- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Subheading: Jock Given reviews 'Treason on the Airwaves' by Judith Keene

- Custom Article Title: Jock Given reviews 'Treason on the Airwaves' by Judith Keene

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cypress wars

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘It is high time for me to put an end to your sitting in this place,’ declared Oliver Cromwell to the Rump Parliament in April 1653. ‘Ye are a factious crew, and enemies to all good government … In the name of God, go!’

Leo Amery, a Conservative backbencher, brought Cromwell’s final six words into the House of Commons on 7 May 1940. He was unsure whether he would use them in the debate over Norway, where British and French forces were withdrawing from the first major land confrontation of the war. Colonial Secretary in the Conservative governments of the 1920s, Amery was a passionate advocate for the British Empire and strongly anti-communist. In the 1930s he became a tough critic of his own party’s appeasement of Nazi Germany. Speaking late in the debate, Amery felt the House was with him, and he ended his speech as Cromwell had done. Neville Chamberlain survived the division, but not the collapse in support from a fifth of his backbench, galvanised by Amery and others.

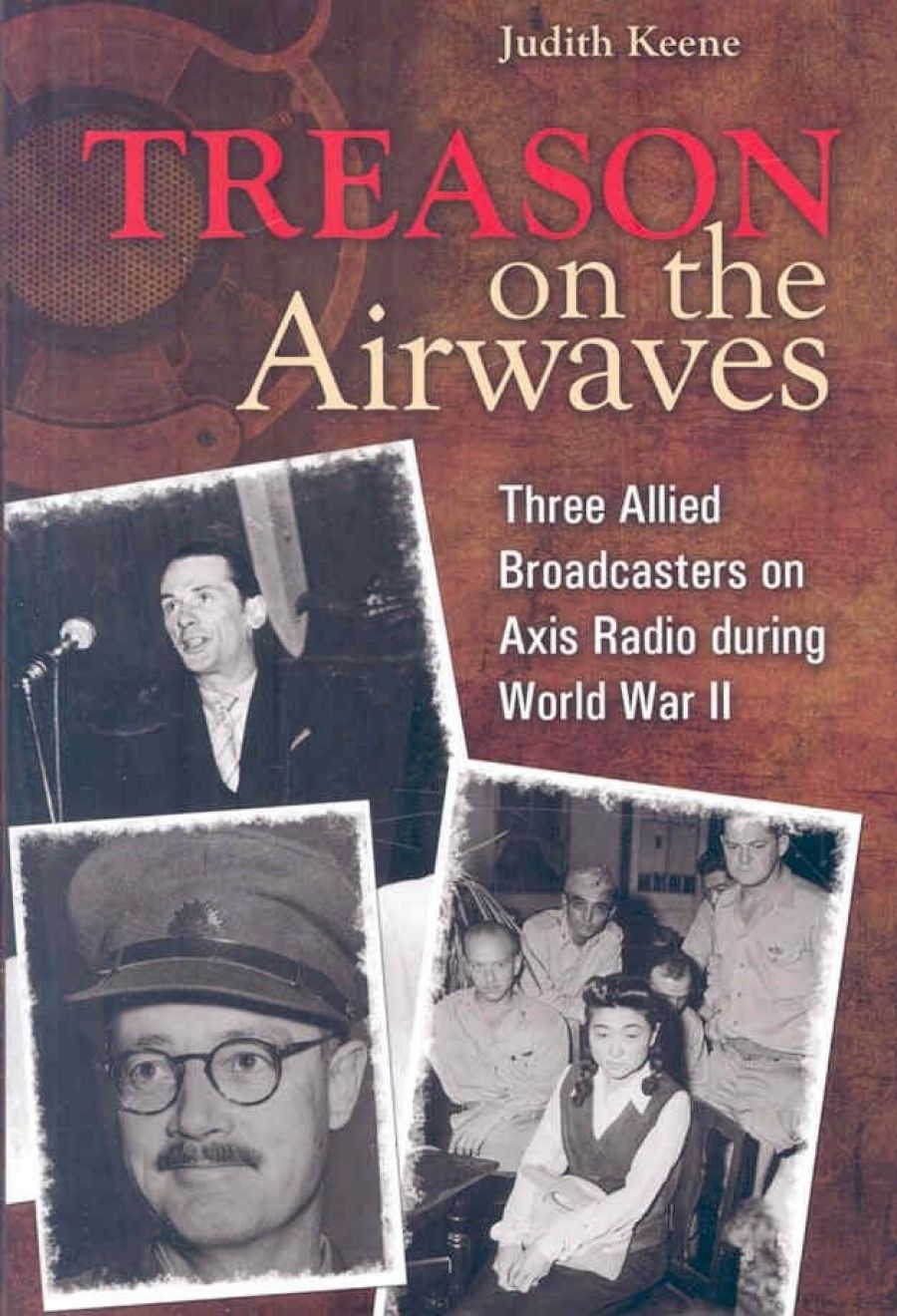

- Book 1 Title: Treason on the Airwaves

- Book 1 Subtitle: Three Allied broadcasters on Axis radio during World War II

- Book 1 Biblio: Praeger Publishers, $79.85 hb, 240 pp

Treason was what many of Chamberlain’s supporters thought the rebels had committed. When Churchill entered the House of Commons to deliver his first speech as prime minister a few days later – ‘What is our aim? Victory at all costs and in spite of all terrors; victory, however long and hard the road may be’ – most of the Tory backbenchers sat silently. They cheered Chamberlain, who followed Churchill into the chamber, though they joined the unanimous vote of confidence in the new leader of the all-party war government.

