- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Subheading: Ruth Park's trilogy of want and human spirit

- Custom Article Title: Bitter Fruit

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: Bitter Fruit

- Article Subtitle: Ruth Park's trilogy of want and human spirit

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

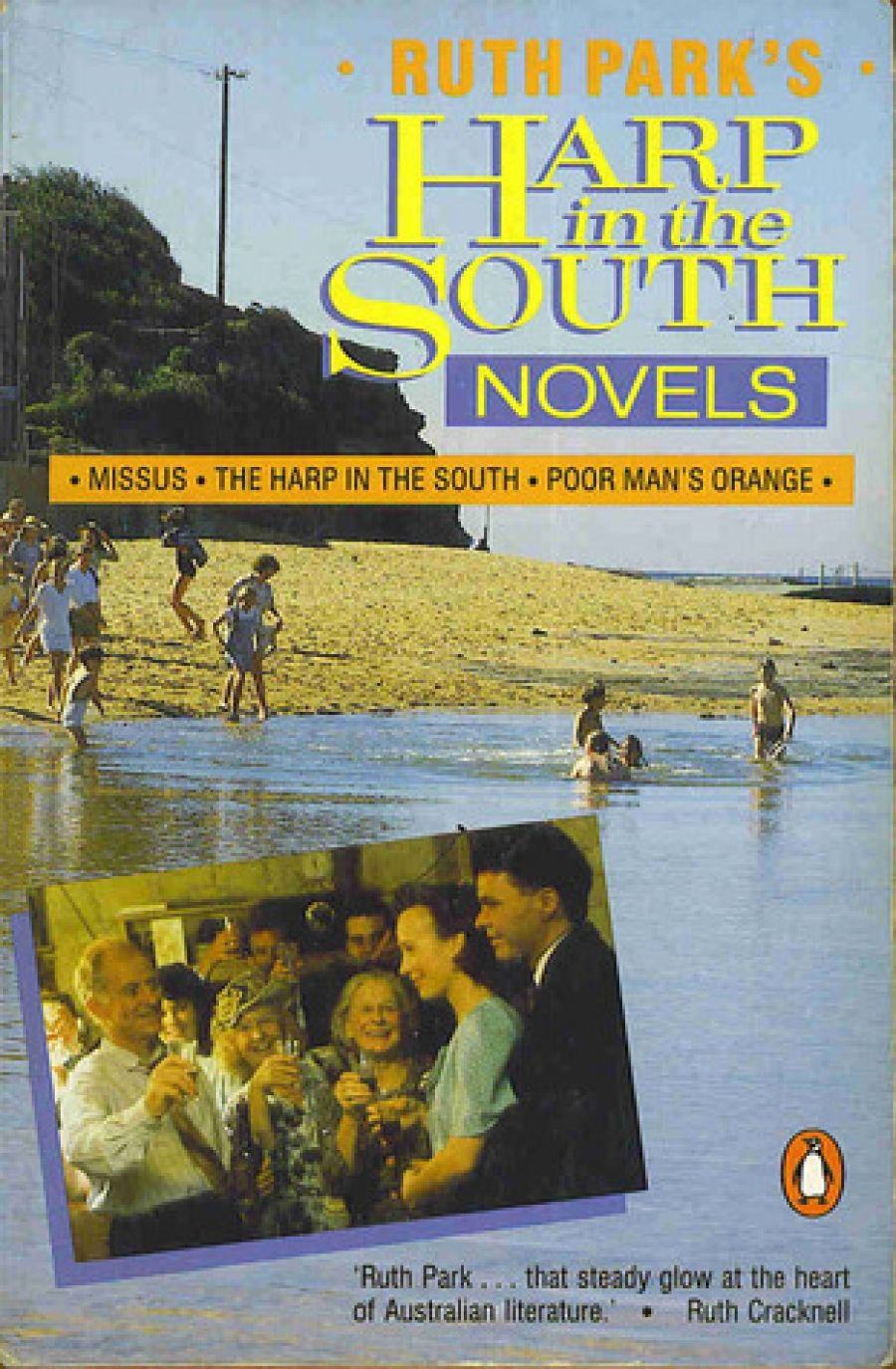

The reissue in one volume of three of Ruth Park’s much-loved novels The Harp in the South (1948), its sequel Poor Man’s Orange (1949), and the prequel Missus (1985) is welcome. The trilogy completes the family saga, taking the Darcy family from its emigrant beginnings in the dusty little outback towns where Hughie and Margaret meet and marry, to their life in the urban jungle of Surry Hills, then for-ward to the 1950s when the next generation prepares to leave the slums for the imagined freedom of the bush. These are Australian classics, but classics of the vernacular, of the ordinary people. They should never be allowed to disappear from public consciousness.

