- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Rachel Buchanan reviews 'Silent Shock' by Michael Magazanik

- Book 1 Title: Silent Shock

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 368 pp, 9781922182098

In 1961, Melbourne woman Wendy Rowe had a toddler and a four-month-old when she fell pregnant again. She was worried and unhappy, unsure of how she would cope with yet another baby. The family GP prescribed a new medication to ‘calm her’ and to ease her acute morning sickness.

Wendy took thalidomide for five weeks. As Magazanik writes: ‘Scientists would later learn that a single tablet was sufficient to kill or severely malform an unborn child.’

Wendy’s baby, Lyn, was born in Box Hill Hospital. The birth story, narrated by the now elderly GP who delivered Lyn, is not one I will forget. There were no ultrasounds then. No one knew anything was wrong.

‘The baby started to come out. Head first, everything OK. But then I saw that there were no arms. And then no legs. The little girl had only a torso and a head,’ Ron Dickinson told Magazanik.

Ten months later, Lyn suffered brain damage after catching a fever and falling into a coma, an event common in thalidomide babies. Lyn’s parents, Wendy and Ian, had cared for her ever since without any compensation. They had accepted a doctor’s assessment that a virus was to blame for the injuries.

The Rowes only agreed to join Melbourne lawyer Peter Gordon’s claim because they were worried about how they could keep looking after Lyn. Wendy, aged seventy-four, had started to do weights so she would still be able to lift her daughter.

