- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

John Brack (1920–99) is one of the most remarkable of Australian painters, and a salient figure in the generation that included Arthur Boyd, Fred Williams, John Perceval, Leonard French, and John Olsen, of whom only two survive. Many viewers would see him as the imagination that made our suburbs viable as art; others have been in two minds about his clarity and perfectionism. Hard edges can make for tough responses.

- Book 1 Title: John Brack

- Book 1 Biblio: National Gallery of Victoria, $59.95 pb, 248 pp

The National Gallery of Victoria gave Brack a retrospective exhibition twenty-two years ago; now we have another, fuller display of his art and embodied thought (after closing on August 9, it will move to the Art Gallery of South Australia in October). With it, there comes a substantial catalogue, with no less than five essays, the first being a salutary wake-up call from his widow, Helen, who also paints as Helen Maudsley. She brooks no laziness from viewers of John’s oeuvre, and writes of ‘simultaneously different and incompatible meanings incorporated by the artist, available in time spent viewing’.

A retrospective show can review an artist’s career in different ways. Jeffrey Smart’s New South Wales retrospective (1999) weakened his achievement greatly, playing up mere repetition of a successful formula in his later paintings. But the Brack exhibition, like that of his sometime pupil Peter Booth, back in 2003, keeps on displaying the growth paths of a richly enquiring imagination, even when these appear disconcerting. There is the early work of the postwar period (Brack had served in the AIF), with its eloquently strong images; but also the lovely etchings and paintings of his four daughters, above all the masterly ‘Baby Drinking’; there is a world of jockeys and a demi-monde of reflective shop windows; the cakey wedding pictures and the psychological portraits; nudes in two phases, and the late pencil-scapes.

The latter pictures offended the Melbourne Age’s reviewer, Robert Nelson, whose largely negative account of the show also fell heavily on Brack’s nudes, which he dubbed ‘ugly exsanguinated things’. Maybe Nelson should have looked longer and harder, given the complex codes of Brack’s pictorial diction. Or perhaps he was born into a more sentimental generation.

My first encounters with Brack’s paintings were at the long-vanished Peter Bray Gallery, in Melbourne. These pictures were arresting because of their odd austerity. Whether of shop interiors or empty-feeling suburban subdivisions, they played on my attention immediately; they were so far from the malerisch expressionism and the douce landscapery that seemed to be the local norm back then. Their subject matter was utterly unclichéd. Chris McAuliffe writes in this catalogue of how Brack’s early pictures sat in distinctive suburbia yet were ‘driven by a process of elimination, as if suggesting what painting could no longer be’.

Heads and faces were another matter, with their harsh insistence of line over modelling. It was in some of these early paintings and sketches that hostile viewers saw too much of fashionable Bernard Buffet’s heavy hand and light mind. But the Australian was deeply rooted in the dailiness of common life: the Human Condition, as he put it. Moreover, he was not only a suburbanite but also an intellectual by nature, feeling kinship with T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden and Henry James. Paradox ran quietly in his veins. Still, it could be said that his Eliotic impersonality could appear cold or harsh at times in the early depictions of urban man and woman.

Long ago, Brack and I gave a joint lecture at the NGV. It was to VCE students, or was the year still called Matric in those days? One young romantic asked Brack what it was like starting work as an artist in the mornings. He replied, in his rather nasal voice: ‘I go out there, look around and think, oh yes, another eight hours work.’ I am not at all sure what the students made of this reply, but Robert Rooney once installed Brack in the ranks of the Cool, a category that was becoming cool at the time.

At lunch in Italianate Carlton on another day, John told me about being given the Macmillan standard edition of Henry James’s novels during World War II. On his way to camp in Western Australia, he found himself with a bored fellow soldier who had nothing to read. All John had with him was one of the later novels, so that his only courteous solution was to tear out each page, once he had read both sides. ‘And you know,’ he told me, ‘each time he read a new page he said the same thing.’ ‘What was it?’ I asked. ‘Shit!’ he replied.

