- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Russia

- Custom Article Title: Mark Edele reviews 'Stalin, Volume I' by Stephen Kotkin and 'Stalin' by Oleg V. Khlevniuk

- Book 1 Title: Stalin, Volume I

- Book 1 Subtitle: paradoxes of power, 1878-1928

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $59.99 hb, 963 pp, 9780713999440

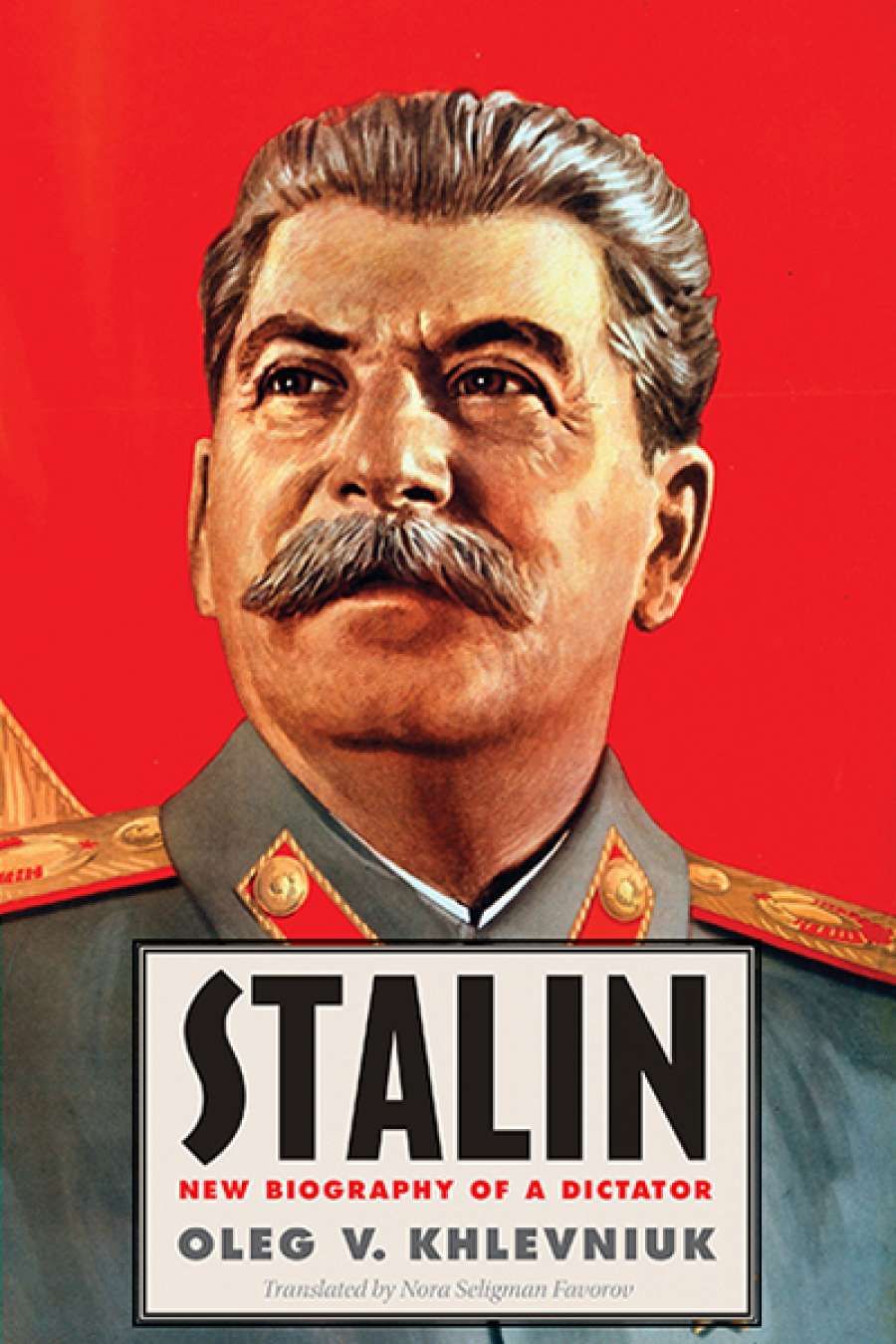

- Book 2 Title: Stalin

- Book 2 Subtitle: new biography of a dictator

- Book 2 Biblio: Yale University Press (Footprint), $71 hb, 408 pp, 9780300163889