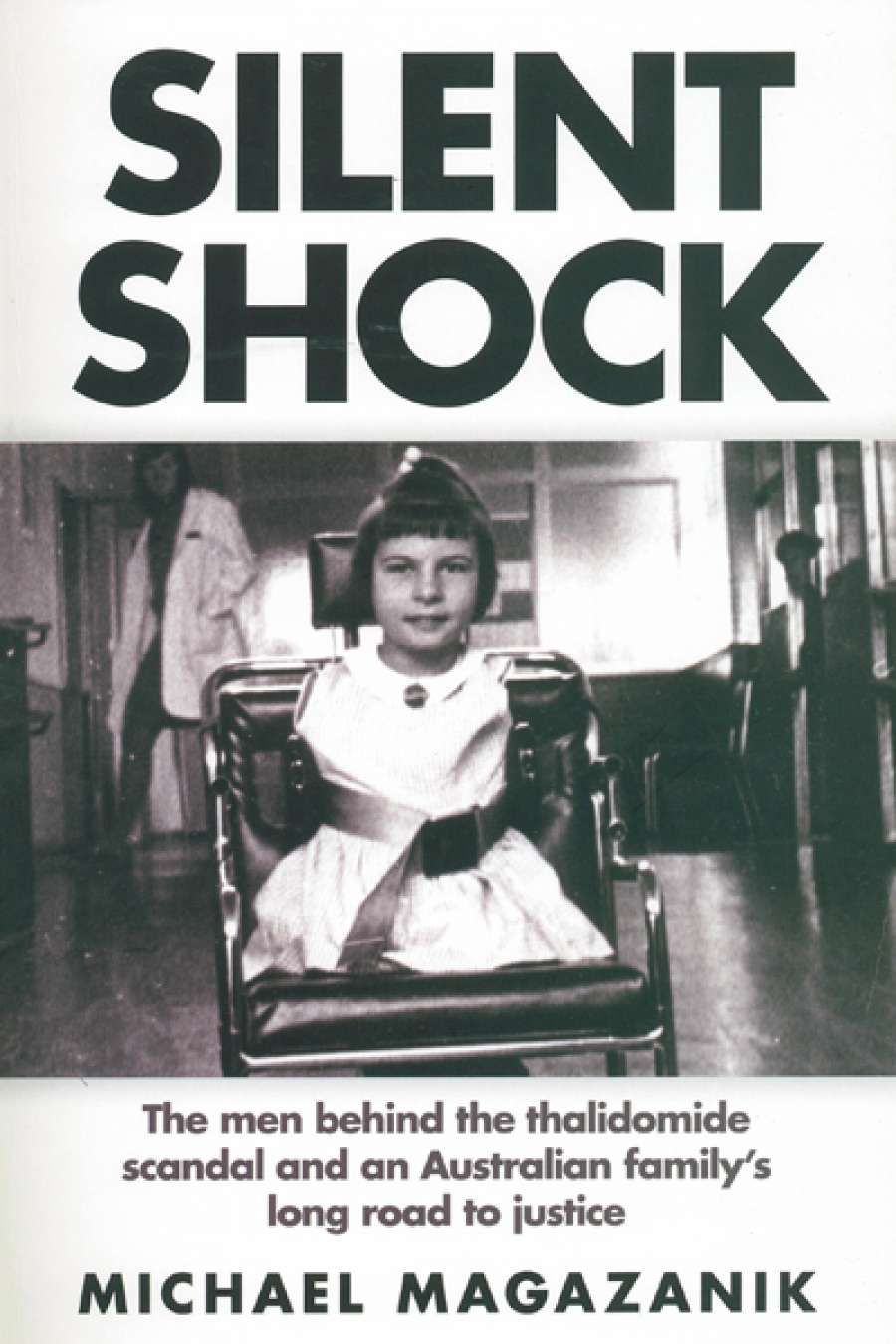

The Rowe family in the 1960s

The Rowe family in the 1960s

Their story was so compelling that Lyn became the lead plaintiff. It was Magazanik’s job to gather detailed legal statements from the Rowes. He met them in 2011. During the interviews, he was often bug-eyed with sleep deprivation; his first child was only a few months old:

I asked Wendy in passing when Lyn had first slept through the night. She laughed. ‘What do you mean? She’s never slept through the night! I get up two or three times a night to move her or help her use a bedpan. I’ve been doing it since 1962.’

With this naïve exchange, Magazanik demonstrates the heroic love and endurance of this extraordinary woman, but the snatch of dialogue also hints at other possibilities for this book. It could have been one that truly dwelt on the ‘private history’ of this ordinary Australian family.

‘Thalidomide was sold from 1957 until late 1961. It killed or disabled between ten thousand and fifteen thousand babies around the world’

Silent Shock includes a small section of colour images. The photos from the Rowe family album are tender but wrenching. What did it cost this family to maintain the rituals of suburban life – trips to the beach, baby snaps, the family portrait in front of the brick veneer house – with a child who was so disabled? We never really find out.

We get glimpses of father Ian’s struggle with anxiety, the regret Wendy feels over the lack of time she had for her three other daughters, the poverty they have endured.

Silent Shock covers so much ground that the Rowe story can disappear from view and the narrative drive is lost. That said, Magazanik does an excellent job of summarising the history of the drug and the dysfunctional culture of the company that made it. Several Grünenthal executives were convicted Nazi war criminals. The company’s attitude remains bizarre. The book’s title refers to chief executive Harald Stock’s 2012 apology to victims. ‘We ask that you regard our long silence as a sign of the silent shock that your fate has caused us,’ Stock said.

‘Their story was so compelling that Lyn became the lead plaintiff’

Magazanik is writing against this silence. A strong theme is the cowardice of individuals who knew that thalidomide was injuring babies but did not speak out. The legal team uncovered a shocking example of this in the Distillers’ Sydney office. For six months in 1961, executives failed to act on reports of deformities caused by thalidomide. Instead, they fretted about ‘the implications for the business’ if the reports were true. Had they acted, Wendy Rowe would never have taken thalidomide.

In 2012, Lyn Rowe reached a multi-million-dollar confidential settlement with Distillers (now owned by Diageo) and in 2013, Diageo agreed to an $89 million package for the other survivors. Grünenthal wriggled free.

The Herald Sun splash on this amazing win is reproduced in the book. The accompanying photograph shows two men in suits – Magazanik and Gordon – behind two women in more flamboyant outfits. Monica McGhie wears a safari kaftan, while Lyn Rowe’s black skirt has bright blue flowers growing from the hem. The outfits drape over the seats of their motorised scooters.

McGhie and Gordon are chortling, but Rowe stares out with a look of absolute accusation and pain. After her payout, Lyn bought herself two new denim jackets. Her parents bought a small coffee machine. ‘It seemed like such a massive indulgence,’ Ian said.

Comments powered by CComment