These occasions, along with many others, are called to mind by the array of his pictures, the oeuvre if you like, in the present NGV exhibition, and again by their evocation in the large, genuinely informative catalogue, which the contributors approach from different angles around Kirsty Grant, curator of the show; and are augmented by a checklist and bibliography. It is certainly a rich catalogue.

Grant, in her valuable essay at the heart of this book, writes of the early work: ‘Brack’s desire for the human subjects in his paintings to be based on real people rather than invented ciphers coincided with his ability to observe and record the details of physical appearance in such a way that he also captured idiosyncrasies of personality.’ Perhaps the sinuous length of that sentence stands for the struggle we all have when translating the language of pictures into a verbal construction: not least with Brack’s distinctive accent, his restlessness.

Brack was never all that easy to pin down, but, among many other observations, Grant is certainly right in saying that ‘[t]he enduring quality of Brack’s suburban images rests on his avoidance of thinly disguised snobbery’. The painter may have been an intellectual, but he was also a willing inhabitant of suburbia, an imaginative recorder of ‘what lies nearest to hand’. Gymnasiums and primary school playgrounds, ballroom dancing and shopfronts were all aspects of the normal world to him, however much he selected, hyperbolised and refined what he saw.

By whose projection do we affect to register the world on a plane surface? Is the artist a kind of god? Perhaps all artists are moralists at some level, which is certainly what Helen Brack’s introductory essay would enforce.

For all his recognisable aesthetic DNA, Brack was a restless artist. Over the years, between his acid nudes and the sensuous nudes with vertiginous Persian rugs, his visual preoccupations kept zigzagging. The early 1960s, just after the divisive ‘Antipodeans’ Exhibition, give us Brack’s oddball wedding paintings, with figures cake-sliced out of deep impasto. Most daring among these is ‘The Golden Embrace’, an abstraction in which ‘the subject is reduced to a series of glowing fleshy forms pressed together’.

Soon after these, the painter waltzed off on a very different tack. In a lyrical whirl of alizarin, rose madder, pink and black, ballroom dancers are grandly swept across the picture plane. The movements are elegant, the colours a puzzle. As Ronald Millar complained at the time, ‘there are so many almost irreconcilable reds in the large pictures that the technical problems of relating them are extremely difficult’. Yes, these are odi et amo paintings of some grandeur. Are these, for us, ‘descriptions of human development’, as they were seemingly intended? Beats me. At this point, I might do well to turn back to the redoubtable Susan Sontag and her essay ‘Against Interpretation’ (1966). Still, these visual readings of dance are so compelling as to be dynamic haptic, if you like, to use an art-speak term that went out even before these pictures were created. They are charged with ebullient musicality.

But Brack’s highly original portraits are something else again, many of them framed metaphorically and formally in such a way as to body forth psychological truths. Thus, John Perceval’s withered leg partly echoes the terra cotta angels ranged along his shelf, while early Fred Williams is limned in classic formal stillness, contrasting with his discernible physical discomfort, twenty-one years later. The Barry Humphries portrait as Edna Everage is iconic, of course, with its amazing range of ‘female’ colours and flaunted pink gloves stretching out across the picture’s horizontal format.

