- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Some stories deserve to be told more than once. Retold, they cannot be the same. Even when the teller is the same person, the shift in time and experience will make the story new. In The Ghost at the Wedding, Shirley Walker returns to the material of her autobiography, Roundabout at Bangalow (2001), in order to focus more closely on the saddest and most powerful memories therein: those of the young men of her family who served in two world wars.

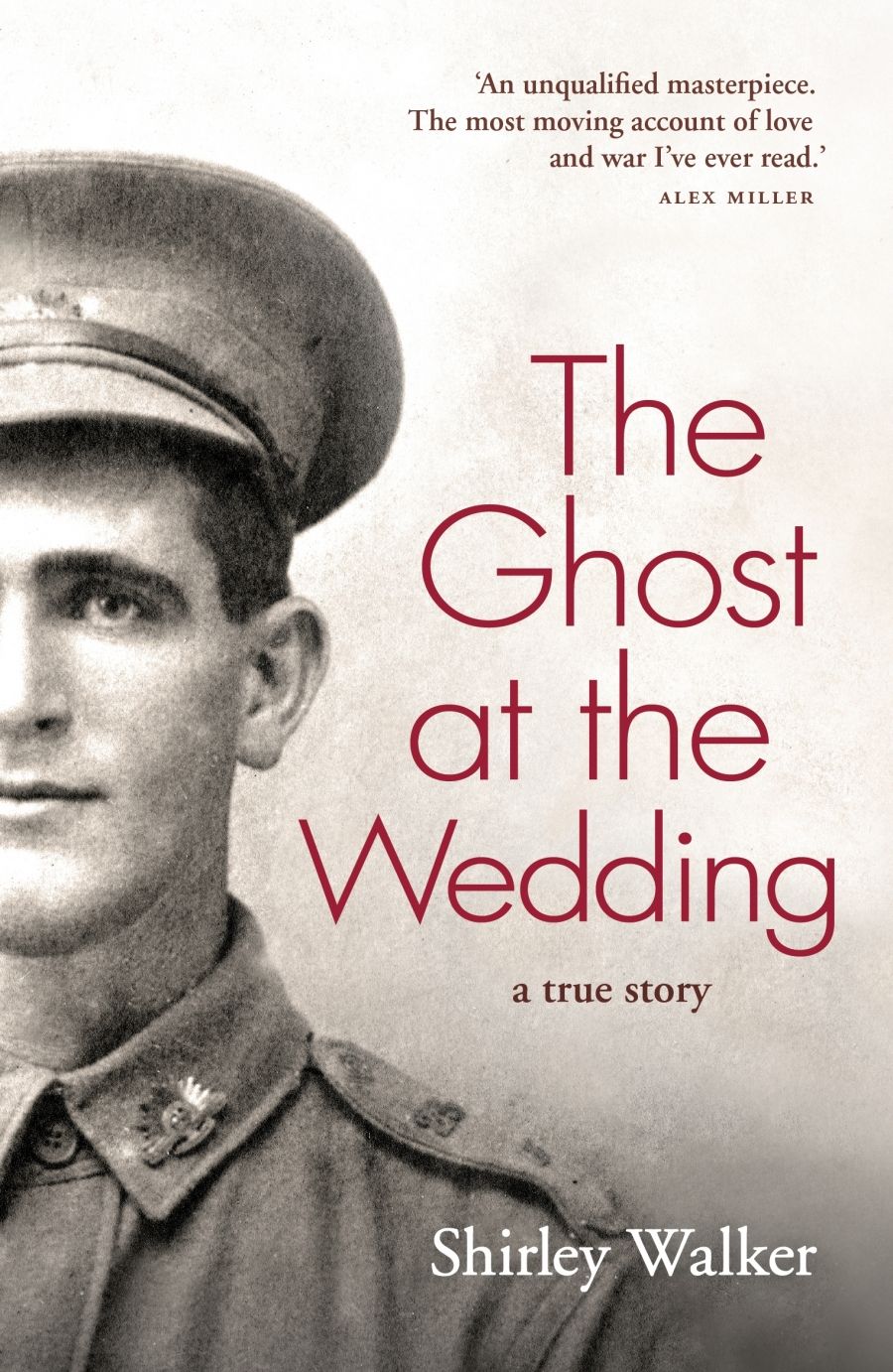

- Book 1 Title: The Ghost at the Wedding

- Book 1 Subtitle: A true story

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking $32.95 pb, 247 pp

As the story of a talented young woman from rural Australia growing up in the early 1940s, Roundabout at Bangalow invites comparison with Jill Ker Conway’s much-praised The Road from Coorain (1993), which in some ways it surpasses. The sense of place, in rural Australia, is strong in both, as is the narrative drive. Both stories are shadowed by family tragedies. Walker’s story is richer than Conway’s, more observant over a wider social range. Written when the author was in her seventies, it illuminates period and place from the Depression years to the present day.

