- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

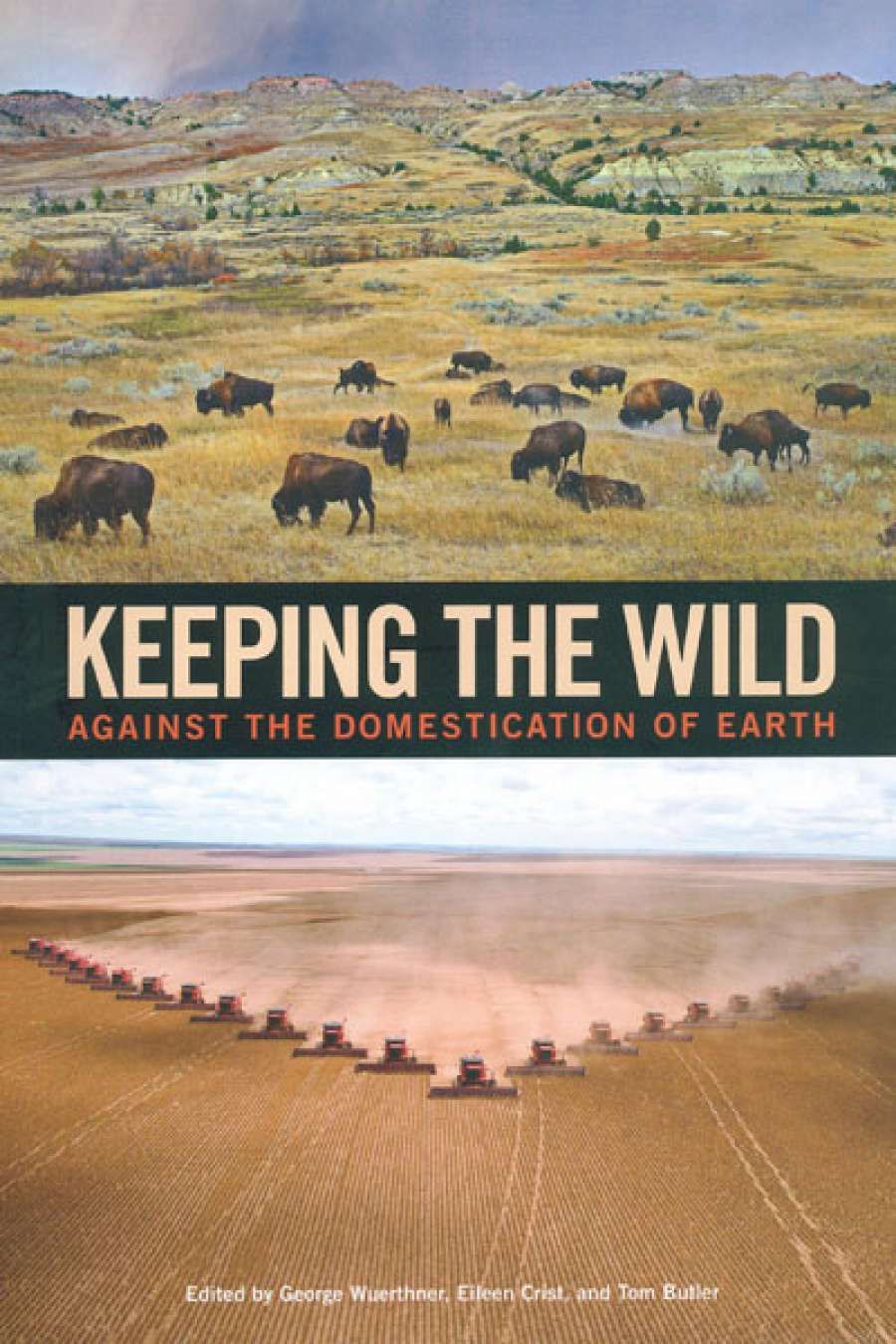

- Custom Article Title: Cameron Muir reviews 'Keeping the Wild' edited by George Wuerthner, Eileen Crist, and Tom Butler

- Book 1 Title: Keeping the Wild

- Book 1 Subtitle: Against the domestication of earth

- Book 1 Biblio: Island Press, $35 pb, 287 pp, 9781610915588

Earth scientists posit that the activities of some groups of people have caused so much environmental degradation and change that we are leaving the comfort zone of the Holocene. We are changing the chemistry of the atmosphere and acidifying the oceans; agriculture has destroyed vast areas of habitat. A third of the earth’s terrestrial productivity is devoted to human use. Our impact is so extensive it will be discernible in the fossil record. Hence, a new geological epoch – the Anthropocene (or Age of Humans).

