- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

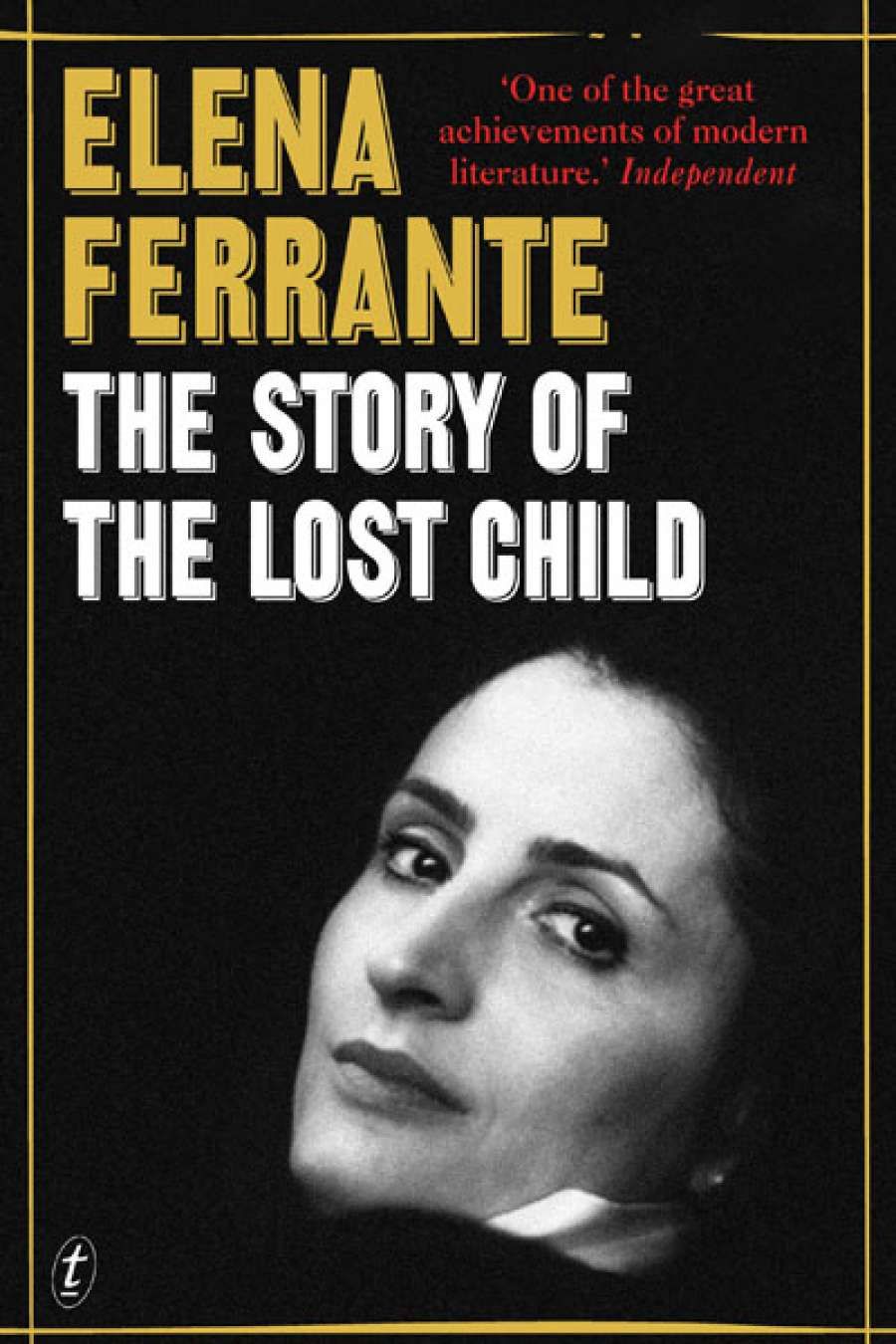

- Custom Article Title: Luke Horton reviews 'The Story of the Lost Child' by Elena Ferrante

