- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Nick Hordern reviews 'Frontline Ukraine' by Richard Sakwa

- Book 1 Title: Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands

- Book 1 Biblio: I.B.Taurus (Footprint), $51.95 hb, 297 pp, 9781784530648

To Russia, Ukraine is not just another neighbour. Kiev and Moscow have orbited around each other for centuries. Ukraine was the cradle of Russian Christianity, the scene of historic Russian victories, the birthplace of important Russian writers and politicians, a breadbasket and then the forcing-house of tsarist and Soviet industrialisation, particularly in the south-east, now the stronghold of the Russian-backed separatist rebels. Ukraine remains one of Russia's most significant economic partners. Taken altogether, it is of the highest importance to Russia.

None of this means that Russia is entitled to a free hand in Ukraine. But it does mean that Moscow has legitimate interests there, and will strive to protect them. Sakwa's argument is that Brussels and Washington should have taken this into account. Instead, in their dealings with Kiev they studiously ignored Moscow, and the Ukrainian crisis was the result.

'Sakwa's book is a salutary challenge to the very basis of Australian foreign policy: the principle that Washington is always right'

In November 2013, President Viktor Yanukovych – a veteran Blue politician, democratically elected, notoriously corrupt – was due to sign an Association Agreement (AA) with the EU, aimed at boosting trade and improving governance. Sakwa argues the AA would have precluded Ukraine joining Moscow's own proposed free trade zone and would have required Ukraine to align itself with European security and foreign policies. This in a climate in which EU foreign and security policy has increasingly become an extension of NATO.

Previously, in 2008, attempts by the then-Orange Ukrainian government to move towards NATO membership were blocked by internal and external opposition. Moscow made it clear that it would not tolerate Kiev joining an alliance whose fundamental rationale is, after all, anti-Russian. In Sakwa's view, in November 2013 the situation was repeated: the security implications of the AA made it not just an economic threat to Moscow, but a strategic threat as well. Adoption of the AA would have represented the triumph of the Orange camp, and the decisive defeat of the Blue. And of Russia.

Under pressure from Moscow, Yanukovych deferred signing the AA; in response Orange pro-Europe protestors set up camps in Kiev's Maidan square. Then Yanukovych accepted Moscow's counter-offer to the AA and the ranks of the Maidan protestors grew to include radical anti-Russian nationalists. The protest became the focus of opposition to Yanukovych, violence erupted, and numerous protesters and police were killed. In February 2014 Yanukovych fled to Russia.

