- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Francesca Sasnaitis reviews 'Crow's Breath' by John Kinsella

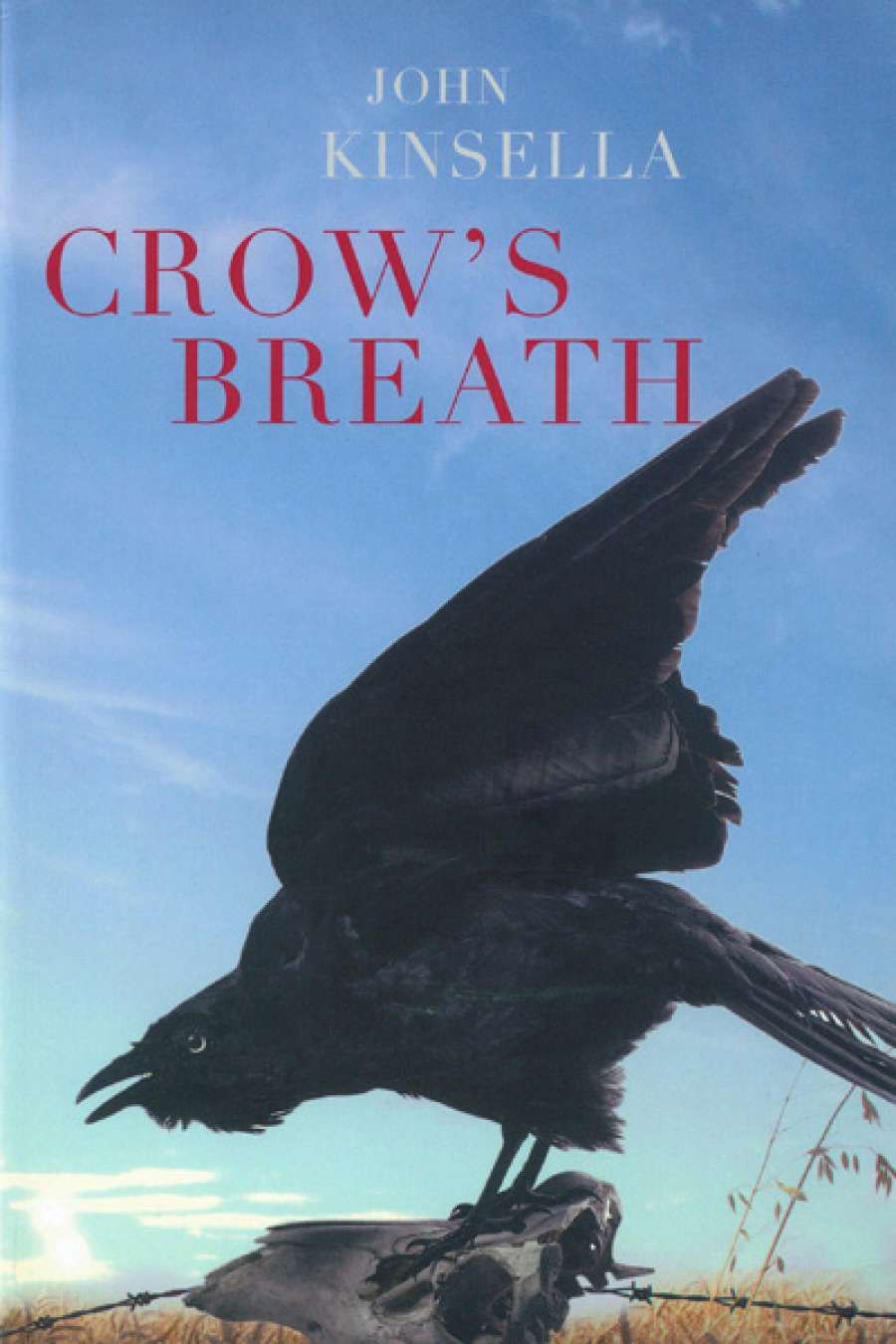

- Book 1 Title: Crow's Breath

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $25.95 pb, 208 pp, 9781921924811

