- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Ann-Marie Priest reviews 'Awakening' by Eileen Chanin and Steven Miller

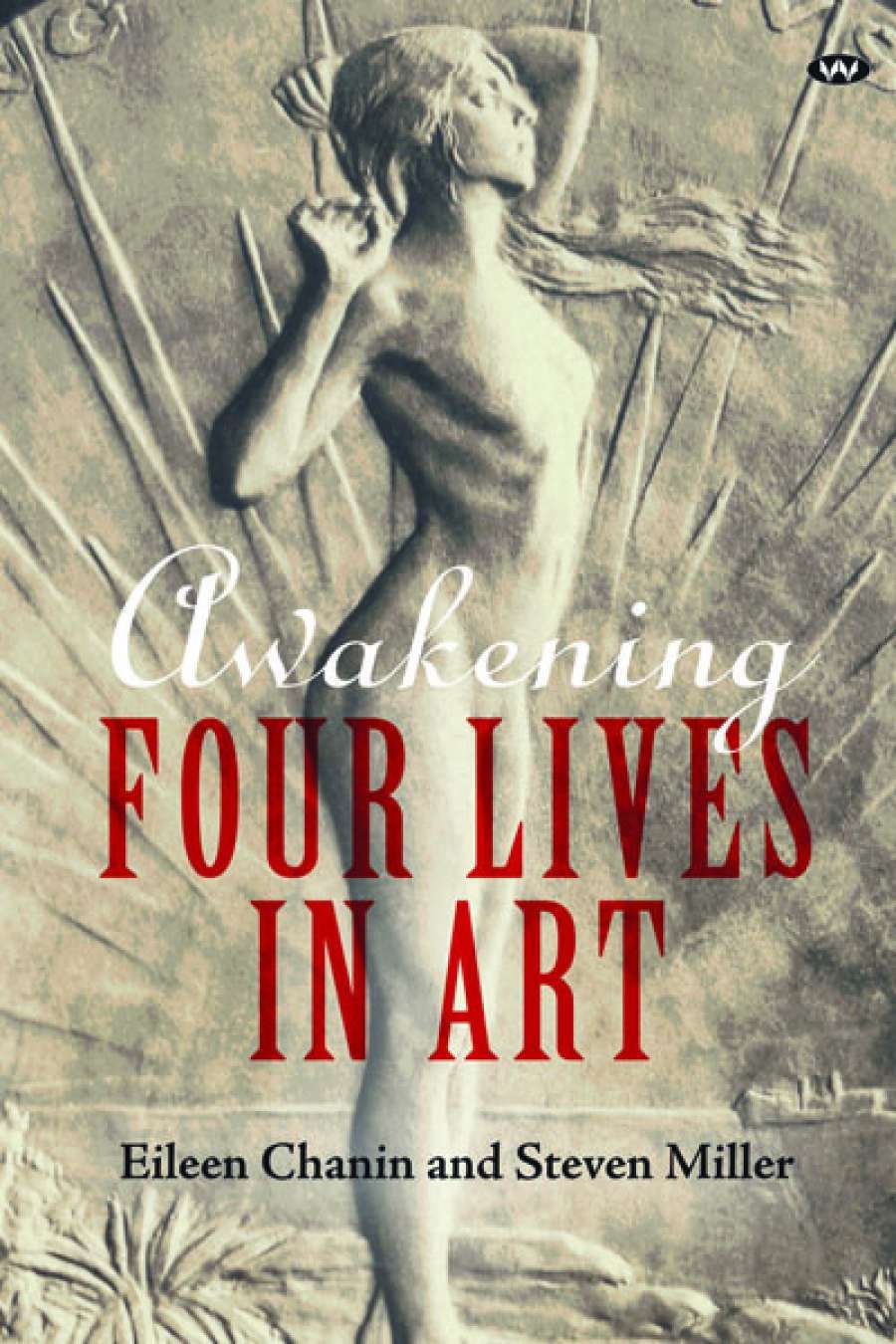

- Book 1 Title: Awakening

- Book 1 Subtitle: Four Lives in Art

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $39.95 pb, 240 pp, 9781743053652

It is clear from the structure of the book – four brief biographies presented in parallel, with no attempt at a unifying narrative – that the authors’ purpose is not argument or analysis. Drusilla Modjeska showed in Stravinsky’s Lunch (1999) that the lives of long-neglected women artists can seduce and enchant, resonating far beyond their own time and social context. In the absence of Modjeska’s superb storytelling skills, however, Chanin and Miller need to work much harder to capture the reader’s interest and draw out the significance of the lives they record. In this, their conventional approach to biography does not serve them well. The level of detail they provide about each woman’s parents, in particular, is unnecessary, and their accounts of their subjects’ upbringings often get bogged in generic information about the historical context. When the stories do finally get underway, they are cut off in mid-stride at the seemingly arbitrary end point of 1939.

The superfluous detail in some areas is matched by a lack of information in others. I was curious about the partnership between Dora and Elena (‘a celebrated beauty’ who may have worked as an artist’s model), given that lesbian relationships at the time tended to be either invisible or pathologised. But Chanin and Miller tell us only that they were an ‘attractive couple’. Did they live openly as lovers? Was there, perhaps, a culture of homosexuality among expatriates in Rome, as with Natalie Barney and her circle in Paris? What was the significance for Ohlfsen as an artist of having a female partner? Did it enable her to focus more completely on her art? Chanin and Miller do not even begin to canvas such matters.

Dora Ohlfsen, Ceres, 1910 (Collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney)

Dora Ohlfsen, Ceres, 1910 (Collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney)

‘One of the few Australian-born female sculptors of the early twentieth century was a Ballarat girl, Dora Ohlfsen, who went to Berlin in 1892, at the age of twenty-three’

Similarly, I had many unanswered questions about Mary Allen’s bohemian life in Greenwich Village. As an artist, she was apparently known in America as Cecil Allen, yet Chanin and Miller do not comment on her use – which is not without precedent, though more common among writers – of a male pseudonym. Like Ohlfsen, Allen never married, but we are told almost nothing about her private life. Such details are always important in considering the lives of women artists – as the well-established literature on the subject reveals. Historically, marriage and motherhood have taken an enormous toll on women’s careers, and only by finding alternatives to conventional familial models have some female artists been able to work at all. It is no coincidence, I am sure, that only two of the four women in this book were married, and only one – Clarice Zander – had a child. Significantly, Zander, who raised her daughter alone, shelved her artistic career early and definitively, pursuing instead more financially stable work as a manager and publicist.

Louise Dyer with sculpture c.1920 (courtesy of the Bibliothèque National de Paris)

Louise Dyer with sculpture c.1920 (courtesy of the Bibliothèque National de Paris)

Chanin and Miller are hindered in their task by an apparent paucity of personal sources – letters, diaries, memoir. When they do draw on such sources (Joan Lindsay’s lively recollections of Mary Allen, for instance) the women flame briefly into life. The striking photographs of each woman also tell a vivid story, with Zander, for example, appearing at twenty-one in an elaborate Victorian neck-to-knee bathing costume, complete with parasol, and at forty-one in a strappy modern swimsuitthat would not look out of place on a beach today. But even with the book’s engaging illustrations, Chanin and Miller largely decline to draw the significance; indeed, references in the text to the coloured plates are often puzzlingly random.

In the brief epilogue, the authors elect not to draw any conclusions, but instead provide hurried summaries of the untold portions of each life – which did save me some time on Google. It also served to emphasise, however, the book’s larger failure to focus on what makes each of these ‘remarkable’ lives significant and to evoke their unique personal texture.

Comments powered by CComment