Unlike many of her brilliant contemporaries, Walker did not leave Australia in order to fulfil her talents. Most of the significant events in her life took place in the northern rivers region of New South Wales, near Lismore, where she was born, or on a soldier settler’s block in northern Queensland, where she lived as a young wife and mother. Her education, which brought her an outstanding academic career in middle life, was hard won, but she sums it up buoyantly: ‘I was always lucky.’

Walker extends the family story in The Ghost at the Wedding with a sharper and more detailed narrative of the experience of the two war generations. She places herself at the edge, an unobtrusive presence who seldom intrudes in the first-person voice. As storyteller she shapes the inherited memories, draws out their meanings and meditates on uncertainties. At the centre are four young men from two families, linked by friendship and later by marriage, who volunteered for World War I. Three were killed. The one who came home was irreparably damaged, physically and psychologically.

When Eddie Walker married Jessie Linton, sister of his dead comrade, he was carrying an almost intolerable burden of rage. The family he and Jessie founded was held together precariously, often fearfully, but with love and hope. World War II intervened to claim the next generation. Leslie Walker, son of Eddie and Jessie, survived the war against Japan. He and the author were married in 1947. Jessie’s memories, passed on to Shirley, form the central part of this book. Although we follow the young men to the trenches in France and the jungles of New Guinea, this is Jessie’s book.

The first ghosts at Jessie’s wedding came from an earlier time than the 1914–18 war. Her forebears were dispossessed rural labourers from Scotland. Choosing exile rather than starvation, they brought bitter memories of greedy landlords, as well as longings for their lost familiar places. One story of the voyage to New South Wales, as horrifying as the grimmest ballad, was passed down in the family. A mother, worn out by her baby’s persistent crying, said, ‘if he didn’t be quiet she would throw him out the porthole’. She stepped outside the crowded cabin to calm herself. Returning, she found an unnatural silence. Her three older children were ‘smug, self-satisfied’. The baby had kept on crying, so they shoved his little wriggling body though the porthole, into the tumultuous sea. Truth or myth? This haunting lost child story is more like folklore than documentary. Walker offers it as a symbol of nineteenth-century immigrants, destitute and illiterate, lost between hemispheres.

Many of these immigrants prosper and learn to love the land they cultivate in New South Wales. Others are not so lucky. Eddie Walker, who is befriended by Jessie Linton’s family, has a story of poverty and abandonment in Sydney: an Irish mother who died young, and an ineffectual Swedish father who gives up his three sons to an appalling childhood in a Catholic orphanage. Somehow they survive a cruel system, only to reach manhood in 1914. In love with Jessie, Eddie goes to war and serves in France, where his brothers, Leslie and Oscar, and his best friend, Joe Linton, are killed. Maimed and disfigured, Eddie comes home and marries Jessie.

World War II claims the next generation. The ‘replacement children’ who carry the names of the dead men (another Joe, another Oscar, another Leslie) fight in the Middle East and in New Guinea. Leslie survives to carry on the family line, and to bring up his and Shirley’s children without the bitterness and anger which was his father’s legacy from World War I. The farmhouse on stilts that Eddie built on a riverbank, surrounded by macadamia and pecan trees, becomes a symbol of stability and renewal for the next generation. The ghosts recede.

Brenda Walker, daughter of Leslie and Shirley, has written a fine novel about the Gallipoli generation, The Wing of Night (2005), which is told mainly from the viewpoint of the women left behind. Though it has a West Australian setting, it draws on the family stories. Shirley Walker’s moving and eloquently written new book stands somewhere between fiction and memoir. She has felt free to imagine the thoughts of Jessie and Eddie, but she has also used family letters and other documentary sources. Best of all, she has used paintings as a way into Jessie’s emotional life.

Jessie, who always wanted to learn how to paint, was in her sixties when she took a few lessons and astonished her teacher at the Grafton Technical College with works he could not classify. With their rich, bold colour, their disregard for proportion and the strangeness of their vision, they were nothing like the works of the other elderly women in the class. Instead of painting gumtrees or vases of flowers Jessie painted ‘the passion for home and shelter that she had never been able to put into words’. Later, she painted her rage against the war, with grotesque versions of bemedalled generals in an upper panel and below them drowned figures, some limbless or headless, to represent the dead young men. Lessons in perspective were no use to her; that was not the way she saw life.

The Ghost at the Wedding, like Jessie’s paintings, gives imagination its place. It reminded me of Alice Munro’s quasi-fictional work The View from Castle Rock (2006). Like Walker’s, Munro’s story is part documentary, part imagined, and it begins with a voyage from Scotland: ‘Their words and my words, a curious recreation of lives, in a given setting that is as truthful as our notion of the past can ever be.’

Comments powered by CComment