Well-known activists, writers, and scientists in Keeping the Wild condemn ‘new conservation’ and reject the idea of the Anthropocene. It is an idea, according to the editors, that is being used to justify human dominion over the planet, a project to turn the world’s living systems into an engineered, homogenous ‘garden’ managed by technocrats. The main targets for criticism are Peter Kareiva, chief scientist at The Nature Conservancy, as well as Michelle Marvier of Santa Clara University and science writer Emma Marris. In 2012, Kareiva and Marvier published a paper criticising the legacy of Michael Soulé, a foundational figure in conservation biology and passionate supporter of an eco-centric basis for the field. The best way to get governments and industry to listen these days, argued Kareiva and Marvier, was to make human welfare the centre of environmental policies. According to Kareiva, the Anthropocene presents an ‘opportunity’ to shape the earth for our needs.

Contributors touch on the anthropocentrism of Western thought, the way in which language mediates our relationships with the rest of nature, the need to acknowledge emotions in decision-making, and the moral and scientific importance of ‘the wild’. Michael Soulé reflects on the entanglements between personal beliefs and science when he recalls the time he scurried to save hundreds of leatherback turtle eggs from being washed away by a swollen river that had cut through a beach. The sole Australian voice, Brendan Mackey, acknowledges the Anthropocene as an ‘empirical fact’ and makes the point that it demonstrates the end of human exceptionalism; that, like all other species, we cannot live outside ecological boundaries. Postscript pieces by Terry Tempest Williams and Kathleen Dean More provide eloquent first-person reflections on humility and loss. Most pieces in this volume, however, are partisan attacks on Kareiva and the concept of Anthropocene.

‘Well-known activists, writers, and scientists in Keeping the Wild condemn ‘‘new conservation’’’

The book has its origins in a meeting to determine a response to Kareiva. One can imagine the urgent sharing of ideas and outrage among like minds. There doesn’t seem to have been much effort to build on this. Instead, it can read like a think tank’s policy briefing. A diversity of perspectives would have made this a more compelling anthology. Individually these pieces would have worked well as Op-Ed pieces. Collected here, the uniformity and repetitiousness of arguments becomes wearing.

Peter Kareiva

Peter Kareiva

The blurb declares that the writers in Keeping the Wild ‘come out with rhetorical fists swinging’. Kareiva might have set the tone with his polemical manner, his oversimplification of traditional conservation, but here the intellectual and literary heft of this group of writers ends up underutilised, or misdirected. The debate is framed as an absolute binary. You either subscribe to the moral framework based on wilderness, in which pre-agricultural and Amish societies are offered as acceptable levels of human intrusion into the environment, or you are the enemy. This ‘you’re with us or against us’ attitude reduces future possibilities for the environmental and conservation movements. It overlooks decades of work towards healing the tensions between conservation and social justice. The neo-liberal turn in environmentalism warrants critical attention, but the analysis requires more nuance.

Before reading this book, I regarded people striving for better environmental and human relationships as a diverse collective. Now I would probably be disavowed. The moral of this book is that it’s only wild places that deserve our care.

Curt Meine offers one of the sagest contributions to Keeping the Wild. He writes, ‘vulnerability and toughness, fragility and resilience, turn out to be not opposing but interwoven qualities of ecosystems. But one needs history and perspective to make sense of these terms.’ It is the most sensible advice in the book, and Meine’s co-contributors could learn as much from it as the ‘new conservationists’.

Comments powered by CComment