- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Frank Bongiorno reviews 'Trendyville' by Renate Howe, David Nichols, and Graeme Davison

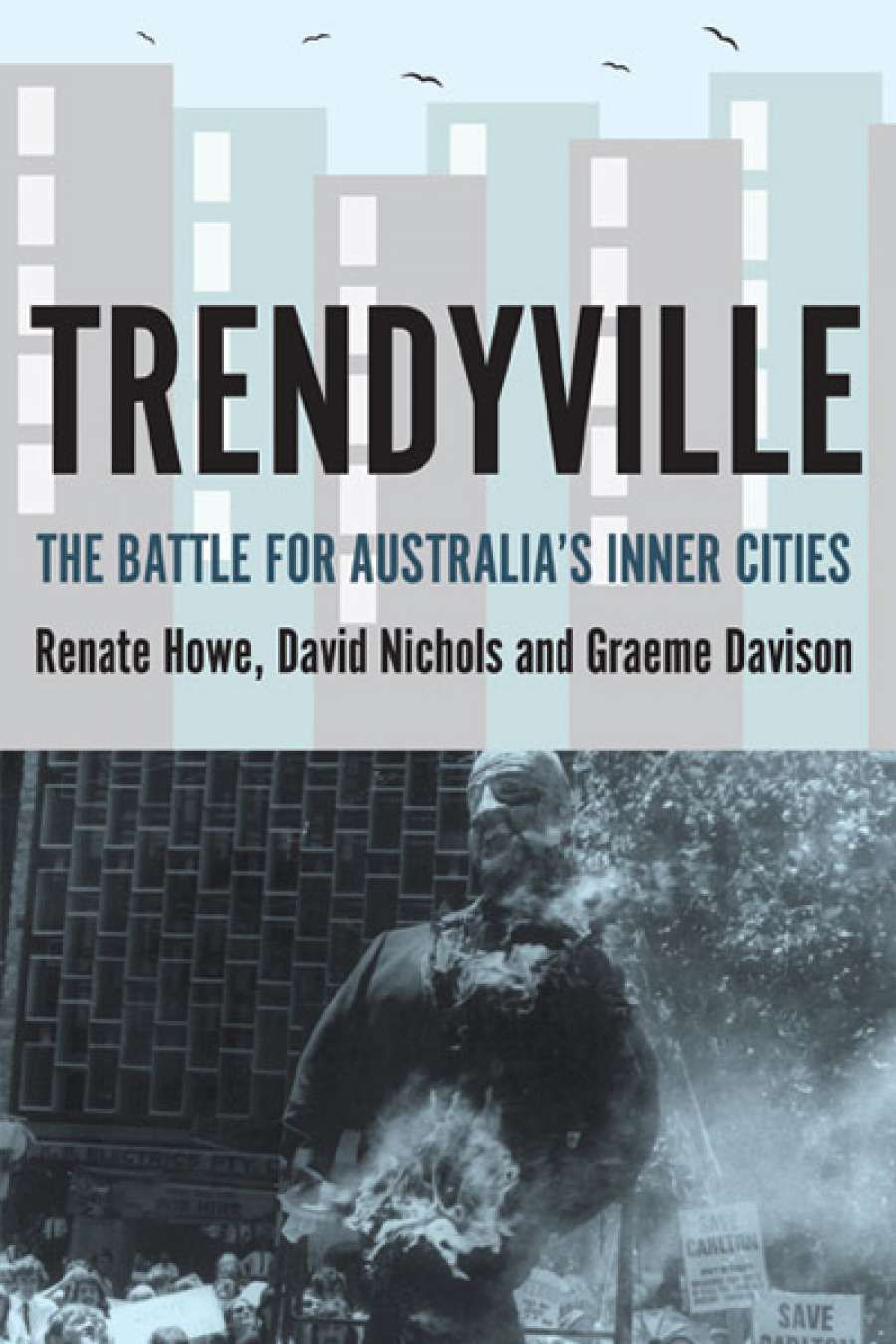

- Book 1 Title: Trendyville

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Battle for Australia's inner cities

