- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Selected Writing

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

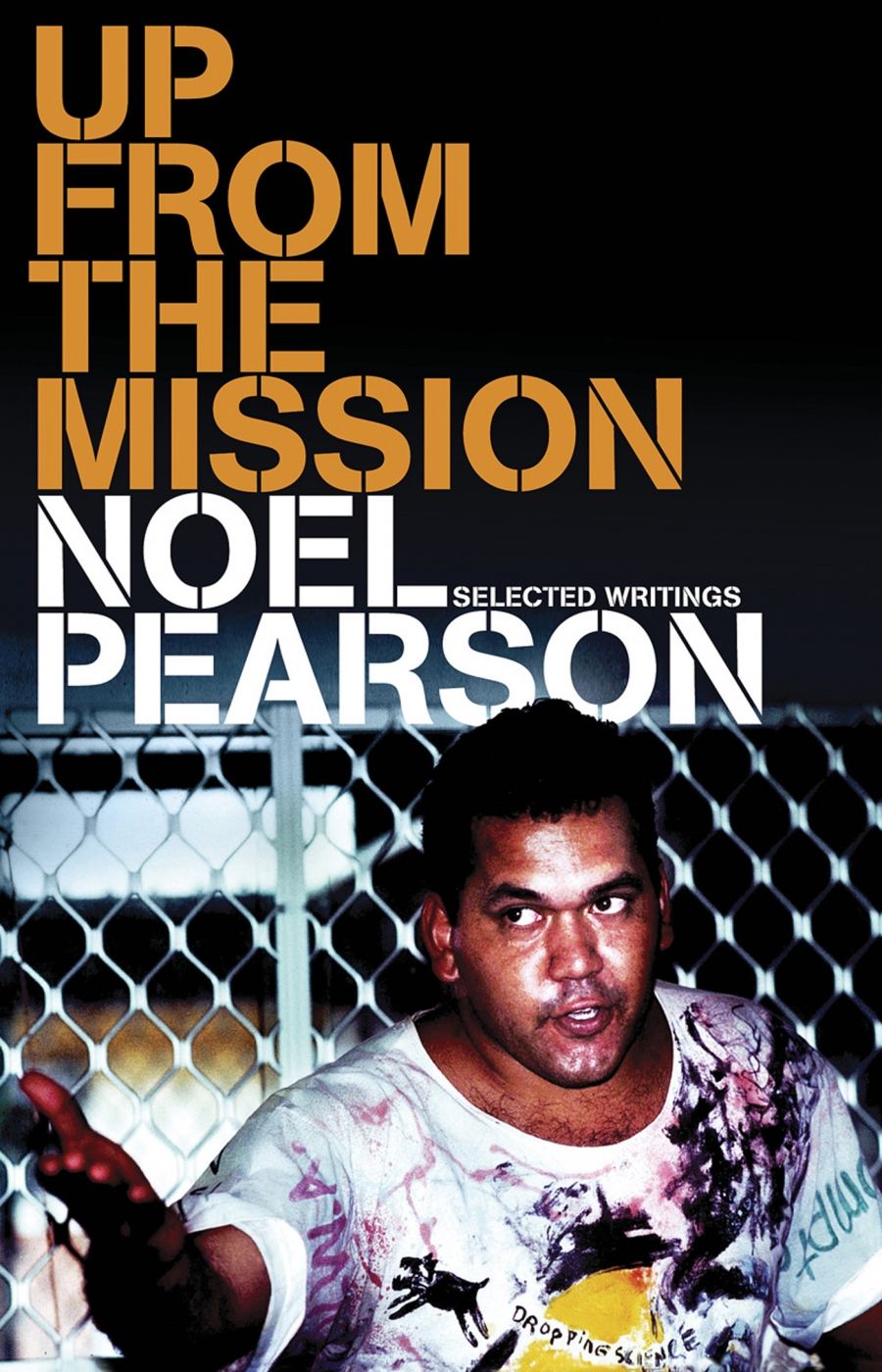

Up from the Mission is a powerhouse of a book. One would expect no less from Noel Pearson. This collection of thirty-eight essays combines to provide multiple overarching narratives: Pearson’s personal trajectory from the mission on Cape York, where he grew up; his intellectual development; and his political efforts at regional and national levels to redevelop Cape York communities and to influence the nation. The writings date from 1987 to 2009, from his first essay as a radical graduate student to his latest pronouncements.

- Book 1 Title: Up from the Mission

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected writings

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc, $34.95 pb, 400 pp

Up from the Mission begins with a brief introduction in which Pearson reflects on his problematic but ultimately close personal relationship with John Howard. Pearson outlines his policy suggestions to the prime minister in the lead-up to the 2007 federal election. These cover reconciliation, the republic and the transformation of Australia from a welfare to an opportunity state. From the outset, Pearson identifies three interlinked projects: the rehabilitation of dysfunctional Cape York indigenous communities; a policy agenda for addressing the ‘Aboriginal problem’; and the transformation of Australian society to effect a proper accommodation with its first peoples.

The collection is divided into five parts. ‘The Mission’, comprising four brief pieces, tells us something of Pearson’s humble Hope Vale origins. Interestingly, as early as in 1987, Pearson raises concerns about the loss of basic social norms and about problems with alcohol, social irresponsibility and victimhood.

