- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Kevin Rabalais reviews 'Every Time a Friend Succeeds Something Inside Me Dies' by Jay Parini

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

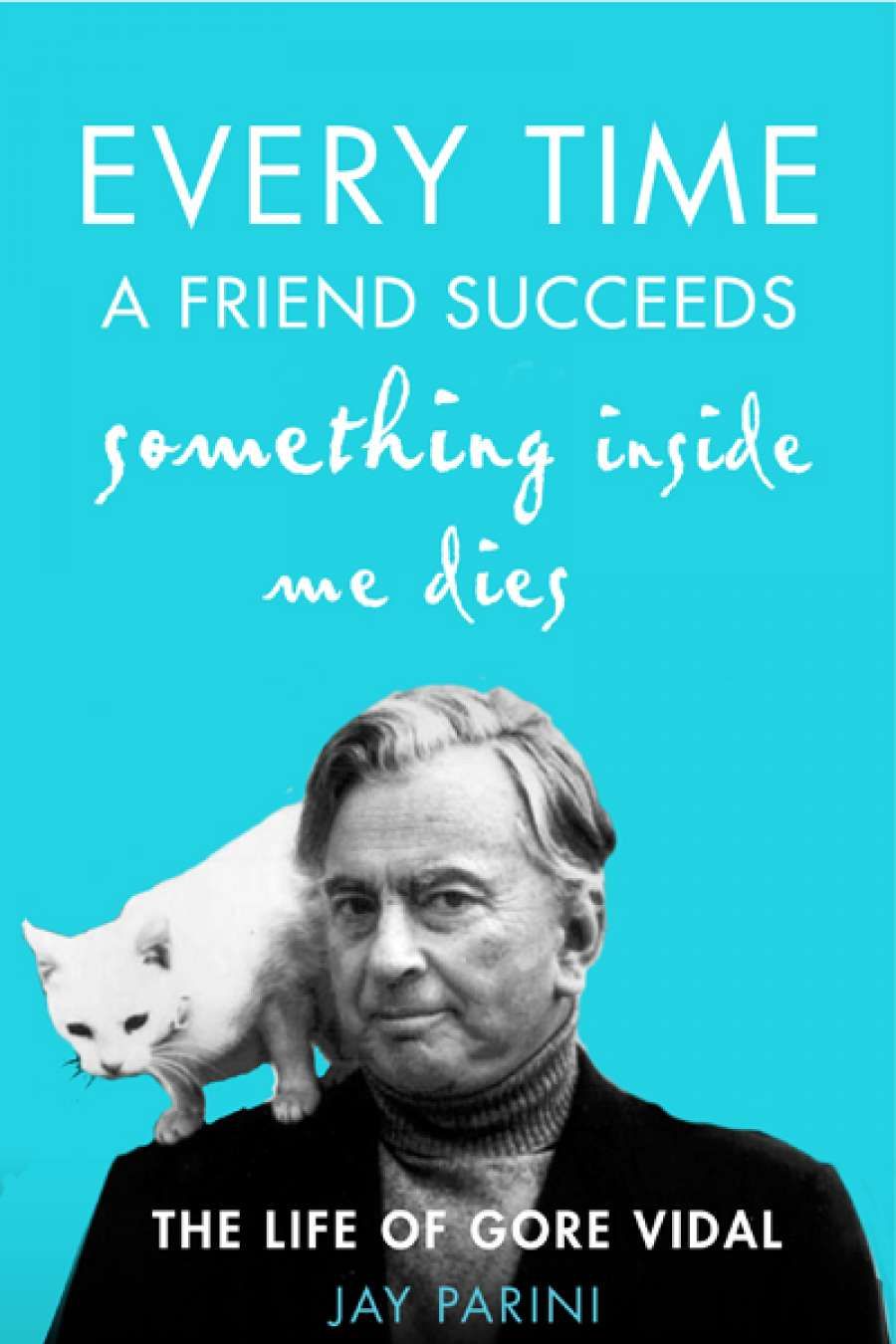

- Book 1 Title: Every Time a Friend Succeeds Something Inside Me Dies

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life of Gore Vidal

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $55 hb, 412 pp, 9781408704639

With the mere mention of his name, even those who have never read Vidal’s essays – the highlight of his output – often sense a heavyweight looming in the literary consciousness. For half a century, he remained a predominant cultural force. Readers expected him to weigh in on any important political or literary topic. In doing so, he always played his favourite role, that of Gore Vidal, the writer as famous public figure. Here he is, expressing his views in The Nation, the New York Review of Books, and Da Ali G Show; there, acting in the cult classic Gattaca or Tim Robbins’s satirical mockumentary, Bob Roberts.

