- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

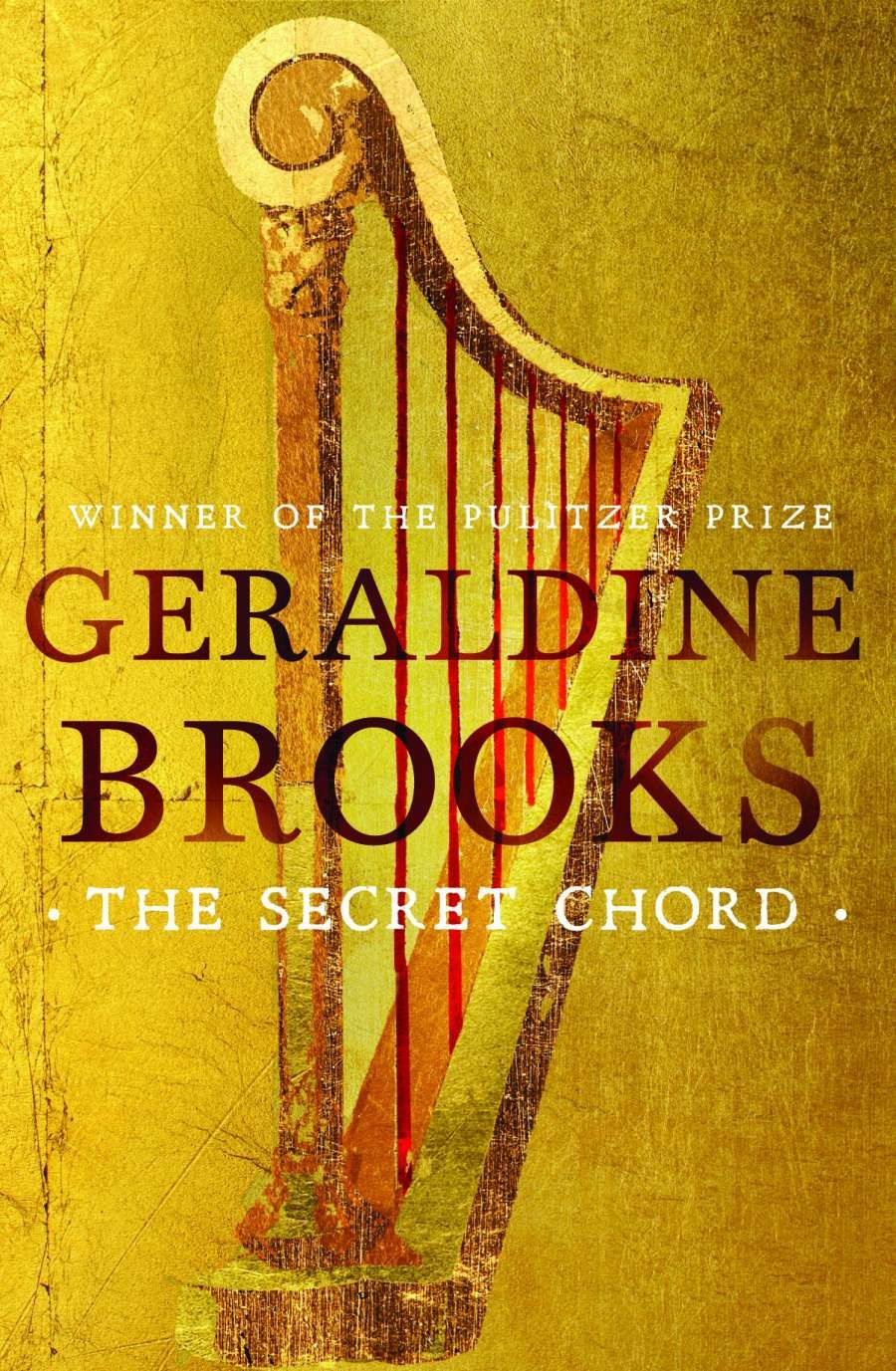

- Custom Article Title: Morag Fraser reviews 'The Secret Chord' by Geraldine Brooks