Park’s writing over the last six decades has been a steady presence, a ‘glow at the heart of Australian literature’, according to Ruth Cracknell. Park is one of Australia’s most prolific writers, with a vast array of novels, books for young people, plays and short stories to her credit. She has written three autobiographies (one with her husband D’Arcy Niland), a biography of Les Darcy (with Rafe Champion), decades of radio, film and television scripts, and much, much more. The ‘Muddle-headed Wombat’ series, for instance, ran on the ABC Radio Children’s Session from 1957 to 1971. Park has won many distinctions, including the Miles Franklin Award for Swords and Crowns and Rings (1977). In 1987 she was made a Member of the Order of Australia, and in 2008 was awarded the Dromkeen Medal for her services to children’s literature.

In A Fence around the Cuckoo (1992), the first volume of her autobiography, Park recalls her solitary childhood in a ‘numinous landscape’, the majestic forests of New Zealand around the small town of Te Kuiti. She lived through the Great Depression, particularly severe in New Zealand, and this no doubt contributed to her understanding of both poverty and the fortitude of the poor. She always had a strong sense of vocation as a writer. Having fought hard for an education, she worked her way up the journalistic ladder from proofreader on the Auckland Star to editor of its children’s page. Coming to Sydney in 1942, Park married the writer D’Arcy Niland (1919–67) and astonished the literary world with her first novel, The Harp in the South. It was written, she tells us in Fishing in the Styx (1993), in great haste on a kitchen table in New Zealand after her two children had gone to sleep. This won the inaugural Sydney Morning Herald novel competition in 1946, the prize an unimaginable £2000. The subsequent newspaper serialisation created a furore. While the novel delighted the majority of its readers, its raw depiction of the poverty, violence and filthy living conditions in Surry Hills aroused hostility among the wowsers and those who preferred to turn a blind eye. A priest denounced the novel from the pulpit.

But there was more to it: the author was so young and beautiful, yet seemed to know so much about child abuse, abortion and prostitution, and was not afraid to write about them. Though Angus & Robertson published The Harp with some reluctance, the novel established Park’s international reputation, and it has never been out of print in Australia. Its realistic portrayal of the Sydney slums almost certainly contributed to the New South Wales government’s decision to demolish them and rehouse their inhabitants.

I am old enough to remember not only the fierce debate about The Harp but also the great joy with which each episode was received. Also, I am Irish enough to appreciate the language, as rich and over-plummed as Hughie’s legendary Christmas pudding: ‘dark as midnight and rich as Persia, and containing so many dates, prunes, cherries, sultanas and currants’ that you ‘couldn’t spit between them’. This is the way my father talked, and my Irish grandmother, too, who once threatened to ‘nail me into the ground like a tack’ for ‘worry-ing the soul-case’ out of her. This is the richly metaphoric language of people for whom language has not yet been diluted, not yet become bland. As The Harp puts it: ‘The Irish in these people was like an old song, remembered only by the blood that ran deep and melancholy in veins for two generations Australian.’

The Harp in the South and Poor Man’s Orange can be read as a continuous narrative. Their message is simple and heart-warming: the persistence of love, goodness and humour in a brutal world. The characters, created with great compassion for their failings, are vividly alive: the ever-loving but slovenly Mumma; the defiantly alcoholic Hughie; acid-tongued Grandma; Roie and Dolour growing up with ‘sweet timid yearnings for the security and contentment of love’.

Behind them is a richly varied supporting cast: the part-Aboriginal Charlie, who has never known a home; the Orangeman Patrick Diamond, who decides at one stage to become a priest; Lick Jimmy the fruiterer; the acidic Miss Sheily who settles for a most unlikely marriage; and many others. We, the readers, suffer with them, laugh and cry with them, and get to know them as well as our own neighbours. These people often stumble and fall short, are often vulgar, but are never short of a loving word or, more often, an abrasive tirade that would ‘strip the hide off’ its target.

