- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

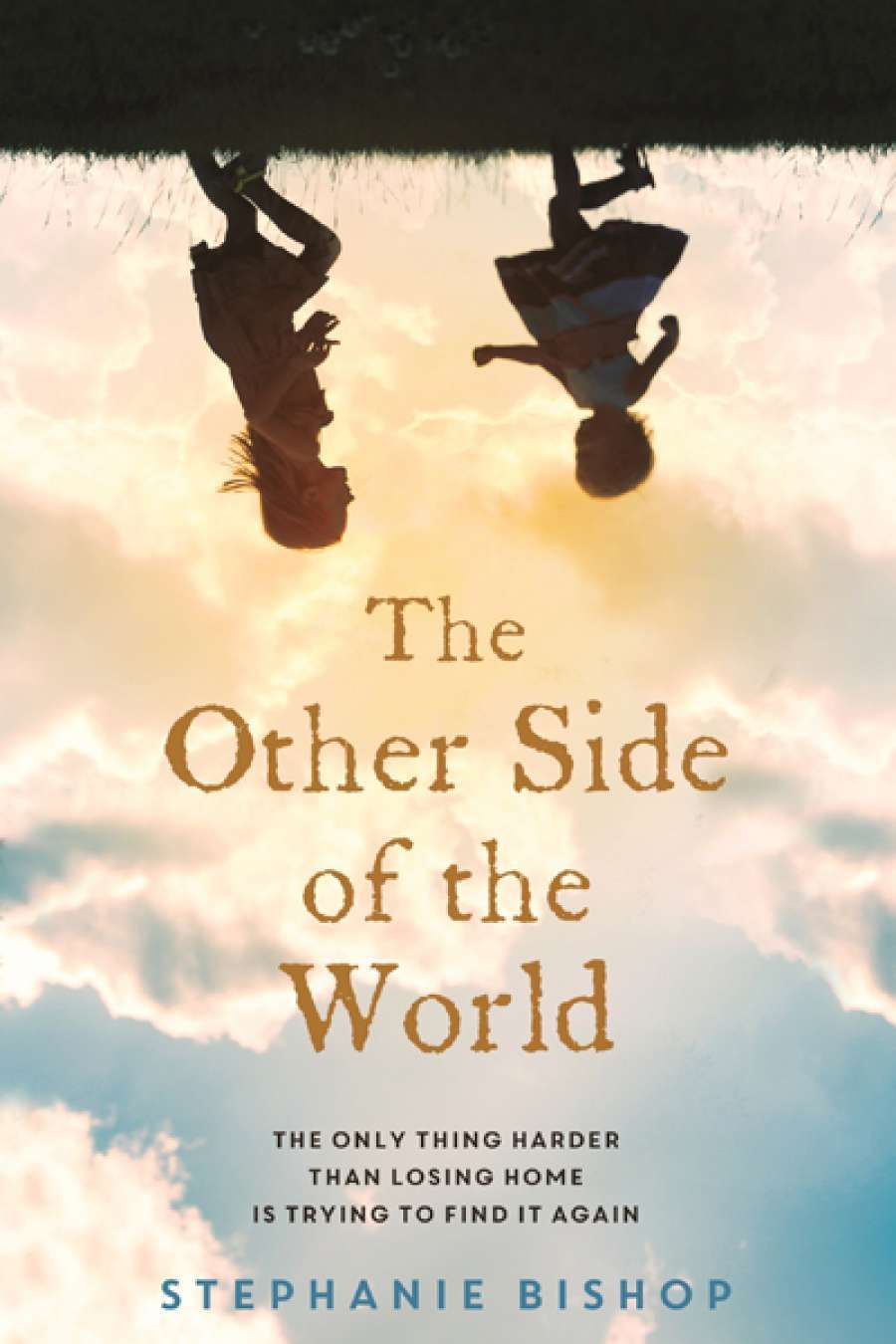

- Custom Article Title: Jane Sullivan reviews 'The Other Side of the World' by Stephanie Bishop

- Book 1 Title: The Other Side of the World

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $29.99 pb, 352 pp, 9780733633782

The problem in The Other Side of the World is that the husband wants to go to Australia and the wife wants to stay put. As Bishop develops the tensions in her beautifully observed and deeply poignant second novel, it is not just a question of sorting out where these people should live. The whole delicate fabric of marriage and parenthood, of identity and duty, even love itself, is at risk.

We see events mainly from Charlotte’s viewpoint. She is married to Henry, an Anglo-Indian academic. They live in a cottage in Cambridge with a small daughter, Lucie; then a second daughter, May, is born. Charlotte is an artist who fits her painting around her wifely and motherly duties. The house is too small, the children are sickly and fractious, everything is cold and damp. Henry gets it into his head that their problems will be solved if they emigrate to sunny Perth. He shows Charlotte a brochure with a picture of two women waterskiing.

Charlotte won’t read the brochure. She is happy where she is, in a way she can’t explain to Henry or even to herself. Despite the winters and the horrible weather, she loves to walk in the flat empty fields: ‘It is as if the place has chosen her.’ She never exactly agrees to go to Australia, but she says yes – because he is her husband, because it would be better for the children, because she doesn’t know what else to do.

And so Henry finds a new job, and they find themselves in a bigger house in a Perth suburb, close to the river and the sea. It is unbearably hot. There are mysterious changes in light, wind, and time. Charlotte, waking to a long day alone with the children, feels exhausted. She can’t paint. Months pass; everything inexorably goes downhill.

This sounds like dark, dreary reading, but it is luminous. The light breaks through in the precision of Bishop’s observation of small things: the way Charlotte struggles to keep her petunias alive; the way Henry soaps her back in the bath; the way a eucalyptus tree can appear dull one day and extraordinary the next; and above all, the way the two lively and demanding little girls dominate Charlotte’s life.

Stephanie Bishop

Stephanie Bishop

Bishop has a sharp eye for the paradox of children: how you can love them to distraction and at the same time feel they are suffocating your essential self. She describes Charlotte’s distorted vision after she spends the day with the baby and then sees Henry come home: ‘How foolishly large adults seemed then, how odd-looking they became – almost monstrous – with their sprouting tufts of hair and yellowed eyes and slabs of flesh and creases.’

But Henry as depicted by Bishop is far from monstrous. She gives a deeply sympathetic portrayal of a man in pursuit of an impossible nostalgia for his childhood in India, a man who does not belong to any particular place but pretends he can belong anywhere. His insecurity and his sensitivity to casual, unconscious racism are painful to read. He and Charlotte still love each other, but the change of place has created a rift – or perhaps the rift was always there, and Australia is a metaphor for the yearning that cannot be fulfilled.

‘The light breaks through in the precision of Bishop’s observation of small things’

As the story goes on, I worry more and more about Charlotte and those children. The harried, exhausted mother has a fierce desire for freedom that slips into savagery – not abuse, but something close to snapping point, as in a superbly tense scene where the children cry out for her attention and she keeps beating a carpet. Today we read many Australian stories of cruel, blatantly dysfunctional families: this is a story of quiet, decent folk who would never go there, but there is a journey nonetheless to places where a decent person should never go.

Bishop’s focus on mother, father, and children is so all-consuming that the other characters are only lightly drawn, and this is sometimes inimical to her purpose. The resolution of the story also depends on an unlikely coincidence. Not a perfect novel, then, but a disturbingly fine one, where the gentle, meditative prose belies the fractures running along the seams of identity, partnership, and parenthood. Only love can save this family: but is love enough?

Comments powered by CComment