‘Fighting Old Enemies’ traces Pearson’s battles as an activist lawyer for land justice following the Mabo High Court judgment of 1992. He discusses native title law, and its depressing statutory and judicial dilution. It was during the campaign for land rights that Pearson rose to national prominence and that the seeds of his understandable frustration with any approach that gives pre-eminent emphasis to the rights agenda were sown. Here, too, we encounter Pearson’s contempt for Howard’s dishonesty in dealing with native title. It says a great deal for Pearson’s character and leadership that he was able to pick himself up and appreciate the need to negotiate with people from the right.

‘Challenging Old Friends’ and ‘The Quest for a Radical Centre’ trace Pearson’s epiphanic realisation that progressive approaches alone will not address deeply entrenched problems of Aboriginal disadvantage. He shifts his attention to individualism and personal responsibility. This change is characterised by a retreat from the national to the regional; Pearson charts the Cape York project from a mere idea to a fully funded program. Rights and responsibilities, progressive and conservative, left and right are conceived as dialectically related, not mutually exclusive, in ‘the radical centre’.

‘Our Place in the Nation’ consists mainly of recent Op-Eds that are more forward-looking and philosophical, marking a re-engagement with the national scene. It concludes with Pearson’s blunt views about Kevin Rudd’s political opportunism and volte-face about constitutional reform on the eve of the 2007 election; and with Pearson’s nuanced reflections on the formal parliamentary Apology of February 2008. Pearson consistently remains above party politics but also possesses an extraordinary capacity to re-establish close working relations with the most powerful, despite ideological differences.

The most moving and provocative essay in the volume is ‘Hope Vale Lost’, originally published in 2007. Pearson’s return to his home community leaves him shocked and despondent. He concludes that elements of ‘Aboriginal culture’ and ‘self determination’ have combined in a deadly cocktail. He speaks of a multifaceted set of destructive behaviours, including rape, substance abuse, physical violence and homicide. In this extreme case, the community of Hope Vale has lost the basic social norms, in part because of inactivity and access to passive welfare, but also due to alcohol abuse. Geographical remoteness and an absence of leadership have allowed such dysfunction to be hidden from public scrutiny.

Pearson is candid about his lessons from Paul Keating with regard to conviction politics; from development economist Amartya Sen about choice and capabilities; from conservative black American Selby Steele, who argues that ‘black responsibility is the greatest power available to blacks’; and from controversial Swedish psychiatrist Nils Bejerot, for his ‘alcohol addiction as a disease’ theory. Most important are the lessons that Pearson draws from his own life, the educational tool kit that makes him as comfortable in the bush as in The Lodge.

For nearly a decade, Pearson has driven a project of radical cultural redevelopment to restructure the lives of people on Cape York. This project is modelled on self-respect, individual responsibility and greater engagement with the mainstream, facilitated by educational capabilities. Pearson wants to give the market a more prominent role on the Cape, in keeping with neo-liberal values predicated on individualism, wealth accumulation and risk-taking.

Pearson has been successful in sequestering considerable state support for the Cape York project. This includes welfare reform to ensure proper behaviour; the restriction of alcohol; greater educational and employment opportunities; assistance with family income management; support for the Cape York Institute of Policy and Leadership that has been his headquarters; and changes to Commonwealth and Queensland laws to establish a Family Responsibilities Commission. These major institutional reforms attest to Pearson’s drive and influence. But will the reforms work, and is the model transportable?

On the former, it is too soon to judge. Unfortunately, the reform experiment for greater economic integration coincided with the global economic crisis of 2008–09. The latter question is far more complicated. Here, Pearson clashes with other indigenous leaders and with many public intellectuals, for a variety of reasons: scepticism that the systemic problems on the Cape are replicated elsewhere; concerns about potential human rights breaches; and frustration at Pearson’s almost monopolistic influence on policy, especially since the demise of ATSIC. A deeply held indigenous protocol demands that one does not talk for other people’s country; Pearson is seen as transgressing this, especially in his lending of crucial moral authority to the paternalistic Northern Territory National Emergency Intervention. Pearson might counter that by grasping ‘the burden of responsibility’ he has chartered a different, less Draconian and more productive policy course for Cape York.

A number of these essays are reprints; more than half first appeared as Op-Eds in The Australian. About a dozen are thoughtful lectures and speeches that were either unpublished or are difficult to source. Having these pieces in a single, well-indexed book is very useful. Some resistance is to be expected, especially from critics of Pearson’s combative and hubristic personal style; he has become such an omnipresent figure in Australian public life and in the media. But any impatience or prejudice should not dampen interest in this thought-provoking book.

Recently, Pearson took leave from his directorship of the Cape York Institute to fight for the right of Aboriginal land owners on Cape York to enjoy full property rights in natural resources and to achieve equitable participation in the market economy. The dichotomy between rights and responsibilities might not be as clear-cut as Pearson has suggested. Similarly, one might ask how many indigenous Australians yearn to embrace individualism and market values over group rights and kin-based economies. What is the appropriate balance between state enabling and individual or community agency in helping people overcome severe disadvantage? Can we be confident that migration from home communities and individualism can sit comfortably with an ongoing attachment to community and country? Personal success and a complex political identity have served Noel Pearson well. For others, will it be a realistic choice, or an aspiration?

Comments powered by CComment