- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Emily Ballou’s first book of poems opens with a quotation from Coleridge’s Definitions of Poetry: ‘Poetry is not the proper antithesis to prose but to science. Poetry is opposed to science.’ A book of poems on the life of Charles Darwin must be a refutation of this idea, though I had expected a more direct return to the comment which, two hundred years after Coleridge wrote it, has accrued greater meaning. In Coleridge’s time, the dazzling and potentially alienating specialisation of the sciences had not occurred, and C.P. Snow had never hailed the ‘two cultures’. Anti-intellectualism had not yet colluded with postmodern suspicion of reason to decry the malign, hegemonic nature of Western science. Coleridge, like many educated men of his time, was conversant with the latest advances in most branches of the sciences. He enjoyed a close friendship with Humphry Davy, the foremost scientist of the day, who also wrote poetry.

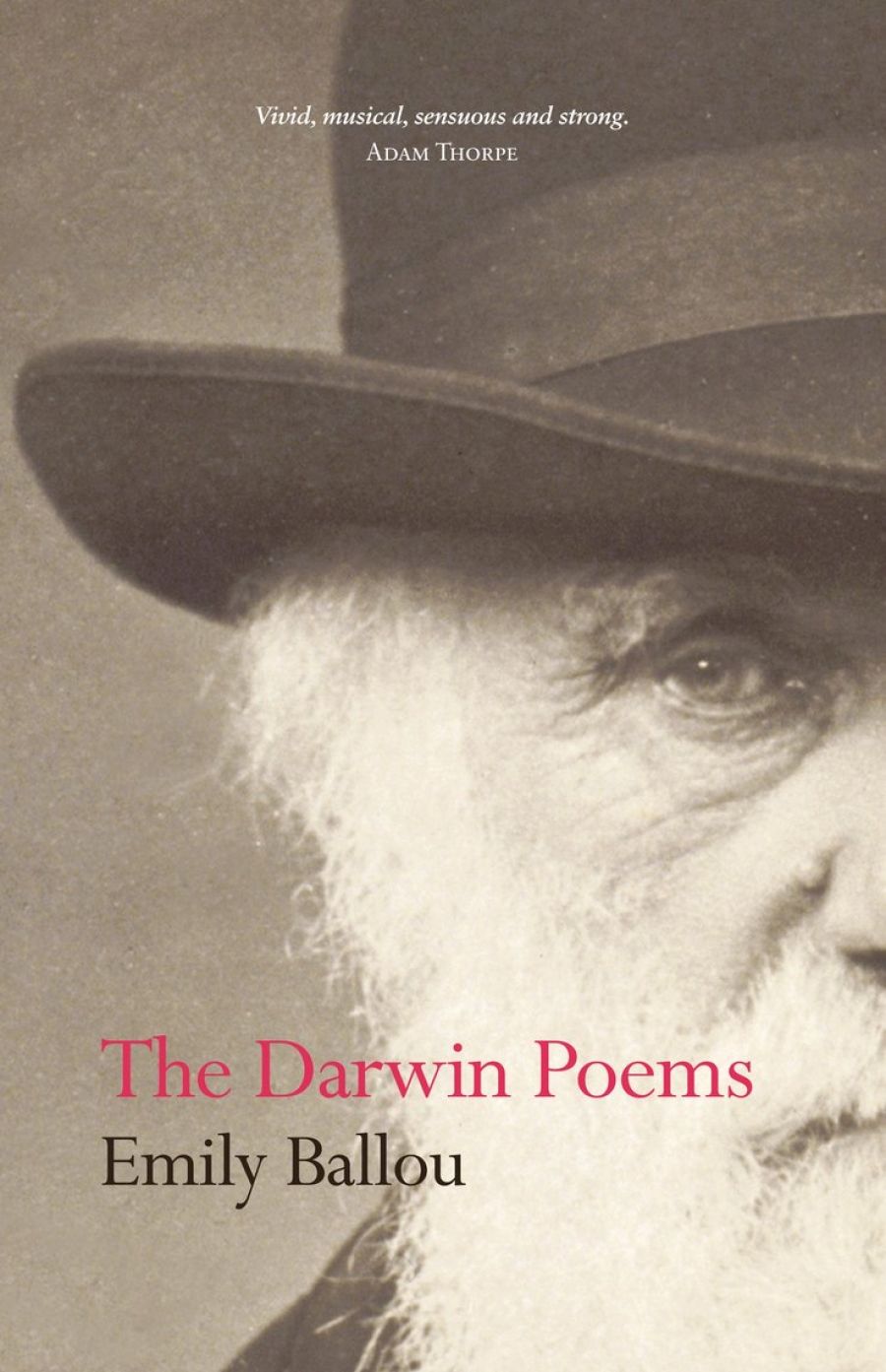

- Book 1 Title: The Darwin Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Western Australia Press $24.95 pb, 220 pp

