- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

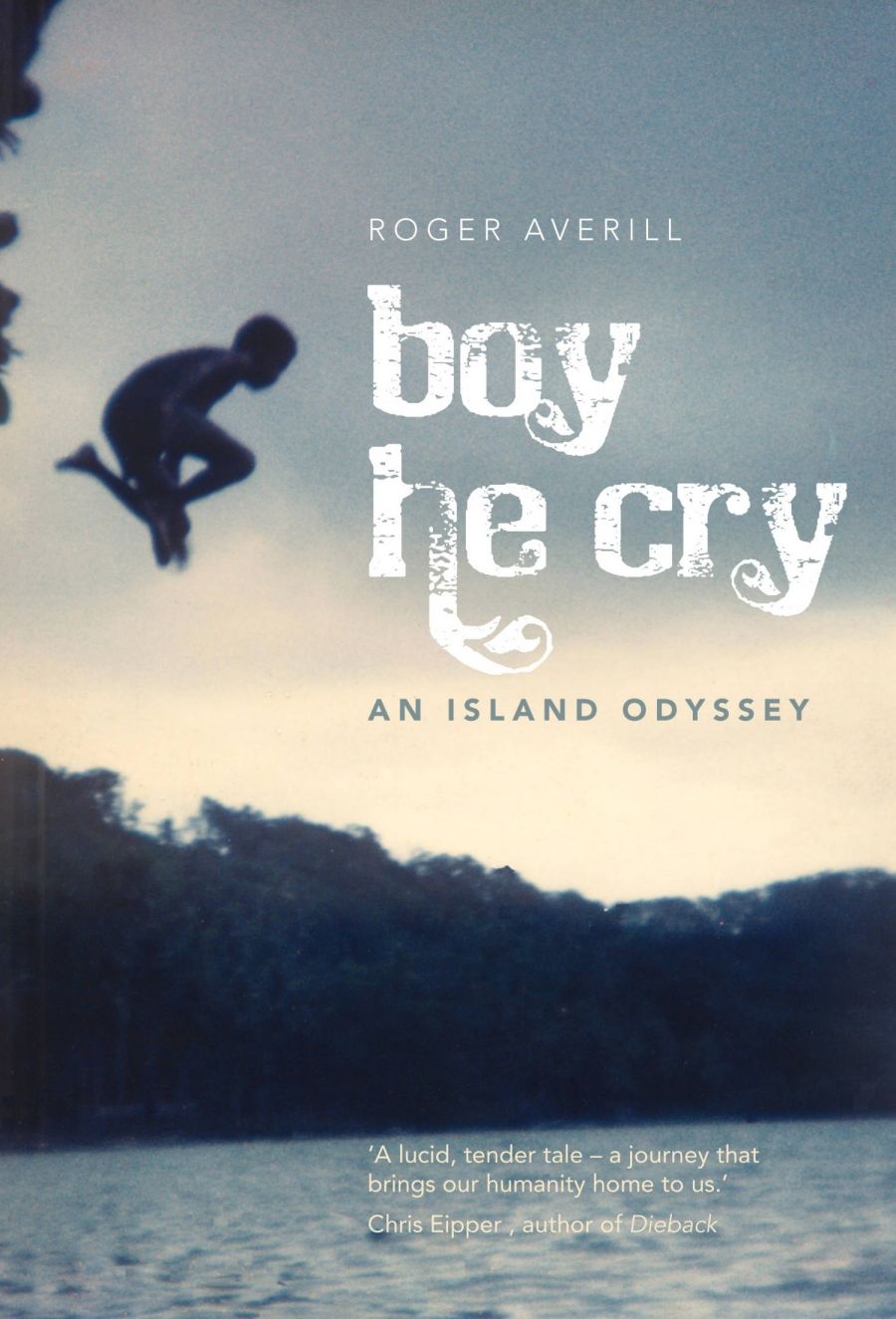

- Custom Article Title: Jane Goodall reviews 'Boy He Cry' by Roger Averill

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tides of conviction

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Boy he Cry’ or ‘Gwama’idou’ is the name of a boat owned by one of the inhabitants on Nuakata, the Melanesian Island that is the setting for Roger Averill’s odyssey. The boat is a canoe, hand-carved and painted yellow, with a bright plastic sail, so there is something incongruous about its poignant caption, which, as Averill learns, refers to a local expression: when a boy is hungry and cries for fish, his father must go out and catch it, so demonstrating his love for the child. In this case, there is an additional melancholic twist because Guli, the owner of the canoe, is separated from his son and unable to hear him cry. Averill’s story is permeated by a doubleness of mood that takes a while to reveal itself.

