- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Custom Article Title: John Allison reviews 'My Life with Wagner' by Christian Thielemann

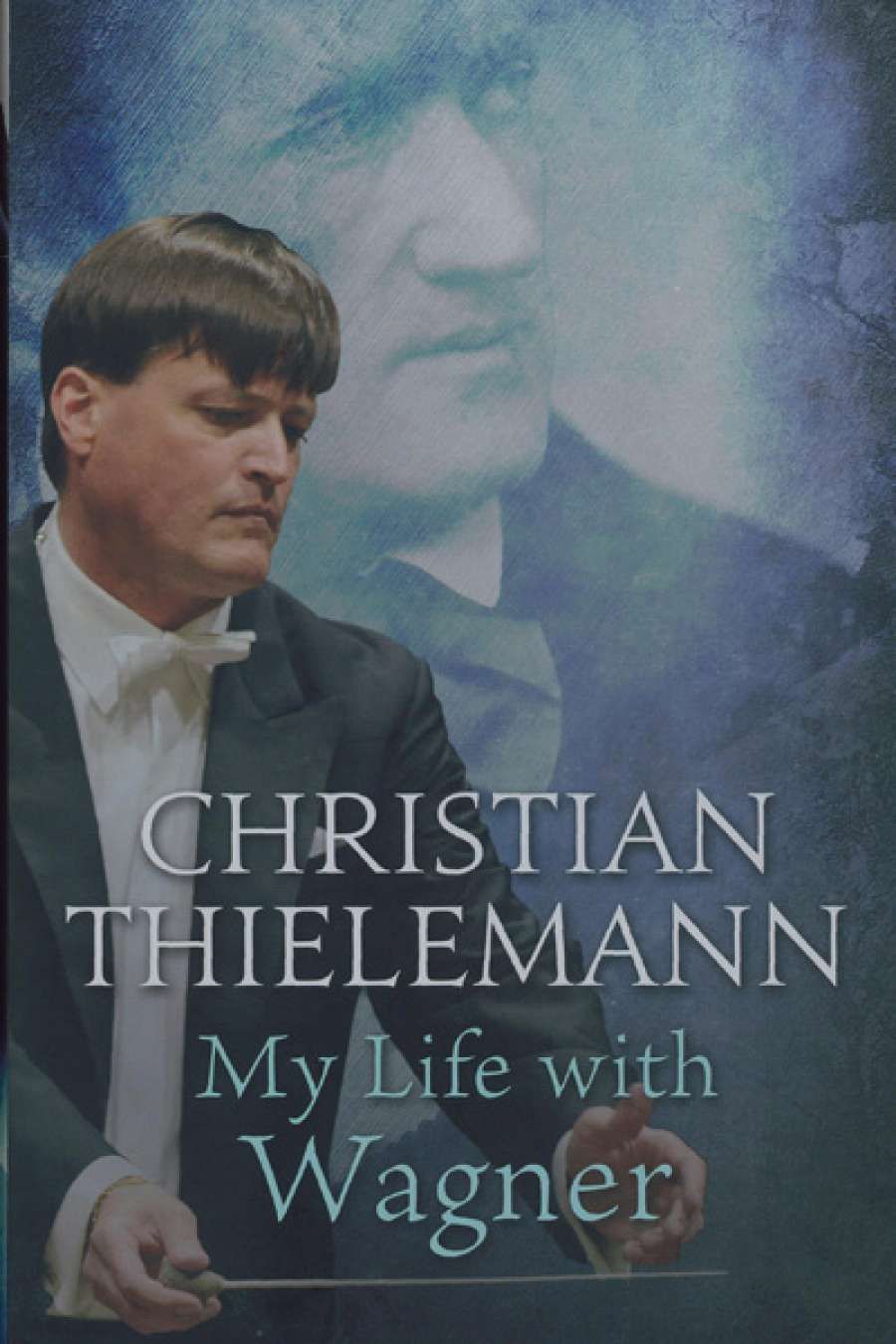

- Book 1 Title: My Life with Wagner

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $49.99 hb, 281 pp, 9780297608554

It is a deeply frustrating book, not without its valuable insights, as one would expect from someone with such close inside knowledge of Bayreuth. But the overall tone is uneven and naïve, in many places chatty in a contrived way, like fireside tales from a prematurely aged Onkel Christian (he turned fifty-six this year); it is likely that the translation (Anthea Bell) adds another distancing layer to a book that is surely substantially ghosted (by Christine Lemke-Matwey). Some of Thielemann's stories draw one in, and he is touching in his account of his early Berlin upbringing in what he calls a 'comfortable middle-class parental home' and about his teenage years, when he was consumed by the idea of becoming a conductor. He tells a sensible enough story about the long way up.