- Book 1 Biblio: Monash University Publishing, $34.95 pb, 218 pp, 9781921867422

Trendyville is a welcome study of the battles fought over the future of the inner city during the 1960s and 1970s – those suburbs just a little closer to the city than my own. It is mostly concerned with Melbourne’s inner suburbs, and especially Carlton. Renate Howe, David Nichols, and Graeme Davison only briefly discuss Sydney, and they do not seek to cover in any detail the same territory as Verity and Meredith Burgmann on Sydney’s green bans, or the late Tony Harris in his study of inner-Sydney politics. But there is enough comparative discussion in Trendyville to remind us that the struggle for the inner city, while having many common features across the nation (and, moreover, beyond its borders), also took on a complexion deeply influenced by the local scene.

It seems unlikely that anyone in Melbourne, Adelaide, or Perth ever feared that they were placing their lives in danger when they opposed the will of the state or of capital. But in Sydney Juanita Nielsen was probably murdered for her activism while Peter Baldwin received a vicious beating for his. This book is mainly concerned with Melbourne’s traditions of statist social engineering – epitomised by the ‘knock ’em down, put ’em up’ Housing Commission – and the city’s similarly distinctive strain of earnest social reformism, so apparent in the activities of the resident organisations that opposed the commission’s slum clearance and building schemes.

Trendyville’s argument is that the activities of these groups did not amount to nimbyism. Members of resident action groups were to some extent motivated by self-interest, but most had a genuine and idealistic belief in the need for a new form of more democratic and consultative city politics, a commitment to the inner-city life, and a desire to improve the well-being of everyone who called it home. Yet while claiming to speak for the community, they had limited success in connecting with either older working-class residents or migrants. The newcomers often encountered the migrants on their way out, as the latter took advantage of the opportunities on offer to sell up and move away, possibly leaving behind a front yard vegetable garden to be enjoyed by an incoming ‘trendy’.

Rally against the East West Link in Brunswick, supported by Moreland City Council, March 2014

Rally against the East West Link in Brunswick, supported by Moreland City Council, March 2014

The inner suburbs found their activists mainly among the middle class, the affluent, or the upwardly mobile. In a few places, such as Parkville in Melbourne and North Adelaide, theirs was essentially an upper-class or ‘patrician’ activism, a conservative effort to protect the character of an enclave that was already posh. But many newcomers to the inner city had been raised in working-class homes or country towns, and there is a sense in which they were trying to recreate the feeling of living in a ‘village’ they had experienced while growing up. Women were prominent in most organisations, some being elected to local councils and parliament. Young mothers were among the busiest workers for the cause.

‘It seems unlikely that anyone in Melbourne, Adelaide, or Perth ever feared that they were placing their lives in danger when they opposed the will of the state or of capital’

Inner-city activism was both locally and globally inspired. Key American and British texts on modern cities were well thumbed, and leading activists had often seen something of the world beyond Australia. The Methodist minister Brian Howe and his academic wife, Renate – one of the book’s authors – gathered some of their ideas about cities while living in Chicago. Academics and professionals – especially in fields such as architecture, geography, planning, sociology, and history – often had expertise that proved to be a major asset in dealing with the authorities. In Victoria at least, the government was increasingly willing to deal with them. The retirement of Henry Bolte and his replacement by the progressive Rupert Hamer saw a winding-back of madcap plans for more freeways and more high-rise flats.

The way of life available in the inner cities today in many ways reflects the vision of the resident activists of the 1960s and 1970s. But rising property prices since then have ensured that, outside the surviving high-rise blocks, only the very wealthy can make a home there, while governments have wound back more democratic decision-making processes. Nonetheless, the recent struggle over Melbourne’s East West Link has shown that the traditions of such activism have survived to fight another day. Trendyville provides a vivid and well-researched account of how the inner city, which has done so much to persuade ourselves and others that we are truly cosmopolitan, is a product of personal political struggle, as well as of more impersonal economic forces such as globalisation and neo-liberalism.

Comments powered by CComment