- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: Billy Griffiths reviews 'Unholy Fury' by James Curran

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

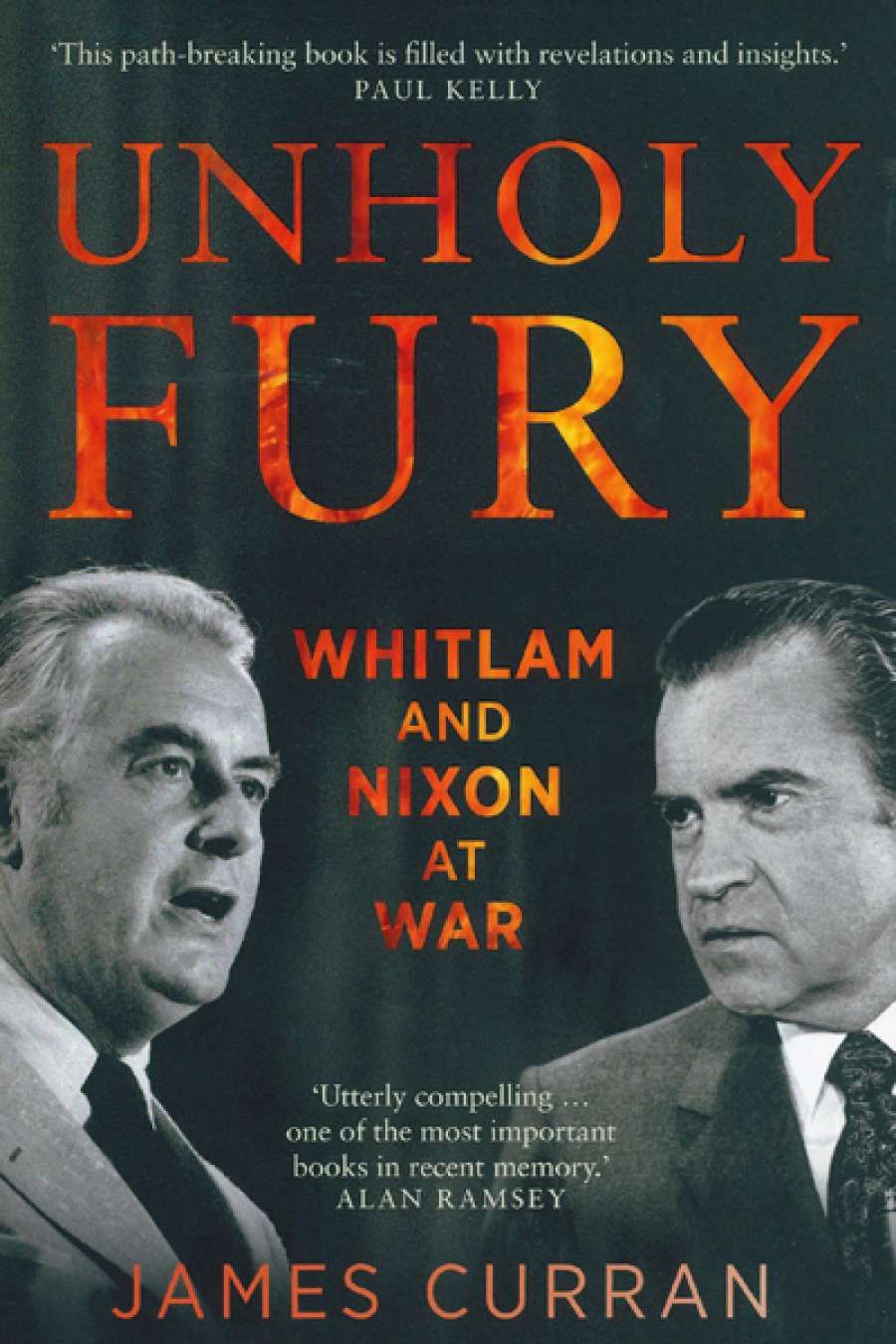

- Book 1 Title: Unholy Fury

- Book 1 Subtitle: Whitlam and Nixon at War

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $39.99 pb, 378 pp, 9780522868203

Thus began the unprecedented feud between these two powerful and enigmatic leaders. It was fuelled by some of Whitlam’s senior ministers weighing in on the so-called ‘Christmas bombings’ by publicly accusing the White House of being run by ‘maniacs’ and ‘thugs’. Behind closed doors, the White House vented about ‘that god damn Prime Minister’. Whitlam was derided as ‘a bastard’ and as ‘one of the peaceniks … putting the Australians on a very, very dangerous path’. As a sign of the seriousness of the situation, Nixon appointed Marshall Green, one of America’s most skilful Asia experts and policy makers, as his new ambassador to Australia. His parting instructions on Whitlam were clear: ‘Marshall, I can’t stand that [****].’