Disaster is never far away. A much-loved six-year-old son simply disappears from the front street. His mother searches for him, breaking her heart for a decade, then realises in a moment of blessed release that he is surely dead and out of harm’s way at last. A rat as big as a kitten chews a baby’s face, then attacks its pregnant mother. Perhaps Roie’s heroic battle with the rat is responsible for her death a couple of days later; perhaps it is due to an earlier episode where, just for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, she was brutally bashed and kicked by the drunken crew of a Dutch ship, rampaging through the slums.

This is a dog-eat-dog world where the faces of evil are endlessly varied and endlessly fascinating: the prostitutes and their pimps; the stand-over men and the profiteering landlords; the madams like Delia Stock who recruit the hopeless young girls; the callow youths whose one aim is to ‘score’; and the abortionists who prey upon the girls’ misfortune.

Set against this is the idealised love of Roie and Charlie, their marriage and the birth of their baby, Moira, and Mumma’s ever-forgiving love for Hughie:

He was tired and clumpy and middle-aged, and he smelt of port and sausages and cheap shaving-soap, but she loved him as she had never loved him before [...] ‘I was thinking of how lucky we are,’ whispered Mumma.

Poor Man’s Orange swings the balance the other way with the death of Roie, the lapse into apathy of Charlie and the neglect of their children. The ‘old, simple, warm contentment’ of the house in Plymouth Street is gone. Hughie makes a fool of himself, falling in love with a young prostitute and, brutally bashed by her pimp, has to face his decline into old age and futility. He stumbles up the street in the dark, ‘with the wind blowing dead leaves about his feet, and in his heart the helpless, defenseless despair that comes after drunkenness’. All his life he had sought what his forefathers had sought: ‘The rainbow that never ended anywhere, the unbeatable conviction that somewhere, sometime, things would be better without his bothering his head to make them so.’

The poor man’s orange of the title, then, is the bitter fruit of winter, appropriate for a people who know in their hearts that they must always settle for less. Dolour, cheated of an education and in love with her dead sister’s husband, accepts that the winter orange, with its ‘bitter rind, its paler flesh, and its stinging, exultant, unforgettable tang’, would of necessity be hers. But she accepts it; it is the price of love for a woman at this time, in this place. Dolour, at least, has achieved maturity and responsibility.

The completion of the trilogy with Missus (written some forty years after the other two novels, but placed first) establishes the chronology and reinforces the seasonal pattern. This is the dubious springtime of Hughie and Margaret’s courtship. As well, Missus expands the scene to include the outback: the shearing sheds, the grog shops, the cop shops, the desperate little towns. Poverty, violence and injustice are everywhere; they are not confined to the city.

The first five pages, devoted to Hughie’s family history, set the tone. A gravel carter brings his bride, Frances, a timid governess from a northern station, to his dilapidated shack. Hugh is her second baby; the first was stillborn. When her neighbour shoots Frances’s beloved fox terrier, her husband, thinking to comfort her, spends all his savings on a taxidermist. The stuffed dog is cold and stiff, frozen in an artificial pose, ‘sitting on her hind legs, begging, her dainty white paws turned down’. Her hide is ‘as pure as snow’, her eyes ‘as dovelike as in life’. Confronted by this horrible sight, Frances, not surprisingly, plummets into insanity.

The next child, born deformed, is rejected by his father. Hughie grows up looking after his crippled brother, protecting his insane mother and fighting off his father. When he is ten, Frances drowns herself in the nearest waterhole. Understandably, Hughie grows up to be a knockabout, heavy-drinking, irresponsible youth. This catalogue of rural horrors is, I’m sorry to say, melodrama rather than tragedy. And the characters in Missus save for Hughie and Margaret, towards the end of the novel fail to engage the reader.

Meanwhile, when the buxom, blue-eyed Margaret tumbles from a merry-go-round at the fair into Hughie’s arms, she becomes a willing victim. She wears him down with her adoration and pays his bills until he marries her and she becomes the Missus of the title and the Mumma of The Harp in the South and Poor Man’s Orange. What it means to be a ‘Missus’ will become clear in the course of the trilogy: hers will be a lifetime of love and devotion, hardship and self-sacrifice.

How successfully does The Harp in the South Novels stitch the three works together? Long-time readers, passionate about The Harp and Poor Man’s Orange, might find Missus too rambling, discursive and all too often melodramatic. They will be forgiving, but first-time readers will probably find it a difficult entry into the saga.

Comments powered by CComment