The title story features a creepy child practising do-it-yourself taxidermy, a grandfather wallowing in discontent, and an unnaturally cheerful, blowzy mother in an Australian version of Southern Gothic. As if crushed by the narrators’ broad Aussie accents, the prose seldom rises to the eloquence of the following passage:

Dusk is a crushing time for a dying town. If dawn surprises and mocks with hopelessness, the suggestion that light might lift it all, then dusk is worn out and can’t be bothered taunting. Crow’s breath, the maintenance workers called it, enough to singe the [wheat]bin’s whitewash. And when that goes, this town will sink under the murk.

The family, which sits on the verandah staring at the silo with rapacious tenacity, are the ‘whitewash’ (or white trash), the offensive Anglo-European veneer laid over country that does not truly belong to them.

In ‘Monitor’, the blight of whiteness plays out in ‘skin’: the scaly skin of goannas; the threat of melanomas; the ‘overly white skin’ of the station owner and the black skin of her station hand; the significance of ‘skin’ to Aboriginal kinship and to other systems of loyalty; the canker of unchecked property development. It is about race, class, and greed. Mary’s flirtation with Black Dan causes consternation among the founding families of the district, for whom ‘such white skin is to be treasured, to be filed away for breeding and archival purposes, a legacy of origins, an insurance against country’s merciless assimilations’. Years later, a developer’s son stands before Mary like an Old Testament prophet with a box of matches, and declares, ‘This town is a town of hate and needs purging.’ And she, dressed in the white robes of the Blessed Virgin, answers his despair with a confession and a conflagration.

‘This is the wheat belt region of Western Australia to which John Kinsella appears to lay claim as surely as Tim Winton claims the coast’

The black–white dichotomy and quasi-mystical tropes play out in stories of class-comeuppance on the wheat belt, and when the location shifts abruptly overseas. On Réunion, a disturbed young woman, who wears a designer evening frock to feed the island’s feral dogs, appears in the role of Holy Fool to expose the hypocrisies of the insular middle classes (‘Feeding the Dogs’). Off the coast of West Cork, a piratical local and a seal called Nippy bring a pair of innocuous architects to account (‘Binoculars’). During Halloween in an Irish village, offended spirits ‘reach through the membrane’ between the worlds and drive a reclusive Australian mad (‘The Thin Veil’). And in the stories that shift between the wheat belt and Ohio, one protagonist is ‘snow-blind, defaced by the storm of whiteness that had swept the world’ (‘Golden Gloves’), and another has a head ‘full of static, the snow of American cable television’ (‘Dirty Snow’).

John Kinsella at Gathercole (photograph by Tracy Ryan)

John Kinsella at Gathercole (photograph by Tracy Ryan)

A breath of the sinister permeates many of the stories, including those not overtly speculative. In ‘On Display’, a part-time father takes his son to a classic steam engine exhibition, where he meets a woman who seems to know all about him. The man has been forced to move around to find work, and, like the disused trains, has lost his ‘place in the scheme of things’. The man teeters on the edge of remembering. The woman speaks with the voice of an oracle, or a ghost:

When those steam trains were running they poured out the pollution.

No heart to leave, no heart to return to.

And now just on display.

Yes, that’s the way of it.

The line breaks of this conversation read like poetry. Other sections of dialogue are more pedestrian, trite phrases following each other in what is, perhaps, an apt imitation of commonplace exchange.

Desperate and often unsympathetic characters populate these stories: pushy mothers and broken fathers; pampered, neglected, or discomfiting children; sexual predators, psychotics, and ghouls. No stalwart farmers in the Russell Drysdale mould here – Kinsella’s Aussie battlers are embittered by the hardships they have endured. Small-mindedness and limited expectations have made them nasty. If they experience any sense of guilt, or a momentary glimmer of self-disgust, it is short-lived. To them, and to us, Kinsella sends a clear message: we will reap the consequences of our blatant disregard for each other and for the planet. Beware! he says, ‘the snow has gotten into the soil and the temperature is rising’.

Comments powered by CComment