- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Thirty-four years after the former colony of Portuguese Timor experienced the horrors of invasion by the Indonesian army, the story of the killing of the five television journalists known as the Balibo Five – a persistent subtext of that history – has found new life in the forthcoming feature film Balibo, directed by Arenafilm’s Robert Connolly. In reviewing Tony Maniaty’s related book, I must declare a vested interest: his book Shooting Balibo: Blood and Memory in East Timor has appeared on bookshelves two months earlier than a book of my own, on which that film is based.

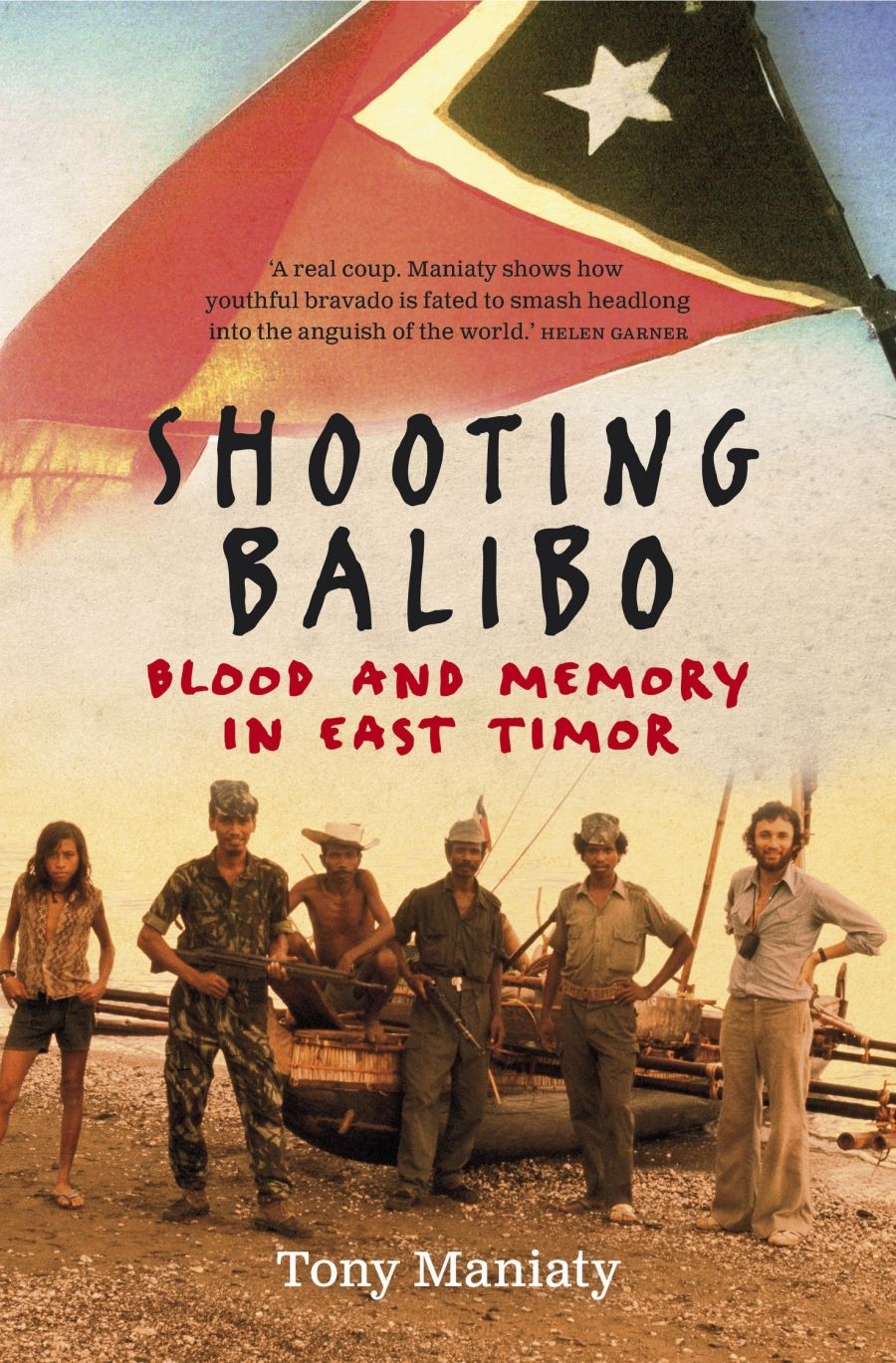

- Book 1 Title: Shooting Balibo

- Book 1 Subtitle: Blood and memory in East Timor

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking $32.95 pb, 311 pp

Maniaty’s book concerns both the making of the film, in which he is a character, and his brief stint in East Timor for the Australian Broadcasting Commission in 1975. I was competing with him then, too, as a freelance correspondent for Australian Associated Press and its parent company, Reuters. We were the only foreign journalists in Dili on 16 October 1975, when the Balibo Five perished during an Indonesian onslaught on the border towns of Maliana and Balibo. Together, we broke the story that the five reporters, from two Australian networks, were missing, believed dead. They were Greg Shackleton, Gary Cunningham, and Tony Stewart, of Channel Seven, and Channel 9’s Malcolm Rennie and Brian Peters – all aged in their twenties. The men were not, as is sometimes claimed, all Australians – Cunningham, the Seven cameraman, was a New Zealander, while Nine reporter Rennie and his cameraman, Peters, were British.