Vidal’s presence, or what Parini labels his ‘empire of self’ – at times snarky, always urbane – infiltrates all of the above. We find it, notably, in the twenty-six volumes of non-fiction that made him one of the most confronting and divisive figures in twentieth-century letters, a heroically prolific writer who welcomed all the attention and controversy that came with cultivating a literary presence we will probably not see the likes of again. Parini and admirers such as Christopher Hitchens, an early acolyte and late rival, believe Vidal created his best and most enduring work in his essays. Vidal redefined the genre. He melded the personal and the philosophical and forged an inimitable voice both eloquent and barbed. Little escaped his notice. He proved equally nimble when writing about John F. Kennedy or John Updike, Sinatra or 9/11. The same, too, when he dropped the names of famous friends on The Tonight Show or verbally fenced on television with his nemesis William F. Buckley Jr in a series of debates broadcast to millions of viewers during the 1968 US presidential nomination conventions. (The latter is the subject of a documentary, Best of Enemies, out this year.) Late in his life, the same man who shared stages with Noam Chomsky played himself on The Simpsons and Family Guy.

In 1960 John Kennedy arrives at The Best Man to meet the cast and screenwriter Gore Vidal.

In 1960 John Kennedy arrives at The Best Man to meet the cast and screenwriter Gore Vidal.

Parini’s title is a variation of a typically Vidalian quote, the kind that allowed the author to flaunt his ego through a parade of acerbic yet erudite wit. Empire of Self, the biography’s American title, more closely reflects the persona that Vidal carefully constructed. His career commenced at a rapid pace. Beginning with Williwaw, Vidal wrote six novels in less than five years. ‘[N]one,’ Parini writes, ‘ ... was more than the work of a brilliant apprentice.’

Vidal’s famed verbosity sent him down many dead-end corridors. In various forms, he failed and tried again, always stalking fame and the money he believed it guaranteed. There were forays into writing for television and film. Less well known are his pseudonymous mystery novels, written, and sometimes dictated, in a week or two. One of these, Thieves Fall Out – lost for more than half a century and reissued this year – reveals one more side of Vidal, that of pulp writer. It adds another layer of complexity to the man who, following 9/11, became more relevant than ever, providing a rare liberal voice in the mainstream media.

Parini, a novelist who has written biographies of Robert Frost (1993) and William Faulkner (2004), shared a decades-long friendship with Vidal. In the early 1990s, after Vidal solicited him to become his biographer, Parini realised that he would have to choose between friendship and the book: ‘ ... I decided then to write a book that could only be published after [Vidal’s] death, a frank yet fond look at a man I admired, even loved, and who had preoccupied me for such a long time.’ The result is, in parts, an unbiased biography that exposes Vidal’s flaws and critically examines the achievements and fiascos of an indispensable voice whose favourite topics to attack, among them America’s military budget and state efforts to regulate sexuality, remain headline news. Parini also includes brief first-person vignettes, published between each chapter. These scenes contrast a public figure whose ‘narcissism was, at times, an exhausting and debilitating thing’ with the man who lived his private life as a homosexual but who never allowed himself to be defined by his sexuality.

‘When he died, aged eighty-six in 2012, he left behind more than fifty books’

Born Eugene Louis Vidal, he changed his name at age fourteen. His maternal grandfather, Thomas Pryor Gore, served several terms as a US senator from Oklahoma. The family, however, was self-made, and Vidal received his education from the blind senator, sitting beside him in the Senate and listening to speeches that would influence his own later style as an essayist and politician. (Vidal ran, unsuccessfully, for the House of Representatives in 1960 and for the Senate in 1982.) The young Vidal gleaned something else from this experience: ‘They were distinguished and gifted actors,’ he said of the politicians he observed in his childhood. ‘If you studied them, it was like studying at the Old Vic.’

Thus, there were always at least two sides at work in Vidal’s performances. Both competed for adoration. This helps to explain the persona – egoist – that many summon when they hear his name. ‘The mask of Gore Vidal, the one he wore in public, did him a disservice in many ways, as it occluded the shy man hidden beneath its rubbery texture,’ Parini writes. Vidal’s ability to wear that mask provided entrée to the numerous stages over which he traversed and brandished his ideas, always fixated on what the writers of his generation considered the biggest of literary game: the novel.

Though his fiction struggled to find its place among critics and the academy, Vidal found a broad readership late in his life with his bestselling post-9/11 political pamphlets such as Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace and Dreaming War. Until his death, he continued to move between homes in Italy and the United States. ‘He made himself a citizen of the world,’ writes Parini, ‘not unlike Mark Twain or Henry James before him.’ In an essay on Dawn Powell that sparked a renaissance for a novelist who deserves another, Vidal writes of a golden age of fiction, now replaced by the television miniseries, when ‘there was still this romantic notion of the Great American Novel ... You were, if serious, a writer for life, with an ever-growing public if you were any good.’ It would be easy to dismiss Vidal as a man of his time, a literary curiosity that mass culture has exterminated. We would do better to become members of Vidal’s public. Parini’s biography provides the perfect primer.

Comments powered by CComment