Five years later, after Amery lost his seat in the election that put Churchill out of office two months after VE Day, his elder son John was hanged in Wandsworth Prison. The crime was treason – not the ‘petty treason’ of one who murders a person owed loyalty, but the ‘high treason’ of a citizen who wages war on his own monarch or gives comfort to enemies of the state.

John Amery is one of three people whose actions, backgrounds and fates Judith Keene explores in Treason on the Airwaves. Each was charged after making broadcasts on Axis shortwave radio from occupied or enemy territories during World War II. Amery, in London, pleaded guilty. A magistrate in Sydney in 1946 found Charles Cousens had a case to answer about his Radio Tokyo broadcasts, but the state did not proceed with the prosecution. Iva Toguri, ‘Tokyo Rose’, who worked with Cousens in Tokyo, was found guilty in 1949 and served seven years of a ten-year sentence in Alderson, West Virginia, before being granted parole.

Each of these stories has been told before, Amery’s most recently in Oscar-winning screenwriter Ronald Harwood’s play An English Tragedy (2008). Keene’s purpose is to draw them together, contrasting the handling of alleged treacheries in one war by three nation-states that fought on the same side. She does not want to be an advocate for the individuals, but to illuminate their related stories ‘by setting the protagonists within the choices that separately were available to them’, and examining ‘how their governments held them accountable for these choices after the war’. The large issue of treason is investigated by reconstructing the little details of individual lives.

Keene is especially interested in ‘historical context and contemporary contingency’. Treason has legal definitions, but ‘behaviour that fell under that legal rubric evoked a whole range of responses’. The fates of the three accused were influenced not just by the details of their activities and personal backgrounds, but by the timing of prosecutions, public moods, the conduct of the cases and deeper racism and sexism.

Amery, captured in Italy by the Allies in April 1945, may have been a victim of the immediate postwar desire for retribution, although there was no doubt about the fact and nature of the broadcasts he made from Berlin, denouncing Jews, Americans and Russians, and urging British people to bring down the government (in which his father was Secretary for India and Burma) that supported them. The following year, in Sydney, the Commonwealth was reluctant to prosecute Cousens and caused outrage when Japanese witnesses were brought to Australia at great expense to testify against him.

Toguri was imprisoned by the occupying Americans, released then re-incarcerated, and finally brought back to San Francisco for trial late in 1948. If timing was all that mattered, the diminished lust for revenge should have helped her cause. But the emerging Cold War that encouraged America to imagine Japan as part of its realigned sphere of influence also preserved space for retribution against a very few of those thought to have undermined the nation’s efforts in the earlier conflict.

Toguri, the young American-born daughter of Japanese immigrants, was one of 50,000 second-generation foreign-born Japanese in Japan before Pearl Harbour. Born on 4 July 1916, she told American investigators in Tokyo she had been a Girl Scout, played the piano and had a crush on Jimmy Stewart. She thought of herself as mainstream, but the FBI found Anglo doubters, including neighbours who were troubled by the row of cypresses the family had planted in their Los Angeles suburb ‘to screen off their backyard’.

In Japan, ostensibly to connect with her real origins before the war, Toguri delighted in an Americanness completely at odds with prevailing social expectations, more Scarlett O’Hara than ‘well-brought up Japanese girl’. Initially a typist at Radio Tokyo, she was drawn into English-language broadcasting by the Australian Cousens, a successful broadcaster with Sydney’s 2GB before the war, who was captured when Singapore fell and brought to Tokyo. He wrote Toguri’s scripts for the popular Zero Hour program and travelled to the United States to testify in her defence.

There are back-stories of people and families, stories of wartime broadcasting and three courtroom dramas here, but there is also a story about the nature and impact of media, speech and law. What did these three alleged traitors say, did anyone make them say it, what did they mean, and did their words make any difference?

Amery’s broadcasts appalled his parents, who listened to them in Euston Square, but Churchill, who knew something about errant sons, was understanding. John had almost no success recruiting British POWs to fight the Russians on the Eastern Front. Cousens insisted every word he wrote and spoke was crafted to subvert the propaganda purpose his masters intended. The Japanese thought American music would make the American sailors in the Pacific homesick; Cousens thought it would remind them what they were fighting for.

It turned out ‘Tokyo Rose’ was not really Iva Toguri, but a mythical amalgam of many female voices. A mixed-race San Francisco jury struggled to pin the words and the intent so many claimed they had heard to the woman sitting before them in the dock, even with the help of prosecution witnesses who late admitted taking bribes for their testimony. Toguri couldn’t imagine anyone thinking she was being anyone but herself. ‘Hullo friends, I mean enemies in the Pacific,’ she would say, reading Cousens’s words.

When the guns fall silent, what is left of words uttered as they raged? What do nations make of the people who spoke them? Keene helps readers understand that the law is an imperfect tool for answering these questions, though answer them we must.

Comments powered by CComment