Kotkin's Paradoxes of Power is only the first tome in a planned trilogy on the dictator's life. Despite its 739 pages of text (excluding endnotes, bibliography, illustrations, and index), Kotkin gets only to 1928, the year when the Stalin faction had finally established undisputed control over the Soviet government. The first volume thus ends before the momentous events which would shape Stalin's legacy: forced collectivisation of agriculture, crash industrialisation, and famine in the early 1930s; the Great Terror in the middle of the decade; expansion into Eastern Europe at its end, followed by what is still remembered as the 'Great Patriotic War' against the German aggressors of 1941–45; the postwar establishment of superpower status and renewed repression, this time of intellectuals and Jews. Moreover, for the first 408 pages, covering the years 1878 to 1922, the reader learns little about the man who would become one of the quintessential dictators of the twentieth century.

Instead, Kotkin provides a brilliant synthetic overview of Russian and early Soviet political history, interwoven with a no less expansive history of the world. Kotkin sure-footedly winds his path between opposing interpretations, writing with style, panache, a good eye for detail and drama, carefully dosed sarcasm, and well-placed counterfactual reflections. Readers interested in a well-written history of modernising and revolutionary Russia, which integrates domestic and international perspectives, will enjoy these first 400 pages. Those who want to learn more about the young Stalin are better served by Simon Sebag Montefiore's Young Stalin (2007), or indeed by Khlevniuk's succinct rendering of the youth of the later dictator.

This is the first known photograph of Stalin

This is the first known photograph of Stalin

Kotkin makes three observations about Stalin, once world history allows him to. First, he was a man of ideas (the wrong ones, Kotkin stresses: Marxism and Socialism, rather than capitalism and the market). He was a Marxist and a revolutionary socialist, and his ideology mattered to the decisions he would make. Second, he was a central actor in the Bolshevik party from at least the Revolution of 1917, and a faithful disciple of Lenin. This line of argument is directed against the influential rendering of Stalin's life by Leon Trotsky, one of the losers in the factional fights of the 1920s. These two points are well taken, but Robert Service in his 2005 biography has made them before. Indeed, as Khlevniuk points out, 'there is more agreement than controversy on the historical and ideational antecedents that shaped him [Stalin], including traditional Russian authoritarianism and imperialism, European revolutionary traditions, and Leninist Bolshevism'.

'Both are political books, but the politics are as different as the personalities of the authors'

What is new is Kotkin's third point: that Stalin's personality was formed by politics, in particular by the 'paradoxes of power', both of the Russian Revolution and of Stalin's personal dictatorship taking shape within it. On the one hand, Stalin the general secretary had nearly total power; on the other hand, his position was threatened again and again by a 'testament,' attributed to Lenin (who had died in 1924), which called for his removal. The bitter political fights of the 1920s, speculates Kotkin, left a deep imprint on the dictator's personality, which became marked by 'hyper-suspiciousness bordering on paranoia'. This pathology was further aggravated by 'the Bolshevik revolution's in-built structural paranoia, the predicament of a communist regime in an overwhelmingly capitalist world, surrounded by, penetrated by enemies'. This interpretation is plausibly rendered in the second half of the book. Stalin, it shows, was 'a victor with a grudge'.

I found myself mostly agreeing with Kotkin's account. This lack of discord is remarkable, given that I am part of a rival cohort of scholars of Soviet history, trained in the 1990s and early 2000s at the University of Chicago, and primarily supervised by Sheila Fitzpatrick (now University of Sydney), who has recently published her own take on Soviet high politics: On Stalin's Team: The Years of Living Dangerously in Soviet Politics (2015). By the logic of scholarly competition, historiographical factionalism, and academic loyalty, any member of this 'Chicago School' should be inclined to disagree with Kotkin's narrative. But I did not, because Kotkin transcends factional squabbles in truly masterly fashion – until page 723.

Tsarist police mug shots of Stalin, Baku, March 30, 1910.

Tsarist police mug shots of Stalin, Baku, March 30, 1910.