Christian Thielemann with Wolfgang Wagner on the stage of the Bayreuth Festival Theatre in 2002

Christian Thielemann with Wolfgang Wagner on the stage of the Bayreuth Festival Theatre in 2002

However, a statement in the Foreword's first paragraph already gives pause for thought, not because he compares Mahler unfavourably with Wagner – musical tastes are subjective, after all – but because his argument is weak. 'I had to decide between the more life-affirming or the more life-denying of the two,' he says, 'between Utopia and the enticement of the abyss, between Wagner and Mahler. I came down on the side of Wagner (and Bruckner).' For someone keen to stress his deep musical responses to everything – immersion in Wagner's music allowing him off the ideological hook, even if it goes against Wagner's concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk – Thielemann appears strangely deaf to the life-affirming pantheism that Wagner and Mahler share. There is a lot of nature-music in both composers, certainly more than in the stagnant pools of Bruckner, and how can one call the composer of that most magnificently morbid, necrophiliac masterpiece, Tristan und Isolde, 'life-affirming'?

Could it be that Mahler's Jewishness makes him uncomfortable? Although Thielemann puts up a spirited defence of Mendelssohn, saying some interesting things about this composer and almost apologising for the way he was treated first by Wagner and then by the Nazis, he ties himself in knots elsewhere. Thielemann has made no secret of his political conservatism and has relished many past controversies, yet he has always denied accusations of anti-Semitism. So the chapter on the ideology of Wagner and his notorious anti-Semitism is an area of this book that demands attention, yet Mein Kampf mit Wagner (as one wag of my acquaintance has nicknamed it) barely scratches the surface here.

'Could it be that Mahler's Jewishness makes him uncomfortable?'

For Thielemann, 'There is no room for [Wagner's anti-Semitism] in the music, where C major does indeed remain C major.' Fair enough, but that is no reason for virtually whitewashing that unrepentant old Nazi Winifred Wagner; Thielemann also gets a little sentimental about the unpalatable early opera Rienzi (whose manuscript is believed to have perished alongside Hitler in the Berlin bunker), but then he did make his full Wagnerian début conducting a concert performance of the work in Hanover in 1985. Recounting some entertaining coffee parties of his youth, he attempts the 'Some of my best friends are Jewish' line of defence, only to scupper his case by describing the fellow guests, one visiting from Wagner-starved Jerusalem, as 'amusing older ladies who ... had flowery names and read books backwards'.

Adolph Hitler in conversation with Winifred Wagner and Joseph Goebbels at the Bayreuth Festival Theatre, 23 July 1937

Adolph Hitler in conversation with Winifred Wagner and Joseph Goebbels at the Bayreuth Festival Theatre, 23 July 1937

By Thielemann's own admission, all that stood between him and Wolfgang Wagner was a taste (or not, in Thielemann's case) for sausage salad. His memories of Wolfgang (the composer's grandson, stage director, and boss of Bayreuth, who died in 2010) have the value of one who knew the man well, yet Thielemann conveniently overlooks most of the Bayreuth controversies, fails to question the festival's wider future, and supports the family's continuing hold on it. But those fascinated by Bayreuth minutiae will be rewarded by some backstage chat on matters from fee structure to the conductor's view of the uniquely terraced orchestra pit. Bayreuth-watchers will also enjoy snippets such as the Lars von Trier episode: Thielemann had a ringside seat, as it were, while the Danish film director dithered over whether or not to stage the Ring in 2006 (he eventually withdrew).

'Mein Kampf mit Wagner (as one wag of my acquaintance has nicknamed it) barely scratches the surface here'

Surprisingly superficial in his thumbnail sketches of those conductors whose portraits line the 'rogues' gallery' under the stage at Bayreuth, Thielemann is more interesting about certain other figures, not least Otmar Suitner (perhaps because he conducted Palestrina by Pfitzner – Thielemann's own unfashionable love for that controversial composer goes unmentioned). He describes him approvingly as a Kapellmeister, while acknowledging that the word is often used (at least in the English-speaking world) somewhat negatively. Thielemann apparently prefers to see himself as a Kapellmeister, too, offering leadership rather than dictatorship – no mention that he is known for being a bit autocratic and moody. He lightens up enough to say that 'operetta (like German comic opera, a shamefully neglected genre) is an excellent teacher of the Kapellmeister's craft'.

The third part – nearly half the pages – is given over to brief and basic introductions to each of Wagner's stage works, covering everything from plot summaries to recommended recordings. There are misprints and factual errors scattered throughout, and the book isn't helped by the literal translation of everything – no one talks about Wagner's early operas as The Fairies (Die Feen) or The Ban on Love (Das Liebesverbot), and 'the Comic Opera House of Berlin' is a confusing way of referring to that city's Komische Oper. The populist tone sits oddly with some of the subject matter, as if the book cannot decide at whom it is aimed, but perhaps that is symptomatic of a serious conductor who clearly craves the adoration of a wide public.

Comments powered by CComment