Which is not to say that Coleridge was not on to something. Metaphor, the main tool of poetry, can usually be defined as scientifically untrue. My eyes are, objectively, not lodestars, and it is science’s mission to discover what they are, and how they came to be that way. Coleridge was disturbed by the way the scientific explanation might seem to strip away his power and freedom to identify my eyes as lodestars, or anything he pleased.

In her notes, Ballou says of her epigraph, ‘I haven’t taken it too seriously’. This is a pity; today, the opposition carries a multitude of assumptions it is too easy, too obvious. The Darwin Poems critiques it, never directly, but quietly and partially, using extensive quotations from Darwin’s letters and writings, including comments about science and the ‘poetical’.

One of the things the book does well is to use metaphors taken from science plausibly, without debasing their actual scientific content. The poems insist on the imaginative nature of science, the wonder and for Darwin, approaching his revolutionary conclusions, the terror. One of the best poems has Darwin walking in Argentina, with Wordsworth as his imaginary companion. The poet, loving nature, feeling that it can be greeted, incorporated into his imagination, as a benign source of wonder and enlargement, has no trouble with it. Darwin, seeing the indifference of natural forces, is less comfortable. The Romantic position is here the easier, Darwin’s dogged truth-seeking the more heroic, and even more imaginative path.

At one hundred and eighty-eight pages of poetry, the book is too long. Of course, Darwin’s own Victorian milieu could direct the length: the writer and reader of capacious books, Darwin lived in an age with a longer attention span and more free time. But in this case, and in view of Darwin’s own evocative prose, one might expect other Victorian stylistic inclusions: perhaps a denser poem, a longer line, or some use of traditional forms.

Instead, the verse is free, and the rhythms mostly those of twenty-first-century conversation. Some poems are superfluous, and tend to reportage, a hazard of poetry which tells narrative through loose forms. Poems often sound flat, with odd, twee moments of alliteration and internal rhyme. At other moments, line-breaks are used effectively to assert the strangeness of the subject-matter: ‘In the ringing forests of Brazil / even the frogs came out for evening song / matched the crickets in chant / & lit by the flashing green matter / of fireflies, recalled to him the bright / heartbreak of Malibran’ (‘Forms for Rapture’).

What the book does best is capture and insist upon the wonder of the natural world, and Darwin’s continual consciousness of this: ‘he who lived his days in two times: / one geological, philosophical, everlasting; / the other, fast, insignificant, human days, / tasks, clocks, life-time’ (‘The Time Traveller’). Just as the poet might see as a poet – Wordsworth continuously finding metaphor in clouds and country lanes – Darwin views all as a scientist, ‘bending / and unbending / his mind’ (‘Afterwards’).

As the poet recognises potential for creation in his surrounds, the scientist senses a kind of unfolding of deep time, a view that might be seen as the more respectful. As Darwin himself wrote, ‘there is a grandeur to this view of life’ (The Origin of Species, quoted in ‘The Orchis Bank’).

The depth of Ballou’s research is impressive, and helpfully recorded in lengthy notes, though of course there are a few factual niggles. Whilst he did love music, it is unlikely that Darwin was ever ‘humming a Welsh tune’ (‘Definitions for Happiness’) as he was profoundly amusical (friends played a slowed version of ‘God Save the King’ and challenged him to pick the tune: he could not). Little things like this don’t matter much; Ballou’s Darwin is generally convincing, and it is easy to share her sympathy for her subject.

I hope that readers who had not already imagined a young, adventurous Darwin, a doubting, thought-wrestling writer, a loving father and, finally, a suffering, sorrowful elder, will find him here. Readers who want more Darwin poems might try the English poet Ruth Padel’s Darwin: A Life in Poems (2009).

Comments powered by CComment