- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Shannon Burns reviews 'Something for the Pain' by Gerald Murnane

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

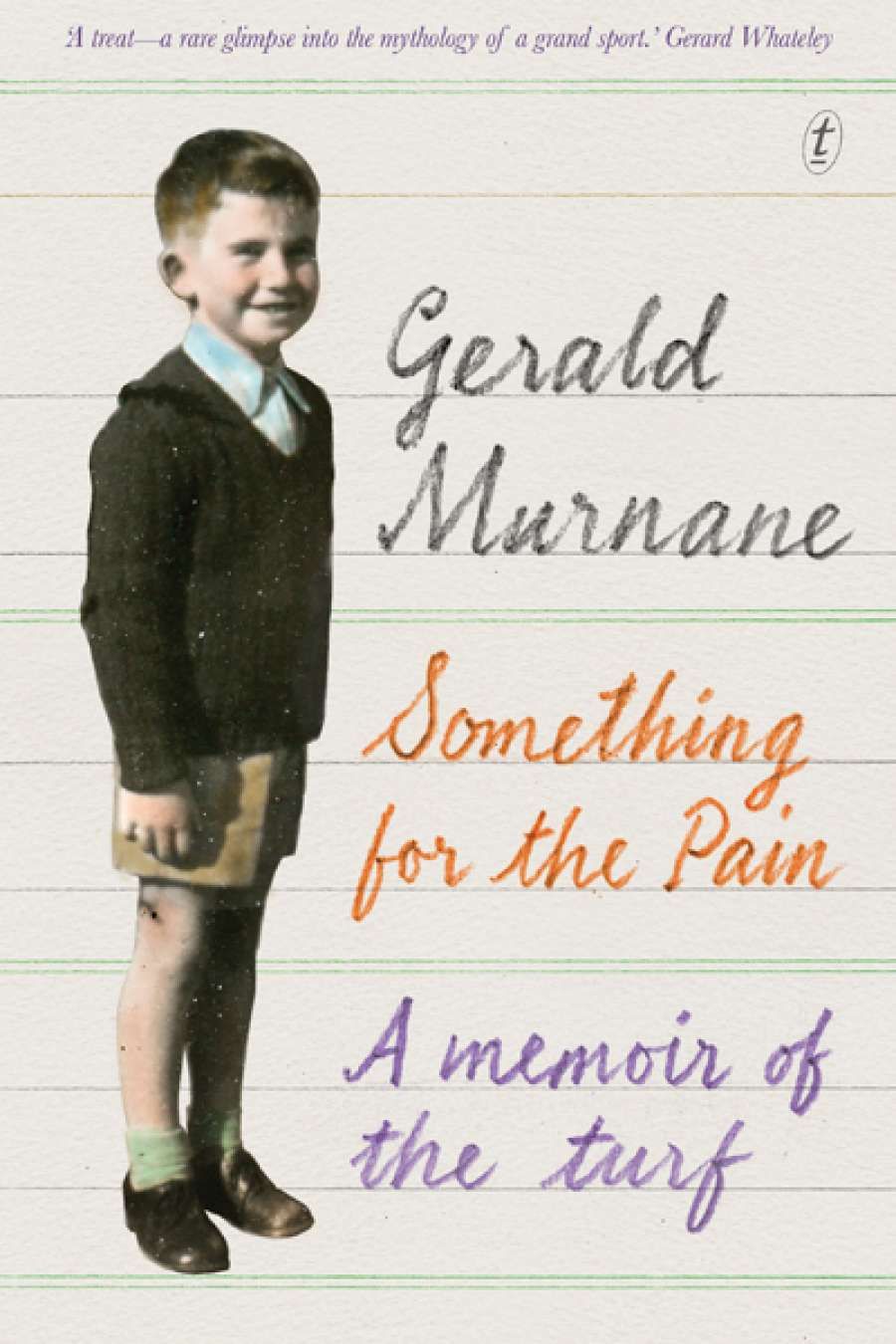

- Book 1 Title: Something for the Pain

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir of the turf

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 288 pp, 9781925240375

Murnane further enlarges our sense of racing’s possible influence on his fiction in his memoir. For example, we learn that he favours Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture over Beethoven’s string quartets or Bach’s fugues because ‘the overture, from its beginning to its end, brings to my mind a series of images comprising a complete narrative: a story beginning in the early morning and culminating in late afternoon; the story of a notable and closely contested horse race’. Murnane claims that the shape and pattern of a race embodies his preferred artistic form.

The best parts of Something for the Pain focus on seemingly marginal aspects of the sport. On the subject of racing colours, for example, Murnane writes:

I am someone for whom each shade or colour has a rudimentary quality of the sort attributed to persons while combinations of colours bring me hints of personalities … For me, each colour or combination of colours asserts something. To put it simply: for as long as I can remember, I’ve believed that colours are trying to tell me something.

He connects this sensitivity to colour combinations with synaesthesia, then talks about his quest for the perfect racing silks design. He concludes: ‘I’ve devoted myself to horse racing as other sorts of persons devote themselves to religious or political or cultural enterprises …’

Gerald Murnane (photograph by Shannon Burns)

Gerald Murnane (photograph by Shannon Burns)

‘He connects this sensitivity to colour combinations with synaesthesia, then talks about his quest for the perfect racing silks design’

The intensity of Murnane’s passion for racing is a source of humour at times. The two-page diatribe against the once-popular race caller Bert Bryant is one example. (Murnane calls Bryant the worst caller he ever heard, ‘a self-opinionated loudmouth’ and ‘an incompetent buffoon’.) In ‘Gerald and Geraldo’, Murnane makes frustrated but well-reasoned suggestions for regulatory improvements to racing, before declaring: ‘I can’t put it more simply than that, and yet the so-called experts have been getting it wrong during my seventy years as a follower of racing and probably for much longer.’ But he does go on, pleading with all ‘fair-minded readers’ to join him in his quest for justice. It is clear, during these sections of the book, that Murnane is addressing racing enthusiasts more than any other readership.

With Something for the Pain, Murnane abandons his ideal aesthetic model in favour of more accessible forms. Instead of a ‘notable and closely contested horse race’, the memoir reads as a convincing victory over a moderate distance. The sentences are expertly chiselled and each anecdote is well shaped, but deeper complexity is largely avoided. Murnane characterises the memoir as ‘a batch of recollected impressions and daydreams’, and those daydreams are always interesting, but only occasionally wondrous.

‘We Backed Money Moon’ is typical of the whole: what begins as a fairly mundane recollection from childhood is briefly transformed into a sublime experience when the young Murnane encounters a ‘dream-world brought into being by the sight of richly tinted drinks and the sound of mellifluous horse names.’ The title story, ‘Reward for Effort’, and ‘Lord Pilate and Bill Coffey’ maintain this balance between the everyday and the sublime, but Murnane is less ambitious elsewhere.

‘Form-Plan and Otto Fenichel’ is a dry and witty anecdote, but little more than that; ‘Summer Fair and Mrs Smith’ is an enjoyable yarn; and ‘Basil Burgess at Moonee Valley’ is almost purely descriptive. The value of these recollections and musings, like most of the book, is in the glimpses they offer of Murnane’s life, refracted through the prism of an arcane obsession. Among other things, we learn about his relationship with his father and unease around women, his drinking habits and solitariness, and his mystical sensibility.

Something for the Pain bears testament to a lifelong obsession and further illustrates the breadth and depth of meaningfulness that Murnane can draw from a seemingly straightforward spectacle. Those who are totally unfamiliar with racing will learn much – both historical and technical – about the subject, and readers who have never encountered Murnane’s fiction will discover an approachable, if faintly eccentric, storyteller.

Comments powered by CComment