- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

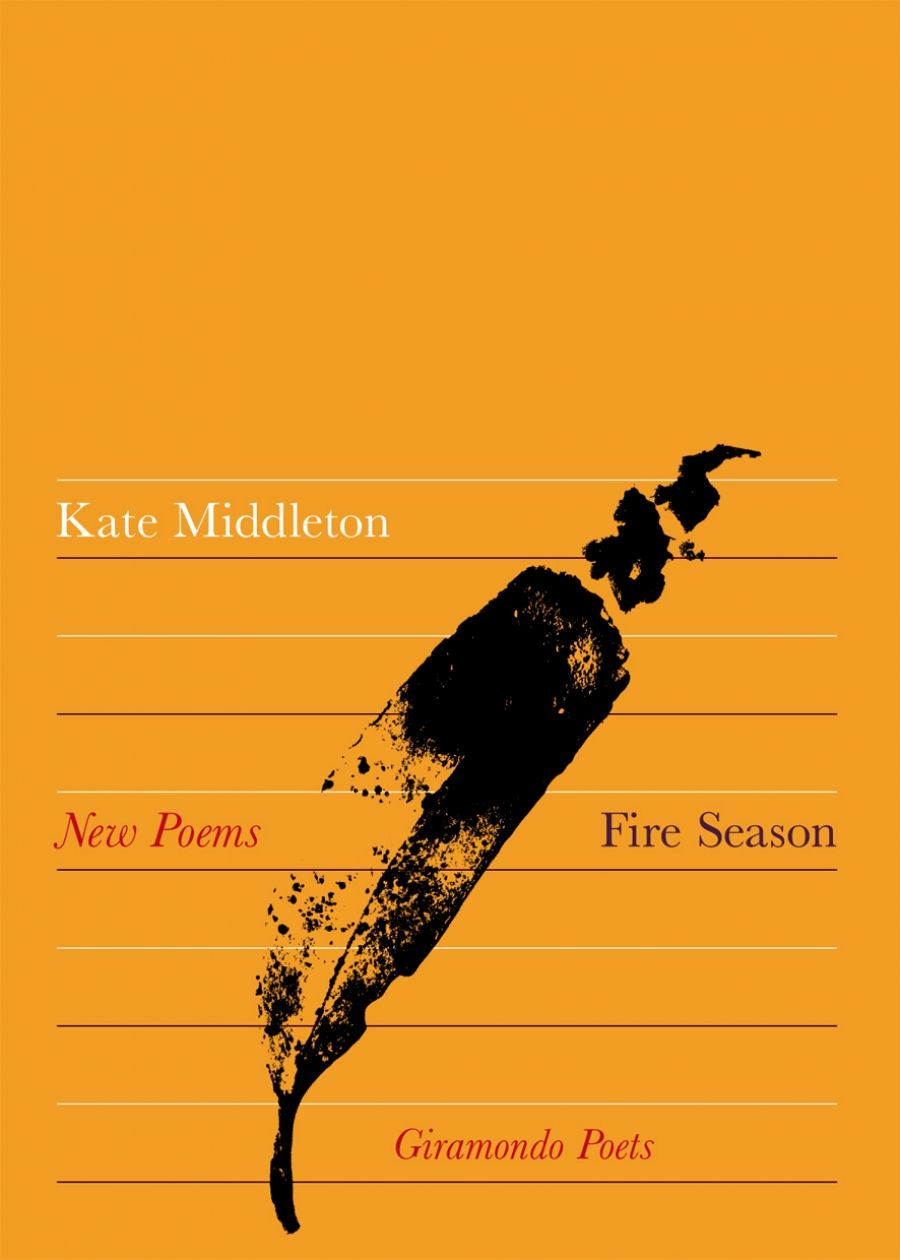

Kate Middleton’s accomplished first book, Fire Season, begins with ‘Autobiography’, where the child kicks against the perceived constraints and ambiguities of her sex: she could ‘make a half-decent boy’ only if the books she read were ‘full enough of war / or gunrunners, or treasure, or spies, or spoils / of piracy. No, I didn’t know how to hold a hammer.’ Middleton constructs a version of self defined by negatives: the narrator was not a ‘boy’, but does not explain why she sees ‘boy’ as the norm or as a preferred sex. Much of Fire Season explores some historical and mythical women, often in light of this shadowy definition (‘You once said // the visible and the invisible imply each other’, ‘Essay on Absence – Journal (with Judy Garland)’). In particular, Middleton invokes several movie stars – Lana Turner, Barbara Stanwyck, Doris Day, Clara Bow, Lauren Bacall, as well as Judy Garland – measuring her distance from these fabled figures, as well as investigating them as alternative lives.