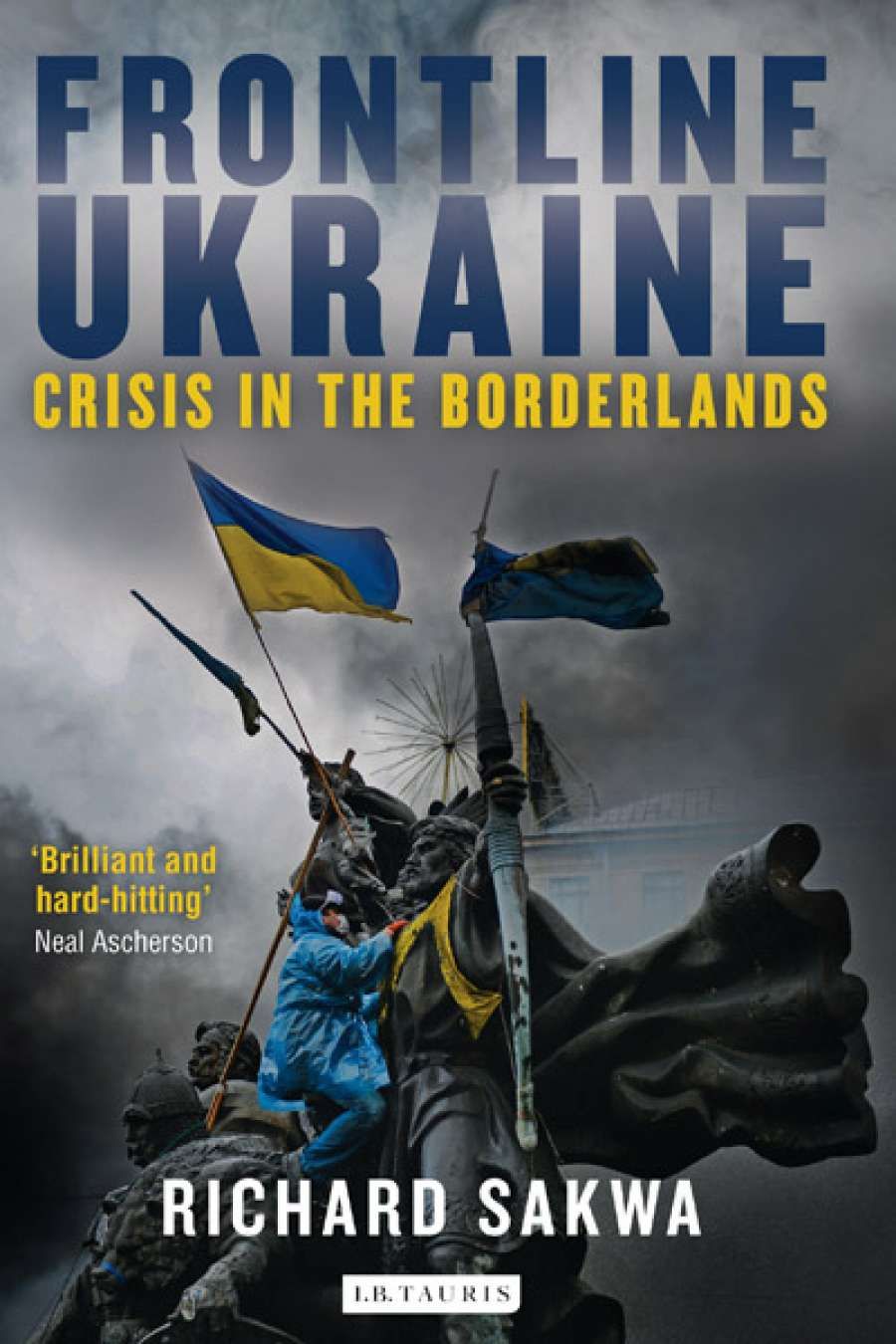

Anti-government protests in Maidan square, Kiev, December 2013 (photograph by Sasha Maksymenko via Wikimedia Commons)

Anti-government protests in Maidan square, Kiev, December 2013 (photograph by Sasha Maksymenko via Wikimedia Commons)

Next, Russian troops took control of Crimea. Russia first occupied Crimea in the eighteenth century (that is, before the British occupied Australia); it was transferred to Ukraine in 1954 but remained home to one of Moscow's most important military bases. In March 2014 a disputed referendum saw Crimea reintegrated into Russia. Soon afterwards, a separatist rebellion erupted in the Russian-speaking, coal and heavy industry region of Ukraine's south-east, the Donetsk and Lugansk regions. Russia provided the rebels with military support, including the SA-11 surface to air missile system that brought down MH17 in July 2014. Sakwa describes the shootdown as a 'dreadful mistake': 'No one had planned to shoot down a civilian airliner, just as the USS Vincennes had not deliberately shot down an Iranian airliner in 1988,' he says, referring to the notorious incident in the Persian Gulf.

'''No one had planned to shoot down a civilian airliner, just as the USS Vincennes had not deliberately shot down an Iranian airliner in 1988'''

Then in February 2015 a ceasefire ('Minsk II') was brokered, which stabilised the front line between the Ukrainian government troops and the Russian-backed separatists. Though routinely violated, the ceasefire holds – just. The prognosis is for a 'frozen' conflict, with Crimea, Donetsk, and Lugansk remaining under Russian control, Russia remaining under Western sanctions, and relations between Russia and the West going from worse to worse.

The great value of Sakwa's book is that it confronts the notion that only the United States and its allies have legitimate foreign policy interests and that any idea emanating from outside the US alliance system must be 'potentially divisive and dangerous'. It shows just how poorly the triumphalism following the end of the Cold War has served the United States and its allies, imbuing them with a contempt for the Russian 'losers' – to the point where the former Australian prime minister felt safe (from behind American skirts) making schoolyard threats to 'shirtfront' the president of Russia.

In a hotly contested debate like this there is no middle ground: as Sakwa acknowledges, his book 'will undoubtedly rile many'. But there is another side to the Ukraine story, and Sakwa tells it. Loyal US ally Australia may be – but we could at least listen.

Comments powered by CComment