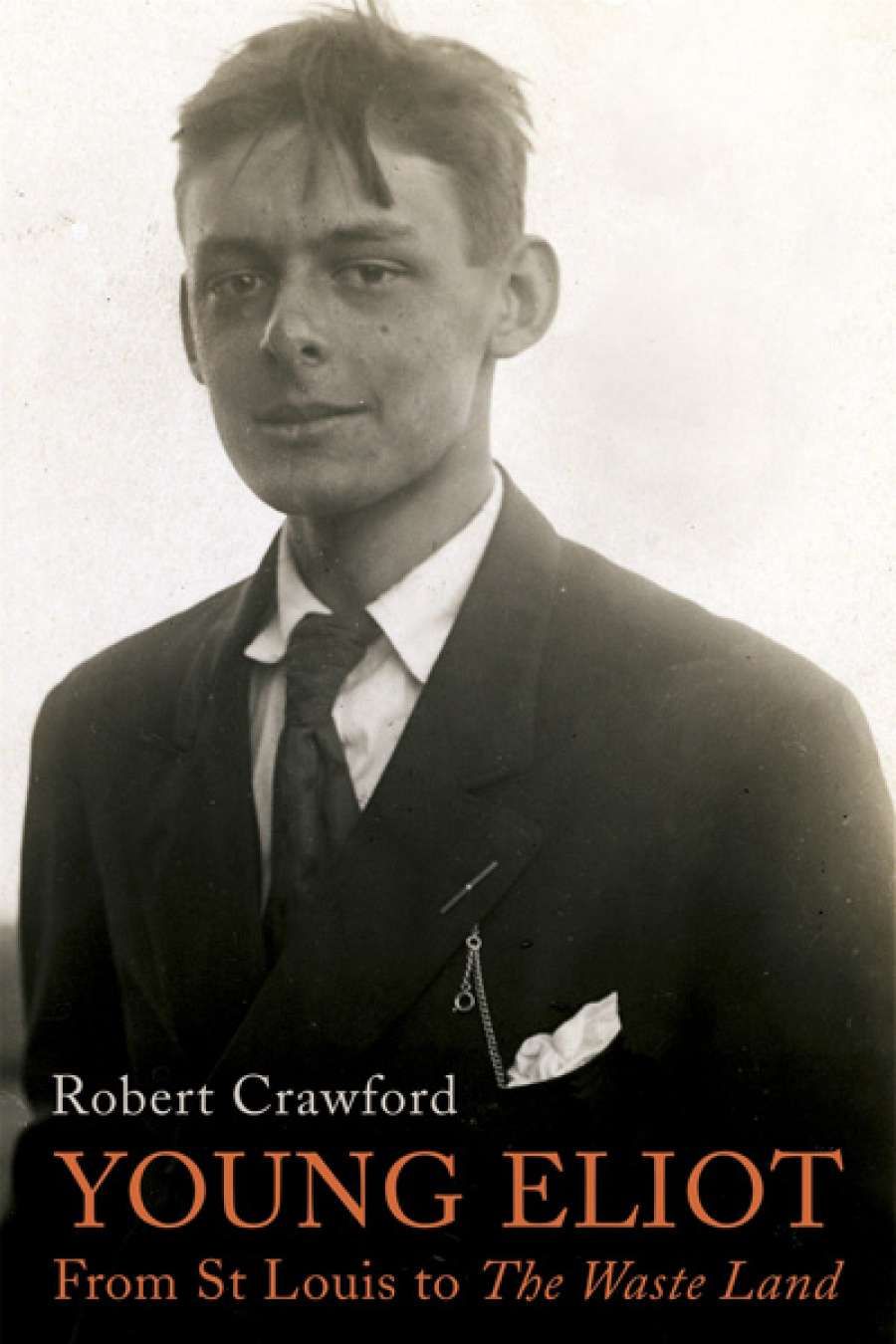

- Book 1 Title: Young Eliot

- Book 1 Subtitle: From St Louis to The Waste Land

- Book 1 Biblio: Jonathan Cape, $69.99 hb, 512 pp, 9780224093880

So the key event of volume one is Eliot's discovery of the French poet Jules Laforgue, whose free-verse representations of urban decay enabled Eliot to make poetry from his childhood experiences. As Eliot said, the encounter transformed him almost overnight 'from a bundle of second-hand sentiments into a person'.