Then, in the conclusion, the professor lost his temper. At stake is the following question: why, once his team had decisively won political supremacy at the end of the decade, did Stalin abandon his support for the tactical compromises of the 1920s? Instead of continuing to allow small-scale farming and limited market relations (the so-called 'New Economic Policy', or NEP), he embarked on the disastrous policy of forced collectivisation and force-paced industrialisation. This is a long-standing debate, and historians have stressed structural factors, Stalin's personality, and ideological conviction as parts of the puzzle. After all the complexity and subtlety Kotkin displayed for hundreds of pages, I expected an intelligent synthesis here, too. Instead, we get the party line of the school he helped to form: Stalin was a convinced Marxist, a revolutionary who thought in class categories and hated market forces; hence the turn against NEP.

'Then, in the conclusion, the professor lost his temper'

Historians who say anything else are 'dead wrong', ignore 'the vast trove of evidence on the salience of ideology', or 'have it exactly backwards'. Really? Stalin the Marxist earlier supported the NEP, on similarly Marxist grounds, as indeed Kotkin demonstrates. He also shows that among Bolsheviks there were people who, despite their ideology, continued to support market mechanisms. Unlike Stalin, these Marxists were able to distinguish between successful farmers and 'class enemies'. Finally, and contradictorily, Kotkin argues on the final page of his book that had Stalin died, forced collectivisation would not have gone ahead – despite the incontrovertible fact that even without Stalin the country would have been run by Bolsheviks steeped in Marxist revolutionary thought. Ideology, then, explains both everything and nothing.

What raised Kotkin's blood pressure was a highly technical article by a young scholar of the Chicago school, published in a journal relevant only to historians of Russia. Oscar Sanchez-Sibony (whose first book, Red Globalization, was published by Cambridge University Press in 2014) argued that rather than only in the fight for power, the ideological struggles of the 1930s should also be contextualised in the 'very real and thorny economic crisis that confronted the Bolsheviks' (Kritika, 2014: 33). In principle, this interpretation should be compatible with Kotkin's otherwise contextualised reading of the political choices of the Bolsheviks in their international context, which quite obviously included the stuttering world economy on which the NEP depended. Instead, this interpretation became a 'pernicious idea', maybe because this very well-reasoned piece came from a rival school, maybe because assistant professors are not meant to challenge the ideas of Princeton chairs, or maybe because to Kotkin the argument smacked of Marxism (a bad thing, as everybody knows). Ideology, and only ideology, explains the end of NEP to Kotkin.

A rare family get together in the mid-1930s. Left to right: Stalin's son Vasily, Leningrad party boss Andrei Zhdanov, daughter Svetlana, Stalin, and Stalin's son (by his first wife) Yakov, who was killed in a Nazi POW camp.

A rare family get together in the mid-1930s. Left to right: Stalin's son Vasily, Leningrad party boss Andrei Zhdanov, daughter Svetlana, Stalin, and Stalin's son (by his first wife) Yakov, who was killed in a Nazi POW camp.

Khlevniuk, by contrast, provides a contextual explanation, combining politics and economics. The severe factional fights after Lenin's death, he argues convincingly, distracted the Bolshevik leadership from the economic problems of NEP. In the heated atmosphere of back-stabbing leadership struggle, the politicians found no time to actually attend to the necessary ongoing re-calibration of the policy. They let things run on their own, which meant they ran poorly. By the time Stalin's faction had won, it was too late to fix anything incrementally. The only alternative to the now clearly dysfunctional NEP was some kind of revolutionary aggression. Such a course of action agreed with Stalin and his men, who had learned their politics and their economics in the context of the Russian civil war.

'Khlevniuk has bigger fish to fry than assistant professors not knowing their place'

Khlevniuk has bigger fish to fry than assistant professors not knowing their place. In Putin's increasingly authoritarian country, a strange kind of neo-Stalinism has taken root, which sees the victory over Nazi Germany as ultimately excusing all the terror as 'historically necessary'. Its corollary is the praise of a strong state, a disregard for civil liberties, and an aggressive foreign policy.

Khlevniuk's weapon against this threat is careful argument, mastery of sources, and reconstruction of fact. He has no ambitions to use the vehicle of biography to rewrite not only the history of Russia but also the history of the modern world. He was asked to write a biography of Stalin. He wrote a biography of Stalin. And he wrote it in one volume, because he knows 'how it feels to gaze wistfully at stacks of fat tomes that will never be conquered'. The result of this restraint is a historiographical and literary masterpiece, which undoubtedly will remain the standard biography of Stalin for decades to come.

Comments powered by CComment