- Book 1 Title: Boy He Cry

- Book 1 Subtitle: An island odyssey

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $32.95 pb, 310 pp

It is easy to be won over by this generosity of spirit, and by its responsiveness to the extraordinary kindness of the local people. Averill’s writing also fosters trust through its candour and directness. The economy with which he serves up the particulars of a scene serves more effectively than descriptive virtuosity to promote absorption; his account of riding out a storm at sea on a tiny boat is extraordinary and memorable for its focus on the practicalities of survival. On the downside, there is a lack of agility in the language. One secret of that rarely practised art of the plain style is a deft management of sentence structures, but this is not one of Averill’s strengths. His habit of forming sentences on the same syntactical pattern, starting with a subordinate clause, becomes a distracting mannerism.

The question of what kind of writer Averill is looms by implication throughout the narrative. He is the ethnographer’s partner, and is crossing the cultural divide with a perceptual approach that steers clear of the kinds of observations she sets out to make. There comes a point towards the end of their time on the island when, wracked by malaria, Averill seeks help from a traditional sorcerer who administers green potions, mimes the slicing and dicing of his spleen, and massages his head with wood shavings before ceremoniously extracting a shard of glass from his forehead, supposedly the cause of his ferocious headaches. In the aftermath, Averill feels himself suspended between two cultural realities and wryly imagines an advance on Malinowski’s method of participant observation, ‘whereby it is the participant’s loved one who is fully immersed in the culture’.

Yet, in spite of being taken physically and psychologically to the brink, Averill is never fully immersed, and the melancholic undertones of the narrative emerge through a concern with the radical dislodgement of belief systems. During his time on the island, he works on a novel about keeping faith. Following the ordeal of the tempestuous boat trip, Averill reflects on the literal experience of ‘all being in the same boat’ in the face of death. ‘I have never been (nor really understood) the sort of person who goes through life without regularly contemplating its existential realities,’ he says. When the recurring attacks of malaria eventually become life-threatening and force his return to Australia, he is distraught at being wrenched away from a preferred reality. ‘The paradox was that this time in my life when I felt most alive was also the one when I was closest to death.’ The experience of leaving it constitutes some primal form of separation anxiety. Boy he cry.

The space between cultures is hazardous terrain for any writer with a post-colonial awareness of how words expose attitudes and how attitudes can betray moral failures that amount to a contemporary secular equivalent of original sin. As a Dimdim (white foreigner), Averill’s odyssey is ‘an ongoing lesson in the contradictions of the human heart’, and he is vigilant about the behaviour of other visiting Dimdims. Not that he is given to sermonising, or to rhetorical positioning. Rather, offences against the bedrock principle of intercultural respect are taken personally, and rankle through the pages long after the offenders have left.

More nuanced principles of culturecrossing are the ethnologist’s preserve, outside the terms of his own engagement with the situation, which evidently have something to do with the Methodist evangelism that dominated his childhood, and whose tenets he needs to renegotiate. Although it has left him an agnostic, with a dislike for crusading certainties, he retains an instinctual determination to keep faith with certain aspects of it. There is another crying boy on Nuakata, who has been detected in an act of petty theft through the magical divinations of a wise woman in the community. Experiences of transgression and remorse, perhaps, have an existential hold on us that crosses the divide between belief systems. The same may be true of faith and grace, the reality of which, Averill says, he began to understand through the generosity extended towards him by the islanders.

Such associations are only made occasionally, and without polemical embellishment, but also without recognition that in the cultural milieu of metropolitan life to which he is now returned, and to which most of his readers will belong, they are profoundly unfashionable. Intellectual fashions don’t make their presence felt anywhere in this book. It communicates virtually no consciousness of cultural temporality. When I got to the end, I found myself wondering where or how I had failed to pick up on its chronological bearings. There are no references to world events, political contexts, or contemporary reading matter. Did this island odyssey occur two years ago or ten? More like fifteen, I discovered from a Radio National interview transcript.

Timelessness is an underlying theme of the odyssey. Through the ‘hours and long days of ordinariness’, an abundance of time is taken for granted, and Averill warns the islanders against selling it in exchange for the Dimdim luxuries they have inevitably started to covet. All they need, he advises, is better medicine and some equipment for the school. He steers clear of idealism in his account of how they live – indeed, the cruder and more dangerous aspects of it are vividly portrayed – and if there is a tradition to which his narrative belongs, it is closer to that of the stoical Western misfit who sets out into the world prompted by some internal compulsion to find the vital bearings lost in a life lived amid the comforts of home. I am reminded of Annie Dillard’s caution about not confusing leaving with living (An American Childhood, 1987), a maxim that has some relevance here, given the marked absence of any imaginative engagement with the cultural world left behind, and presumably now rejoined. Maybe Averill should write a sequel, about living in Melbourne.

That is a bit of a random suggestion, of course, but I don’t mean to be facetious. In metropolitan cultures, the tides of conviction are turning in unanticipated ways. The developed world is due for an existential crisis, Ban Ki Moon has been saying. Keeping faith with the tenets of the free market world is becoming more and more of a strain. I was engaged by this book – at times deeply so – but left with a sense that there is something evasive about it. Why the extended lapse of time between the experiences it recounts and the time of publication? More to the point, what might the time lapse add to the perspective? There is more to be said, of that I’m convinced.

Comments powered by CComment