- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Billy Griffiths reviews 'Comrade Ambassador' by Stephen FitzGerald

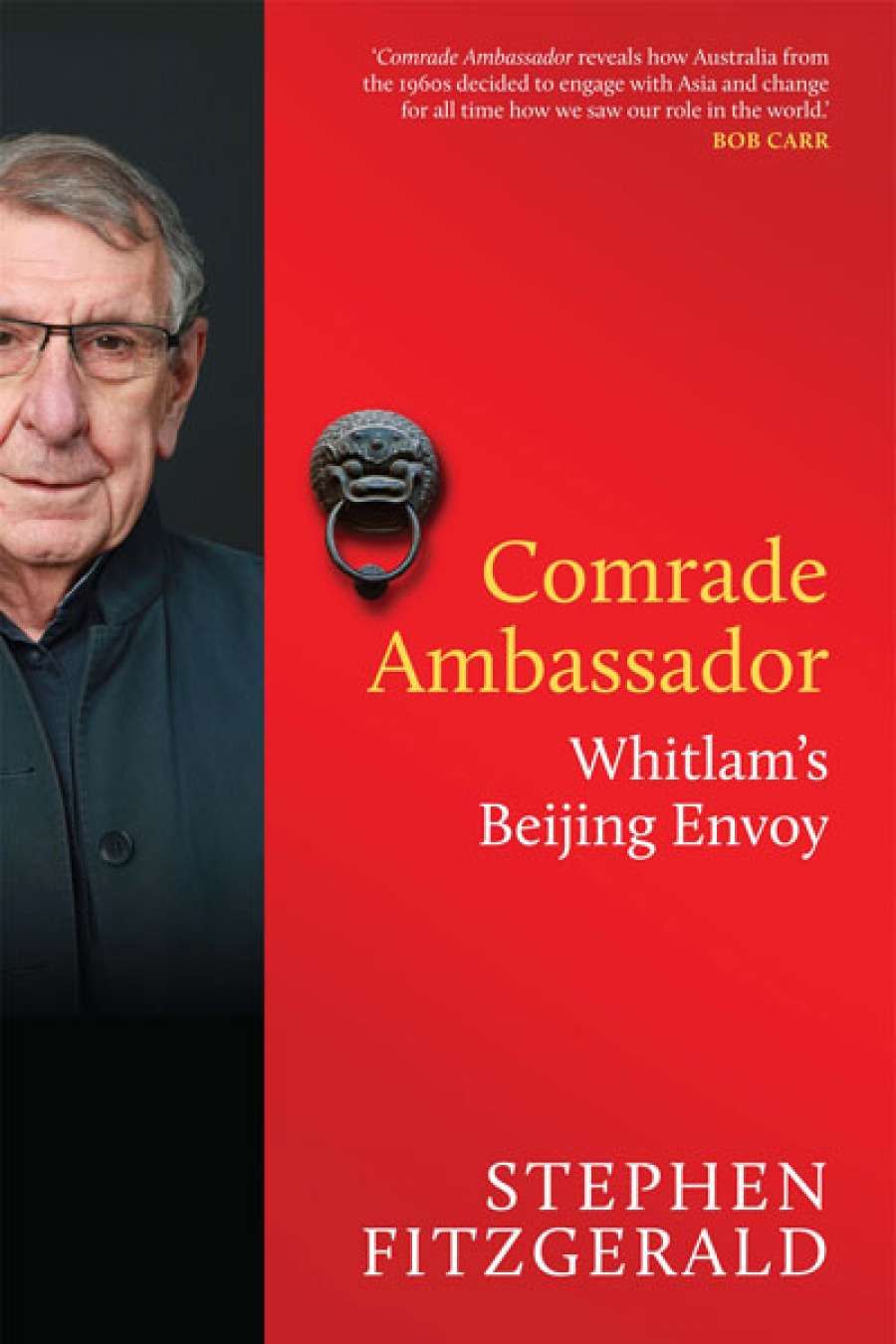

- Book 1 Title: Comrade Ambassador

- Book 1 Subtitle: Whitlam's Beijing Envoy

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $34.99 pb, 272 pp. 9780522868685

The book is written in the present tense, which gives his prose a refreshing immediacy. FitzGerald is alert to the sounds and smells and tastes of China, and writes evocatively of Chinese food, both the wonderful and the bizarre. This is a culinary, as much as cultural, adventure. The chapters are suffused with a gentle humour and are punctuated with anecdotes, refined from years of telling. But there is a hard edge to these sensuous details. FitzGerald is presenting the China he has come to know: a culture, a place, and a people; not the abstraction that is bandied about in public discourse – 'China wants'; or 'the Chinese think'. 'It's the relationship with the unabstracted that has borne us successfully for more than forty years, and it's that which must bear us through the next forty, not a calculation of profit or loss.'

FitzGerald grew up in Hobart in the 1930s and 1940s and did not meet an Asian person until he studied at the University of Tasmania in 1957. 'What we ate in Hobart expressed our cultural heritage, and insularity.' After taking the job as a junior diplomat, he was sent to learn Mandarin in Cantonese-speaking Hong Kong and was thrust into a world of intrigue: 'You have to assume some of your best friends are spies. Later I discovered some were.' In the late 1960s he left the Department of External Affairs in protest over Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War and what he regarded as an 'illogical, delusional, and unsustainable' policy towards China. It was as an outsider – an academic, not a diplomat – that he first encountered Gough Whitlam. The two men bonded over food and a shared foreign policy vision. He describes Whitlam's breaking of the political embargo on relations with China as 'the central and symbolic beginning of Australia's coming to terms with [Asia]'.

'He became one of the key players in Australia's relations with Asia, working as Australia's first ambassador to China under Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser'

FitzGerald's relationship with Whitlam, their audacious visit to China in 1971, and his time serving as 'Whitlam's Beijing envoy', forms the core of the book. In 1973 all the Australians in China could fit around his Christmas table. He likens the process of establishing an embassy in Beijing to 'putting together the nerves and veins and arteries of a severed limb'. He describes his shock at news of the Dismissal and the gradual admiration he formed for the new prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, who consolidated Australia's reorientation towards Asia.

After turning down a diplomatic posting to Japan and briefly considering entering politics, FitzGerald began a career as a business consultant in China (or, as he describes his role, 'general performing bear'). He was an adviser to the Hawke government on immigration – an exhilarating and frustrating experience – and he offers rich vignettes of later prime ministers and their relationships with China: Keating was 'intense, but also intensely interested in Asia'; Howard's 'Asia scepticism' dealt a near-mortal blow to Asian languages in Australia; Rudd was inscrutable, moving in and out of China policy discussions 'like a Cheshire Cat'; Gillard acted like 'an innocent abroad in foreign affairs'; while Abbott's diplomacy was dangerously directed towards 'a domestic grandstand'.

'Abbott's diplomacy was dangerously directed towards ''a domestic grandstand'''

In the final pages of Comrade Ambassador, FitzGerald draws these insights together in a fiery critique of the culture of policy-making and leadership in Australia today. Independent foreign policy, he laments, has been replaced by 'ad hoc decisions and thought bubbles', 'breaches of international conventions', and 'the subordination of Australian strategic thinking to US interests'. He hopes, with less optimism than he once had, for ideas and vision to return to public debate: for Australian foreign policy to be shaped once more by courageous and Asia-literate leaders.

The change in Australia's outlook on Asia during FitzGerald's lifetime has been dramatic, profound, and enriching. China has ceased to be the mysterious other of his childhood and is now very much a part of our daily lives. We are fortunate to have such a thoughtful and engaging insider account of this transformative period of Australian history.

Comments powered by CComment