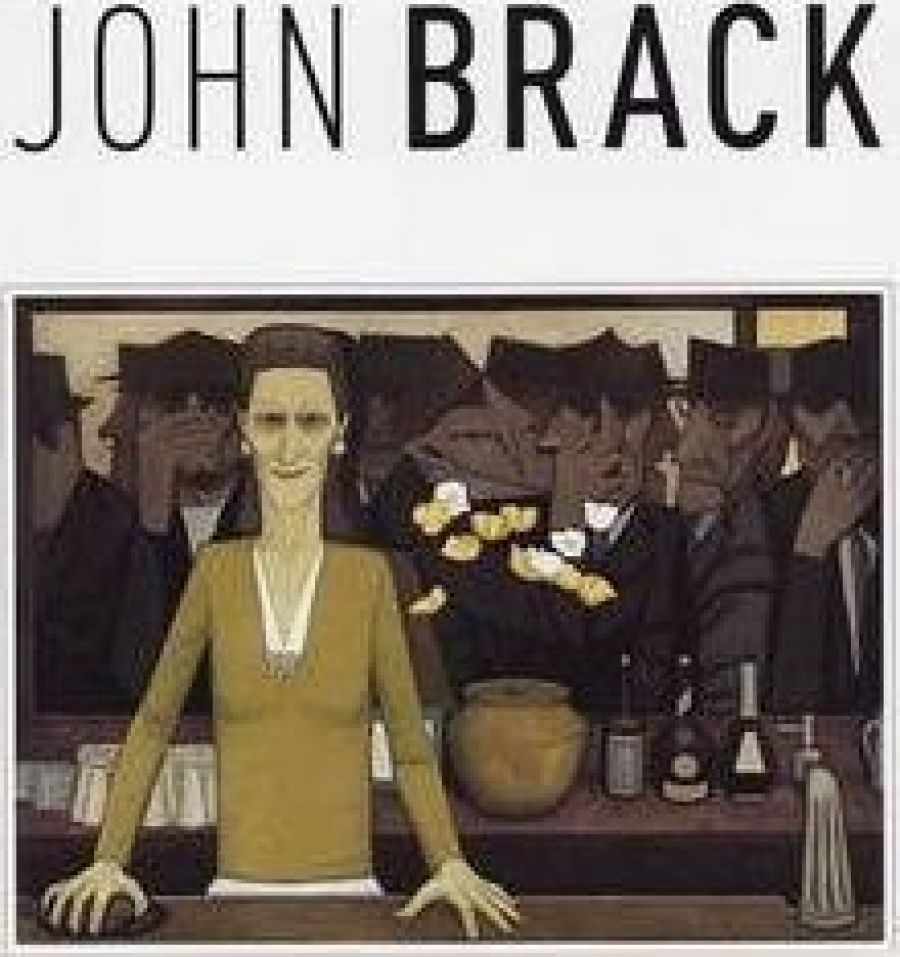

As recent news items along with frequent reproductions will have made clear, ‘The Bar’ and ‘5 O’Clock Collins Street’ are Brack’s iconic works for the Melbourne public, the latter painting often crudely taken for a complete distillation of the now-despised 1950s. There were whoops of triumph when the NGV finally acquired ‘The Bar’, a recension of Manet’s famous Bar at the Folies-Bergère, and enabled these two favourites to hang side by side. Indeed, they put me in mind of Dr Johnson’s remark about ‘sentiments to which every bosom returns an echo’.

One of Brack’s most compelling paintings is surely The Battle (1981–83), made up from swirling tides of virtual geometry. This is an amazing work, monumental if you like. It represents, with pencils and pens for troops, the last stage of the Battle of Waterloo. The British in red and the French in blue are locked in conflict, as though we were looking at a battle map with Napoleon’s troops trying to break through from the south; from the north-east pours in the bulk of Blücher’s brown Prussian forces. The pens and pencils, highlighted along one side, arrest one as hypnotically as stripes in a Bridget Riley canvas. At first glance they look identically painted, but along the line of battle dark shadows deepen the red to magenta, the blue to navy even the highlights becoming obscure. A similar grimness shadows the fallen soldiers.

Here, geometrical complexity is so extreme that it comes to seem organic. A passionate swirling drama emerges from the gestalt, restraint organising excitement. No wonder Helen Brack calls it ‘a picture of human self-annihilation’; her husband had said that ‘people have a subterranean passion for apocalypse’.

Brack also knew that such passion had to be understood and then developed by classical rules, or, if you like, by the meanings that are encoded in the whole history of Western painting. Order is not earned easily.

Comments powered by CComment