- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

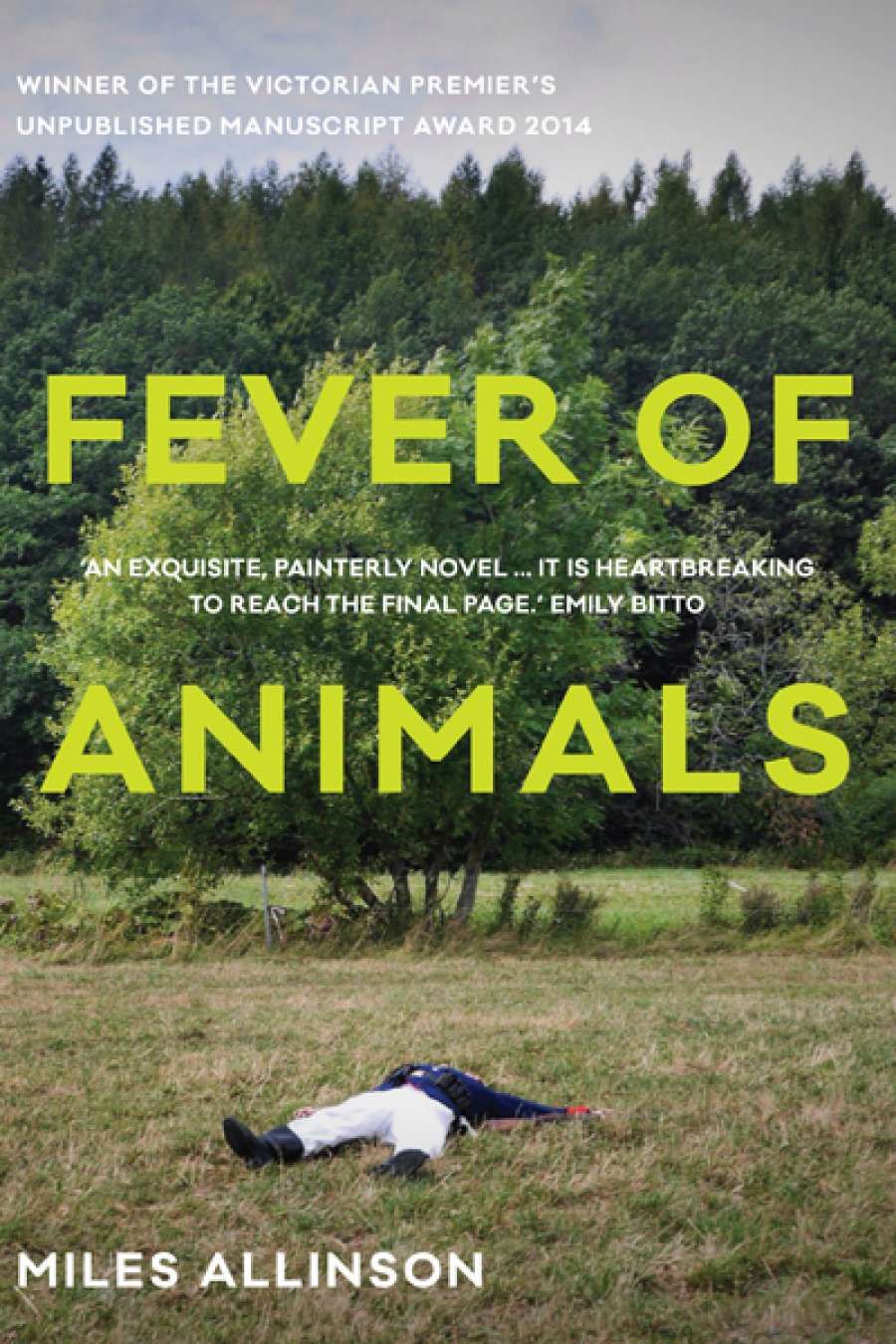

- Custom Article Title: Catriona Menzies-Pike reviews 'Fever of Animals' by Miles Allinson

- Book 1 Title: Fever of Animals

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $29.99 pb, 256 pp, 9781925106824

The echoes that Miles discovers between his life and Bafdescu’s entangle his narrative of self with the ostensible work-in-progress. His subject becomes a kind of alter ego. Does Fever of Animals begin with Miles Allinson, who has bestowed his first name upon his narrator? I have no idea. Is it all make believe? That, certainly not. The play between truth and fiction, between the writing self and the self written, is one of the great pleasures of Fever of Animals. A Google search for Emil Bafdescu leads only to news about Miles Allinson: he won the 2014 Victorian Premier’s Unpublished Manuscript Award for Fever of Animals, and the novel has been picked up by international publishers.

The narrator, whatever his relationship to Miles Allinson, is hardly a reliable arbiter of the lines separating the real from the imaginary. Miles is prone to failures of memory and recognition. ‘Remember this, I told myself. Remember everything! Of course I didn’t.’ He often gets drunk. We cannot rely on him to get the details right; indeed, Miles explicitly disavows this responsibility, letting the deeper currents of desire and grief dislodge stable narrative elements. He confesses that he has lied to the reader; he writes an emphatic account of an event and later sheepishly revises it. The effect may be disorienting, but the result is an engrossing account of the writer at work: the vacillations, doubts, crises, and self-indulgence of his character are acutely captured.

Emil Bafdescu exists only within the pages of this book, but the circle of surrealists who surround him in Fever of Animals are carefully sketched from the annals of art history. Miles undertakes a research process that reflects Allinson’s own inventive literary detective work. Miles attends a conference in Bucharest devoted to the work of Ghérasim Luca (an actual Romanian surrealist, who is here cast as one of Bafdescu’s friends). He tries to look inconspicuous as he sits through hours of academic presentations delivered in Romanian, hoping for a breakthrough about his subject. This is a brilliant scene, full of sharp details about the surrealists and their amanuenses, and it is very funny.

Miles Allinson

Miles Allinson

‘The play between truth and fiction, between the writing self and the self written, is one of the great pleasures of Fever of Animals’

Fever of Animals is also a book about love. Allinson is less imaginative when it comes to Alice, the woman whom Miles cannot forget and does not understand. She functions as a muse of sorts, and Miles gazes into the broken mirror of their relationship to make sense of his own ego. I was troubled by the uses to which the quiet Alice is put in this narrative. The early stages of their attraction leave Miles submissive with desire, but as the relationship progresses Alice loses personality and agency. Bedridden after a traumatic incident, she is literally left immobile. Empathy eludes Miles; he pursues the mystery of Bafdescu instead. Is Miles’s inability to conceive of Alice except in relation to himself a tactic in Allinson’s characterisation of a self-absorbed young artist? If so, it’s very convincing.

Alice is less obscure than she is obscured in Fever of Animals. As an object of desire and frustration, she sits comfortably within a modernist tradition of representation that obviously preoccupies Miles. Capricious, crazy women such as Breton’s Nadja and Cortázar’s La Maga would be at home on his bookshelf. I wished Miles had happened upon a book like Kate Zambreno’s Heroines (2012), which takes up the fate of the mad women of modernism – the muses and lovers – and critiques the uses to which they are put by male artists.

Allinson has thought deeply about the traditions in which he is writing and is willing to meddle with their trajectories. He has created an artist with whom his own intense protagonist can be obsessed. Fever of Animals is audacious, clever, and original. Why, then, must his muse, the only significant female character in this fever dream, be so damaged and so silent?

Comments powered by CComment