- Book 1 Title: The Secret Chord

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $39.99 hb, 400 pp, 9780733632174

Nathaniel also provided Brooks with a name and narrative device that enabled her to embody the metaphysical reaches of David’s story. While trawling through sources, she found ‘tantalising’ references to a ‘missing book of Natan’. So Natan, David’s seer and scribe, became her voice, the teller of her tale. It is Natan, the truth teller, the reluctant prophet burdened by his gift, ‘the blast from heaven, issuing from my mouth’, who inscribes on scraped calfskin the life of the man he follows, loves, and castigates. It is Natan who writes a history ‘forged from human voices, imperfect memories, self-interested accounts’, a history that becomes the world’s oldest recorded ‘biography’. (Brooks uses transliterations from the Hebrew of the Tanakh for personal and place-names throughout The Secret Chord: hence, for example, Natan, Yishai, Shaul, Yonatan, Batsheva, Shmuel, Shlomo, and Plishtim for Nathan, Jesse, Saul, Jonathan, Bathsheba, Samuel, Solomon, and Philistine. You might pencil a translated genealogy inside the extra cover pages of your book – an old tradition, and it helps.)

Scholars dispute David’s story; some question whether he actually existed. But Brooks is not writing biblical history or cultural anthropology: she is an assured novelist who has used her considerable skills (including as an investigative journalist) to tell a coherent, epic story that resonates, tragically, for our own strife-ridden century. She seems unhampered and convincing in staying close to the historical accounts – no small feat given their complexity. If you find the genealogies challenging, try mapping the battles and sexual politics of an era where tribal skirmish and warfare was a way of life for men and boys, and women were traded for strategic and dynastic advantage (plus ça change?).

‘Music is crucial to Brooks’s novel – the warp to its narrative weft’

Brooks’s investigative doggedness bears fruit in her novelist’s prose: you can tell from the authority of her phrasing that she has walked the land she writes about: ‘The road to Beit Lehem is through the hill country and soon enough, the land began to rise again.’ She has immersed herself in historical domestic detail and deploys it metaphorically: David’s rape of Batsheva, wife of Uriah, his loyal Hittite commander, is a matter that ‘would need to be covered up, and swiftly. It was the kind of thing that corrodes, like a drop of lye fallen upon linen.’ The textures and smells – of battle clothes, kine pens and dun cakes set downwind, of wood and gut used to fashion a harp, of the Philistine’s iron-forged armour, of garments, regal, stained or grief rent – are precise, recreating a whole world, without strain or scholarly pedantry.

Geraldine Brooks (photograph by Randi Baird)

Geraldine Brooks (photograph by Randi Baird)

It is challenging for a novelist in our time to write authentically about a world in which prophecy was potent. Brooks, like Hilary Mantel, is adept at projecting convincingly into other times, other world views. She uses her Natan with subtlety, making one want to know more, rather than less, about this strange man, about what he could do, and those he influenced, including his giant-killing David; more about what constitutes wisdom and forethought; more, perhaps, about the prophet Ezekiel’s supposed epilepsy and the implications of that latter-day diagnosis. She makes you want to search out the way history has seen these men and women, just as Mantel has sent crowds into London’s National Portrait Gallery to seek out the (unilluminating) portrait of Thomas Cromwell.

What Brooks does – and it is the novel’s strength – is set her reader on a great search by opening up a compelling vista of humanity and leaving you hankering after more. She will make you think further about the fate of women, then and now. This is, after all, the writer who gave us Nine Parts of Desire: The Hidden World of Islamic Women (1994). Her women in The Secret Chord are fully fleshed, as complex as David himself. Their lives may be constrained, but their minds cut like etching tools into our consciousness.

Brooks also lays before us the grand duty of thinking more about the power of music – to stir, incite, delight, and to anneal. Do we believe, with Shakespeare’s Caliban, whom she quotes in the book’s dedication (to her son Nathaniel), that:

The isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not?

Comments powered by CComment