- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Kevin Rabalais reviews 'Scorper' by Rob Magnuson Smith

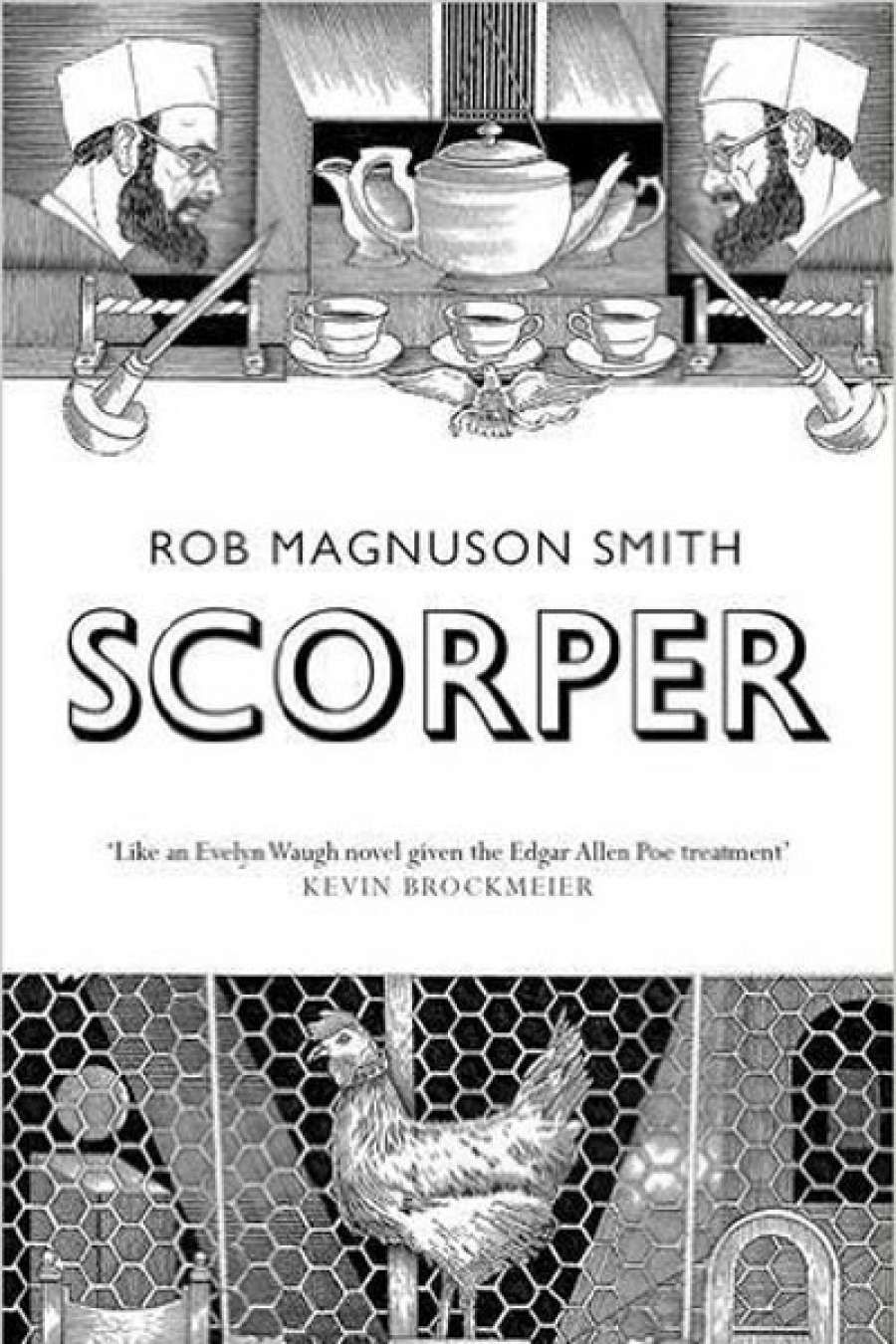

- Book 1 Title: Scorper

- Book 1 Biblio: Granta Books, $19.99 pb, 263 pp, 9781783781065

First person and third, these two obvious perspectives, dominate storytelling. Yet the way a writer relays a story, much like the details she uses to enrich it, should never be commonplace. That's why a novel like Jay McInerney's Bright Lights, Big City (1984) – one of the most famous and best examples of a second-person narrative – woke a generation from its reading slumber. On the other hand, bad examples of second-person point of view in literary fiction fall upon our ears like dissonant chords. Another danger is that the narrative will progress in a this-happened-next manner better suited to genre fiction. In the best examples, however, the voice rises from the page obvious and essential, as it does in Rob Magnuson Smith's Scorper, the delightful and entertaining – and often laugh-out-loud funny – new novel by the author of The Gravedigger (2010) and recipient of the 2015 ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize.

Magnuson Smith proves himself a gambler from the outset. He plants the seeds of this quiet yet complex novel in his first paragraph:

You're on your way to Ditchling. It's a Thursday afternoon in late March during the unfortunate year of 2012, the year the bookshops are closing and the libraries are downsizing and the Internet attempts its final stranglehold on the written word. You're an American. You're on vacation in the land of your English ancestors. The US economy teeters on the edge of another recession, and you'd better be back at work in a couple of weeks or you'll lose your job.

'In much contemporary fiction, point of view works like wallpaper to which we grow accustomed, usually within the first paragraph'

Rather than used to address the reader directly, Magnuson Smith's second-person perspective emphasises the psychological distance that the narrator inhabits from himself. 'Moments pass,' as he writes, 'the moments of a man who has become lost to himself.' While our guide through Bright Lights, Big City remains anonymous, Magnuson Smith grants his narrator a name, John Cull, and an intricate ancestry.

For ten years, Cull has worked as a copy editor of print ads. His grandfather, also named John Cull, had lived in Ditchling as a scorper, a craftsman who uses an engraving device of the same name. The narrator arrives in the Sussex village to discover that his grandfather had written a book, also titled Scorper, about his apprenticeship with the real-life artist Eric Gill. Cull reads Scorper and mingles with the natives. He chisels back the layers of the past, finding romance and drama along the way in this novel that moves with ease from humour to introspection. All the while, Cull strives, ultimately, to 'inhabit the "I" that you've concealed for too long – the "I" belonging to your true inner-voice'.

Rob Magnuson Smith

Rob Magnuson Smith

The demands of a second-person perspective work best in the sprint. One exemplary case, Carlos Fuentes's Aura runs only sixty pages; McInerney's novel elapses in fewer than 200. Magnuson Smith attempts something longer here, a commendable ambition that at times taxes the reader. In the same way that an overuse of the first-person pronoun can propel a personal essay into vanity, Scorper at times adopts the tone of a choose your own adventure novel: 'You jiggle the handle. The door opens abruptly, and a sickly woman with long white hair stands in front of you in a white nightgown.' Magnuson Smith prevents this from going on for too long, however, with a late shift in the narrative.

Too often we hesitate to accept, much less embrace, work that attempts to extend the dialogue of an art form. This may be why publishers use the word 'quiet' to describe literary fiction that lacks an explosion or murder in the opening paragraphs. Scorper succeeds as a quiet novel in the best sense. In its sincere attempt to understand the past and the world we inhabit, it juggles the traditional with the experimental. Well-conceived and executed with a masterly vision, Magnuson Smith's novel unfolds in a manner that eliminates the possibility of any other strategy. He delivers his necessary narrative with conviction.

Comments powered by CComment