- Book 1 Title: Fire Season

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo $22 pb, 96 pp

Other mythical or literary women are Scheherazade, Desdemona, Leda, Penelope, Sleeping Beauty – all defined, even negated, by their romantic relationships, famed as passive recipients of men’s actions. But Middleton also subverts that tattered dichotomy. Scheherazade is made by art; her inventiveness endlessly delays her death – ‘Sleep, as though // there were no sword between us’ (‘Scheherazade’s Nights’). The opening lines of ‘Penelope on the Night of Odysseus’ Homecoming’ – ‘There is a rumour of a golden realm, / an ocean both pacific and terribly blue …’ recall Keats’s ‘On First looking into Chapman’s Homer’ (‘Much have I travelled in the realms of gold’), a reminder that the fluency in Middleton’s work is often classical.

Another theme is travel, with poems covering the experience of learning Italian in Italy, and temporarily lacking language: ‘plastic spoons and empty sugar packets – the refuse / of the new Grand Tour’(‘Guigno, Firenze’). Many poems are dedicated to, or inspired by, other artists. All of these either overtly or implicitly ruminate on the possibilities of communication and representation in language and in art. One of the best poems in Fire Season is ‘Two Minotaurs’, the first part of which won the 2006 Bruce Dawe Poetry Award. Here, Middleton employs Dante’s terza rima with great assurance:

… Raphael sainted

by posterity, a Big Kahuna in the history of art

beatified by punters, his cherubs barely tainted

by their appearance on tacky love notes that start

and end disastrous affairs …

… The footnotes bullishly reveal the following –

that ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ mingle in ‘real life’ that fur

and flesh do tangle, and this walloing

monster is nonetheless still myth. Watch

that foot step through the ice. Watch the facts hollowing.

Middleton, like Picasso, identifies the artist with the minotaur – the untamed centre of the labyrinth. Her rhymes are cleverly unobtrusive, with lines varying in length, which makes this poem feel less formal. Middleton’s poems always follow their own internal rhythms and carillon sounds, sometimes repeating a phrase throughout as in ‘The First Cloud’, inspired by William Orchardson’s painting of that name. This begins and ends ‘Your tears are like a law laid down … // The promises carried in the lick / of your whisper have come to nothing. // The first cloud appeared in the midst / of richness. Write that down. To // remember. Your tears are like the drop // of the chandelier. Colourless.’ In ‘Desdemona’, Othello’s aching plaint ‘Put out the light’ is wrung out four times, and then a fifth time with the phrase reduced to vowel sounds – ‘Put out the ligh t- // Oo – ou – I –’. These renowned women are captured at decisive moments. Occasionally, there are echoes of American poet Susan Howe’s engagements with historical characters.

In ‘Essay on Erasure (with Clara Bow)’, Middleton uses crossed-out words to emphasise the silent film star’s dilemma. These words seem to disintegrate as soon as they are written, mimicking Bow’s horror of the newly installed microphones. Erasure and absence are recurring themes in Fire Season, emphasising the idea in ‘Autobiography’ that negation can be a form of definition.

The longer poems later in the book, the ten-part ‘Water (The Poem of Your Leaving)’ – which again takes up a changed Penelope and the travelling Odysseus (‘Penelope not really sorry – / she has grown accustomed to solitude’) – and another inspired by American earthworks artist Robert Smithson, ‘Autobiography (with Robert Smithson)’ are slightly more tentative and exploratory.

The book finishes with the gently bleak ‘Last Poem’, where a relationship ends (‘no symphony, no cherish’), again returning to a theme of elegiac absence and lack. Kate Middleton’s Fire Season is an intelligent début.

Comments powered by CComment