Crawford, a poet himself, is particularly sensitive to the significant and obscure process by which the poet Eliot finds his voice:

Ultimately, Tom became a great poet through learning how to access and articulate unforgettably the wide spectrum of his inner life, his experience and his voracious reading. He learned to face up to and make poetry out of his own hurts, but gave his material a wider resonance through blending it with what he read.

After what he called his 'romantic year' in Paris, Eliot returned to Harvard for a doctorate in philosophy. He read Bergson in French, the Upanishads in Sanskrit, and Heraclitus in Greek, with German, Italian and Latin, the idealism of F.H. Bradley, the relativism of Norbert Wiener, Aristotle, and the sciences all thrown in. No other major twentieth-century poet, Crawford observes, was so thoroughly and strenuously educated.

At Harvard in 1913 he fell in love with Emily Hale. He tried to tell his love, but nothing came of it. They were young and no doubt confused. Eliot later confessed that in his twenties he was very immature and very timid. Hence the tension that Crawford attempts to delineate:

Here I am, an old man in a dry month,

Being read to by a boy, waiting for rain.

The old man and the boy. If Eliot was always Old Eliot, he was also always Young Eliot, a child excruciated with desire and feelings too deep for words to fathom. It was his second wife, Valerie, who said that there was 'a little boy' in Eliot who had never been released. His emotional isolation resounds in a letter to his Harvard friend, the poet Conrad Aiken: 'I should be better off, I sometimes think, if I had disposed of my virginity and shyness several years ago: and indeed I still think sometimes that it would be well to do so before marriage.'

'Crawford describes a world teeming with potential influences'

Enter Vivienne Haigh-Wood. Eliot met this vivacious young flirt of an Englishwoman while he was at Oxford. Crawford wallows less in the anguish of this catastrophic match than previous biographers. The marriage was impulsive, but not absurd. Vivienne shared many of Tom's interests and, backed by Ezra Pound, wholeheartedly encouraged his poetry, in which she passionately believed.

While not as wild about Viv as her biographer Carole Seymour-Jones, Crawford does show that Vivienne was a sensitive editor of Eliot's work who could give him a 'shove' when necessary. In some ways, she was just what he needed. And as they both pointed out, she did at least manage to keep him in England where his literary career blossomed.

T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf, June 1924 (photograph by Lady Ottoline Morrell, National Portrait Gallery, London, via Wikimedia Commons)

T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf, June 1924 (photograph by Lady Ottoline Morrell, National Portrait Gallery, London, via Wikimedia Commons)

There is much gossip and anecdotage about London's close-cobbled literary world. Crawford doesn't try to fit it all in, but we do meet Katherine Mansfield and the Woolfs, the brilliant Lytton Strachey, the pugnacious Wyndham Lewis – and of course Bertrand Russell, who invited the cash-strapped newlyweds to share his flat, then seduced the bride.

Meanwhile Eliot edited, lectured, reviewed, and made himself snug at Lloyds Bank. Then, from 1918, he contemplated a major poem, a sprawling survey of Tarot cards and Sanskrit scripture, fertility rites, and modern marriage agonies. But it took four years, a nervous collapse, a psychiatric cure in Lausanne, and the inspired editorial midwifery of Ezra Pound to finally bring off that always already ruined monument, The Waste Land. Eliot wondered if it wasn't a 'wholly insignificant grouse against life'; but Pound, who knew a classic when he saw one, declared himself 'wracked by the seven jealousies'. The poem will of course endure like Big Ben and Picasso.

'Crawford ... is particularly sensitive to the significant and obscure process by which the poet Eliot finds his voice'

Crawford handles the composition of The Waste Land, its borrowings and allusions, its obscurity and its manifest and mysterious passion, with tremendous poise. Moreover, he takes seriously, as few biographers do, the wisdom of Eliot's own critical injunction: 'It is not the "greatness", the intensity, of the emotions, the components, but the intensity of the artistic process, the pressure, so to speak, under which the fusion takes place, that counts.'

In Young Eliot, the richness of the detail makes for an immensely readable book, one in which life itself is apprehended as a transitory process, and its achievement nothing more nor less permanent than that ghostlike thing, a sensibility.

Comments powered by CComment