- Book 1 Title: The Story of the Lost Child

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 473 pp, 9781925240511

Ferrante's subject is the lifelong friendship between Elena ('Lenù') Greco and her brilliant and infuriatingly taciturn friend Raffaella ('Lila') Cerullo, two young women born in a bitterly poor part of Naples towards the end of World War II. Life in 'the neighbourhood' is hard for everyone. It is a community cowed by the Camorra. For the daughters of a porter and a shoemaker, life will be circumscribed and severe. Still, the social changes taking place across the Western world in the 1950s and 1960s are felt, and Lenù's story, in the first volumes, is one of an intellectual and feminist awakening made possible by her own precocity and the influence of a few key figures, mainly female teachers, who see the potential for a life for Lenù and Lila beyond marriage and motherhood.

The luminously beautiful Lila suffers from a dissociative disorder she describes as 'dissolving boundaries', where everything solid loses its shape before her eyes. This condition is the central metaphor of the novel. In the unceasing tumult that is their lives, there are dissolving boundaries everywhere. Lenù's ambition dissolves, at least for herself, the class and gender bound-aries that confine most women in the neighbourhood. Her evolving feminist consciousness means that marriage and motherhood do not mark boundaries that cannot be dissolved and redrawn either. Elsewhere, gender and identity lines are blurred in other ways when their childhood friend Alfonso becomes the first transgender person in the area and eerily refashions himself in Lila's image. Each of these transgressions involve great struggle, but the most painfully unreliable boundary, at least for Lenù, is that between her and her all-consuming friend.

'Over the last year, Italian enigma Elena Ferrante has become one of the most passionately advocated literary sensations of our time'

At the end of the previous instalment, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (Storia di chi fugge e di chi resta, 2013), it seemed that through her work and her love for Nino Sarratore, Lenù might have finally shaken off Lila's largely corrosive influence. But as The Story of the Lost Child takes up the narrative thread, at the exhilarating moment when Lenù and Nino rush off to Montpellier to be together, tellingly it is the status of Lenù's relationship with Lila that needs to be established first. This remains the story that is being told. And as a result, the pervading sense of this last instalment remains one of unease.

It is Lila more than anyone else who threatens Lenù's own identity, her own will. No matter how much Lenù achieves, she never quite escapes the feeling that Lila might eclipse her. Even in her sixties, after a long successful career as a writer, she worries that Lila might be working on something that would make her many novels meaningless by comparison. Lila remains for Lenù the girl who is smarter, more talented, and more powerful than her. She also remains the terrible force that can shatter an opponent with a single, well-aimed remark.

'The most painfully unreliable boundary, at least for Lenù, is that between her and her all-consuming friend'

The struggle to balance her own life with the life of her friend troubles Lenù throughout the telling of this story. It is an anxiety that is directly addressed in The Story of the Lost Child: 'I either tend to pass over my own affairs to recapture Lila and all the complications she brings or, worse, I let myself be carried away by the events of my life, only because it's easier to write them.' For her part, Lila claims to want to be kept out of Lenù's work. She considers herself an unworthy subject: 'Forget it, Lenù. One doesn't tell the story of an erasure.' And while Lenù does not trust Lila's words she does not trust her own impulses either. The whole cycle is structured around this insecurity. At one point, Lenù even wonders if this book might have been Lila's true intention all along. This monument to their lives, to their friendship, might be what Lila had been pushing her towards, through all her disparagement of Lenù's previous work.

Either way, Lenù is ultimately driven by the conviction that their story, which as children they had vowed to write together, is worth telling; that this bitter and beautiful, pernicious and sustaining, female relationship is not a 'scribble on a scribble' as Lila describes herself, but instead the richest material, capable of filling quite easily the pages of four 400-page novels, or a single 1,700-page one.

Comments powered by CComment