- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

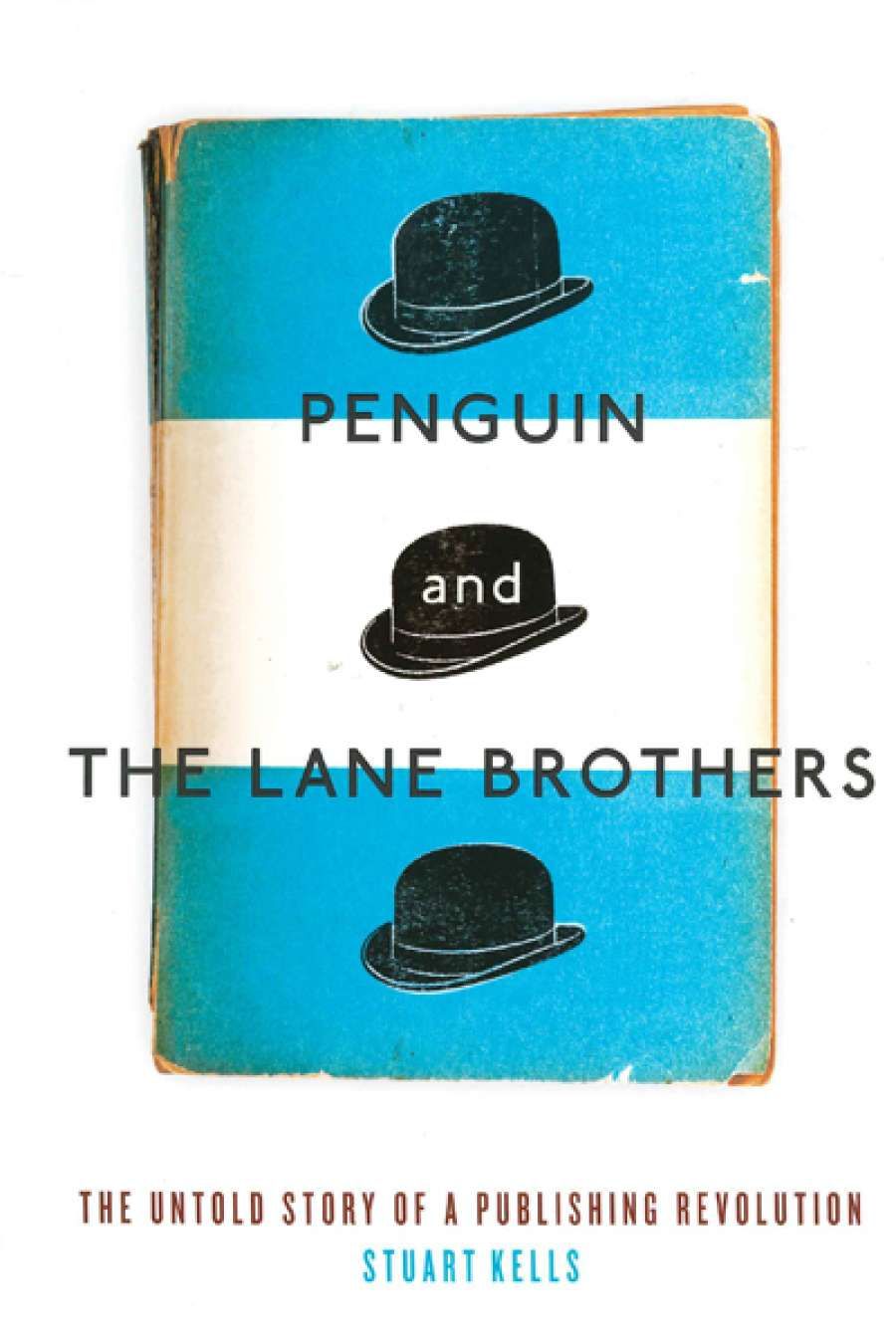

- Custom Article Title: James McNamara reviews 'Penguin and the Lane Brothers'

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Penguin and the Lane Brothers

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Untold Story of a Publishing Revolution

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $39.95 hb, 320 pp, 9781863957571

In London, the brothers came together to work in senior roles at Bodley Head. After Uncle John and his wife died, an inheritance made the brothers wealthy, with Allen taking a majority shareholding in the company. But Bodley Head was on a ‘slide into chaos and enfeeblement. The imprint that once yeasted London’s literary ferment was now crusty and inert’, close to liquidation. This turmoil gave the brothers ‘a platform from which to launch a laboratory of publishing experiments’. Core to these was publishing James Joyce’s Ulysses, which ‘had endured a bruising history in and out of print’. Important literary publishers (the Woolfs’ Hogarth Press and T.S. Eliot’s Faber) had declined to print it in England, fearing prosecution for indecency. The Lane brothers took up the challenge and, avoiding legal action, ‘Ulysses became a cash cow’. On the back of Ulysses’ success and Bodley Head’s demise, Penguin was born.