Curran savours every new piece of evidence in this unfolding saga and brings a mass of diplomatic documents to life with his fierce wit and lively turn of phrase. It is indeed ‘sensational’ how much the alliance deteriorated in the early 1970s. Curran reveals that Nixon ‘gave more than a passing thought to abandoning ANZUS altogether’, and he unpacks conversations in which senior US officials ‘spoke of Whitlam, and Australian politics more generally, in the way puppeteers would talk of their marionettes’. In the final chapter, he tackles, and ultimately rejects, the suggestion of CIA influence in Whitlam’s dismissal in November 1975. Though he concedes, along with Paul Kelly, that the timing of events ‘provided the necessary material for a conspiracy theory’.

Whitlam and Nixon, 30 July, 1973 (National Archives of Australia)

Whitlam and Nixon, 30 July, 1973 (National Archives of Australia)

But Unholy Fury is more than simply a portrait of Nixon and Whitlam and their clash of egos and ambitions: it is an interrogation of the alliance that bound them together. Curran picks apart the tenuous emotional bonds that sustained the alliance throughout its first two decades, offering rich vignettes of the successive Liberal prime ministers who vied to keep the ANZUS treaty relevant. Their obsession with the cosmetics of the alliance, particularly meetings with the US president and planned demonstrations of spontaneous friendship, is both comical and revealing of the relationship’s soft underbelly. As Curran reminds us, neither Harold Holt’s famous declaration of going the ‘all the way with LBJ’, nor John Gorton’s promise that ‘we will go Waltzing Matilda with you’, resulted in closer consultation and coordination of policy between the two countries: both prime ministers were routinely left uninformed of American policy initiatives, as was William McMahon over Whitlam and Nixon’s respective China coups. It was only under Whitlam that the alliance achieved ‘a new maturity’.

‘For all its enduring importance,’ Whitlam reflected in January 1973, ‘adherence to ANZUS does not constitute a foreign policy.’ His ‘stiff message’ to Nixon over the Christmas bombings was a natural part of the ‘more mature and less adulatory’ approach to world affairs he had patiently constructed in opposition. The irony underlying the book is that both he and Nixon were attempting to do similar things. While they clashed over the end of the Vietnam War and the shape of a new Asia, they shared common ground when it came to China and détente with the Soviet Union, and they were both eager to take their respective nations in bold new foreign policy directions. But neither leader was able to ‘adequately understand the dilemmas the other faced’. Whitlam refused to temper the language or the speed with which he reshaped the alliance, despite dealing with a White House bleeding from war weariness and political scandal. And Australia’s new direction would have been the furthest thing from Nixon’s mind as the Watergate revelations took a chokehold on his presidency.

By the time Whitlam was dismissed from office, the Australia–America alliance was not as close as it had once been, but in many ways it was healthier. ‘This is not,’ Curran stresses, ‘to elevate Whitlam as a Labor Hero, poking President Nixon in the eye and beating the drum of Australian nationalism all the way to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.’ But under Whitlam, a beleaguered White House was forced ‘to accept that it could not bend Australia’s new arc to its will’. The days of sycophancy and me-tooism were over (for the time being), and the alliance was stronger for it.

Curran ‘makes no apology’ for examining the power centres that shape world affairs, and he homes in on the actions of the ‘key players’ that drive the story. But his tendency to view international events through the prism of American foreign policy occasionally downplays the agency of other factors. The assertion, for example, that ‘it was the Americans who … gifted Whitlam his China coup’ understates the changing international climate of the early 1970s and China’s bold new phase of outward-looking diplomacy. This, however, is a minor quibble in what is a sophisticated political thriller.

Curran leaves the question of Australia’s contemporary love affair with America to be answered by ‘future historians’. As for the dramatic events recorded in Unholy Fury, he records one final slight the Americans accorded the Australian prime minister: ‘Neither Nixon nor Kissinger devoted a single line to Whitlam in their respective, voluminous memoirs.’

Comments powered by CComment