The evening of the sixteenth is imprinted on my mind. We were summoned unexpectedly from our hotel by Nicolau Lobato, leader of the nationalist Fretilin party, to the Marconi centre in downtown Dili, where he was with a group of Timorese soldiers fresh from the border. He told us that Balibo had been overrun by a large Indonesian force and that his soldiers said they had no idea of the fate of the men, who had been in the town at the time. He said he would open a shortwave radio line, then Dili’s only telecommunication link to the outside world, so that we could send our reports. I remember the light from the street lamp on the upturned faces of the young soldiers and the urgent dot-dash sound from the Timorese Marconi operator as he tapped out my story – headed INDON BLITZ – with unerring accuracy, although he understood not a word of it.

Shooting Balibo weaves Maniaty’s memories of those days with the story of his first return to East Timor since then, to accompany last year’s filming and to face his own ghosts. The bookfocuses on two themes: an examination of the complex personality of Greg Shackleton, the reporter who led the Seven team, which Maniaty believes may have contributed to the fatal sequence of events, and the question of his own perceived failings as a reporter. He depicts Shackleton as a driven, ambitious personality, possibly with suicidal tendencies, who dragged other members of his crew behind him.

Maniaty and the ABC crew had come under mortar fire at Balibo as Shackleton and his crew were heading out of Dili in the hope of observing military action there. Believing that they had been targeted by the Indonesian army, and that a larger attack would surely follow, they grabbed their equipment and retreated, heading back to Dili as fast as they could. On the way they were involved in a road accident, which increased the writer’s urgency to extricate himself from a situation that he felt he couldn’t handle. During this flight, their car passed that of the Channel Seven crew, where Maniaty has his first glimpse of Shackleton: ‘A tall and pale European male stood on its running board, bare-chested and in shorts – a taller, thinner and less resplendently dressed version of George C. Scott as General Patton standing on his Willys jeep.’ On Maniaty’s account, Shackleton asked what the situation was in Balibo, to which he replied that it was quite unsafe and advised him to turn back. He writes that, if anything, the warning had a contrary effect, and that ‘a visceral buzz of excitement ran through the Seven news crew, as though I had announced the start of full-scale war’. They rejected his warning and continued. On his return to Dili, Maniaty came across the Channel Nine team, which was anxious to catch up with the rival crew. Maniaty knew Rennie and resolved to stop him, but Rennie’s response was the same. ‘The last thing he wanted to hear were my lame protestations about battlefield danger,’ he writes. Early in the book, Maniaty observes:

For much of my adult life I’ve been accused of not being involved enough, of being too remote, too diplomatic, of being an Australian spy, of being a Communist, of sitting on the fence, of being a stooge for Canberra, of being for the Indonesians and the Americans, of being too close to the story, of abandoning the East Timorese in their hour of need, of cowardice.

In subsequent passages, it is clear that the last accusation haunts him most, invoking the possibility that he is still suffering from survivor’s guilt. After the Balibo shelling, he rang his newsroom boss, Fred Miles, to say that he was leaving. Miles replied, ‘Tony, a good correspondent stays on the job’, but Maniaty left anyway.

I was one of those who chose to stay. Perhaps we were driven by ambition or were a little mad or had personal motives, such as trying to test ourselves. In general, war is men’s business, and arguments around ‘courage’ or ‘cowardice’ are conducted in that limited framework. The reality is that courage under fire is little more than the ability to control the physical reflexes of fear, such as keeping the sphincter muscle tight and clenching one’s jaw to ensure silence (with that wonderful chemical adrenalin usually kicking in to boost performance). It cannot, in my view, be compared to the courage of one who, at a polite dinner party, chooses to break resolutely with her peers by refusing to accept an anti-Semitic remark, for example; that is much more difficult.

Every journalist has the right to choose whether they are prepared to be shot at or not without accusations of cowardice. From Maniaty’s account, it seems he wasn’t offered much of a choice by the ABC. He felt that if he didn’t accept the Timor assignment he would suffer professional prejudice. ‘I was a junior employee of a great organisation. Who was I to decide my own fate?’ he asks.

The writer’s contention that Shackleton’s character traits led him to drag his colleagues into danger is not supported by facts. Letters have survived that Peters and Cunningham wrote from Balibo to their families the day before they died. Clearly, they were willing participants, very aware of the danger they faced and weighing up their chances of getting the big story and then exiting successfully. They failed and died, but in turn became the big story. As Gough Whitlam’s collateral damage, they live on more than three decades later.

Shooting Balibo is essentially a memoir, with the strongly subjective flavour this implies, but it also claims to relate some facts of the Balibo story, which are frequently inaccurate. It is also marred by misspellings and the lack of an index, giving it the air of a book slapped together in a hurry.

Comments powered by CComment