Penguin’s railway origin story is rebutted by Kells: Allen, unsophisticated in his reading, was hardly the progenitor. Rather, the Lane brothers picked up on a need, articulated by George Bernard Shaw amongst others, for quality books in affordable form. This need was already being serviced by overseas firms, Albatross and Tauchnitz (who, as Penguin would, printed paperbacks with distinctive, coloured covers). And the idea of sixpenny books had also been presented to Allen by two junior employees. ‘Small legible typefaces, paper covers, the “ideal” rectangular format, low prices, good design, ornithological branding, colour coding, mass printing, mass distribution – the Lanes did not invent any of the elements that came together in the making of Penguin.’ But the brothers were uniquely successful in amalgamating these trends and bringing the product to the British and international markets.

The Williams-Lane family. Left to right: Richard, John, Camilla (seated), Samuel, Allen, Nora (seated)

The Williams-Lane family. Left to right: Richard, John, Camilla (seated), Samuel, Allen, Nora (seated)

‘‘‘Uncle John’’ Lane, Oscar Wilde’s publisher and owner of The Bodley Head, needed an heir’

Kells compares Penguin’s start-up days with Facebook’s – although Penguin’s were rather more gothic. With roaring demand for paperbacks, Richard and John worked vicious hours with a small staff in their new premises, the ‘crypt at Holy Trinity’ (Allen was often absent). This dank warehouse of books and the dead was accessed by ‘an unsafe electric hoist … that had previously lowered coffins … A curtain could be dropped to cover the glamour-girl pictures should Holy Trinity’s vicar ride the creaking hoist down.’ A worker stacking books ‘fell right on top of a coffin with sufficient force to smash it open’ into ‘a cloud of dust and the bones of a West Indian official’. ‘Books stored among the coffins for any appreciable time got a crypt smell that lasted for years.’

When World War II broke out, the firm prospered. Richard and John served as naval officers, but continued to review manuscripts, some of which were destroyed when the ship they both served on was sunk (as good an excuse as any for lost pages). In fact, the war was good for Penguin: ‘the demand among soldiers, sailors and airmen for pocket-sized paperbacks was very high.’ Cooperation with the government to form the Forces Book Club led to ‘their firm [becoming] an integral part of the war economy’ and ‘a national institution’.

Early Penguin delivery van

Early Penguin delivery van

‘Kells compares Penguin’s start-up days with Facebook’s – although Penguin’s were rather more gothic’

Penguin’s continued story is one of growing power, as the firm expanded into overseas territories and survived (profiting immensely from) the obscenity trial that followed its uncensored publication of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. For the brothers, the story was bleaker. John was killed in action and the golden bond between Allen and Richard broken. According to Kells, Allen engaged in a long-standing and nasty campaign to tarnish Richard’s reputation. It got worse: Allen abused Richard’s trust to take control of the company and, ultimately, misled Richard into selling his remaining shares to Allen at a vast undervalue. Kells is clearly on Richard’s side: lionising him as an affable, competent, literary businessman – the ‘master builder’ of the firm – and painting Allen as a man of contradictions, but ultimately a fickle and incompetent tyrant, who succeeded only on the back of his brothers’ work, and then took ruthless advantage of Richard’s blinkered love. Marshalling previously unseen primary source material, Kells celebrates Richard Lane’s enormous, unsung influence on Penguin.

At times, Kells’s access to Richard’s papers leads to a surfeit of detail (do we need a quantification of Richard’s cuff-links?). A tighter selection might have allowed more of John’s story, which, notwithstanding his early death, feels underdone. The lean notes – linked, confusingly, to fragmented quotations – undermine the usefulness of Kells’s laudable work on the primary sources. And there are far too many bird metaphors. But these are, ultimately, minor critiques of an otherwise engaging, sharply written, and important revisionist history of a great literary institution.

Comments powered by CComment