- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: John Thompson reviews 'Lost Relations' by Graeme Davison

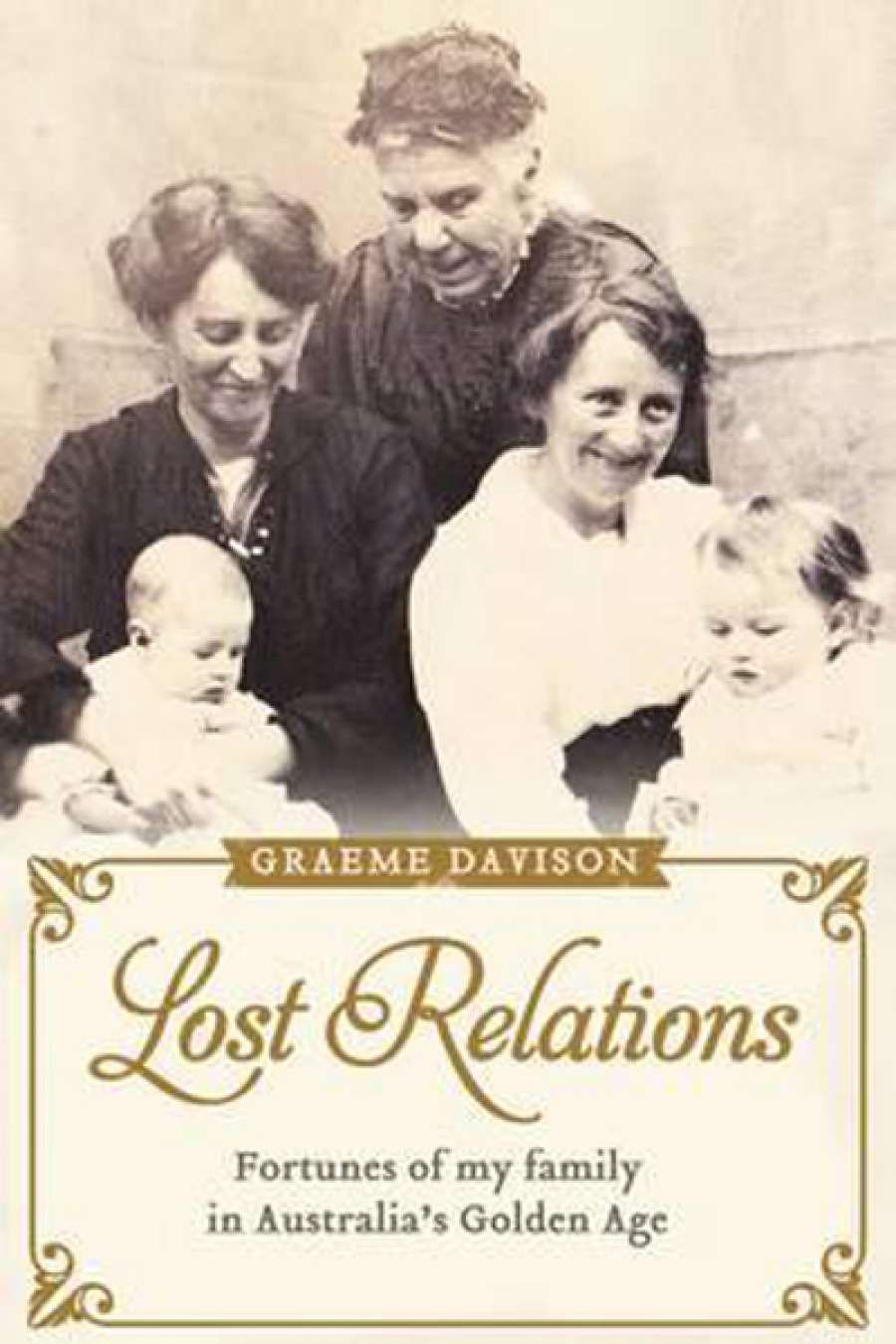

- Book 1 Title: Lost Relations

- Book 1 Subtitle: Fortunes of My Family in Australia's Golden Age

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 288 pp, 9781743319468

More accessibly, the communal past might be called the Australian story. Australia has been profoundly shaped by the experience of successive waves of emigration and of settlement from the eighteenth century to the present day. Davison observes that we are a nation steeped in stories of our immigrant forebears: ‘In every migrant’s story there is a moment of arrival, when the newcomer steps ashore, the emigrant becomes an immigrant and memories of the old country give way to the prospects of the new.’ However difficult the circumstances that led to the sometimes perilous journeys to a remote and distant Australia, a powerful motivating force running through our settler history has been optimism – it has made the country. In the telling of his family story, Davison reminds us of the historian W.K. Hancock’s famous observation that ‘men do not emigrate in despair, but in hope’. Certainly this was the experience of Davison’s Hewett forebears arriving in Melbourne in the middle of the nineteenth century and it was the experience of those who came later whether under sail or steam, by Qantas plane or a leaking boat. On his recent election as the new leader of the Australian Greens, Senator Richard Di Natale reflected on the circumstances of his family’s arrival in Australia after leaving their southern Italian village in the late 1950s: ‘They did not speak any English but they sailed off into the unknown armed with something more important – the hope for a better life … Their story is a universal one. It is on their shoulders, and those of millions of families just like theirs, that this nation has been built.’

‘as an academic historian, Davison avoided family history, perhaps unconsciously minimising or denying the influence of inheritance and kin on his own life’

In Davison’s skilled hands, the mundane particulars of one ordinary family story are compellingly and movingly told. The intimate story of one Australian family becomes also the distillation of some of the major themes of Australian history over more than 150 years, the span that is the passage of time from Jane Hewett’s arrival until Graeme Davison’s own later life at the time of writing. Davison’s fellow historian and distinguished colleague Janet McCalman praises Lost Relations as a quiet masterpiece, a meditation on one Australian family – Davison’s direct ancestral line and several collateral lines – that is also a meditation on country and on the craft of historical enquiry and writing. No mere puff, this is the magisterial endorsement of one fine historian for the work of another. The praise is not gratuitous but richly and emphatically deserved.

‘The intimate story of one Australian family becomes also the distillation of some of the major themes of Australian history over more than 150 years’

The Australian part of this family story begins with the arrival of nine Hewetts displaced by social and economic change from their long and seemingly immutable tenancy of rural acres in picture-postcard Hampshire. And at once a master historian can be seen in play as Davison evokes the personal lives and circumstances of individual family members (as far as these can be determined or inferred where documentation is sparse) while contextualising those lives against the backdrop of the wider social, economic, and political circumstances of the times. He takes the family story down through two generations of his forebears, examining the small details of quiet lives and the workaday occupations of miners, millers, storekeepers, free selectors, railwaymen, homemakers, and printers who each contributed their portion to the diverse fabric of the place we call Australia.

On Davison’s ostensibly small canvas of family history, many much larger subjects and themes are present. Personal lives become the exemplars of diverse but interconnected themes including shipboard life and its placement within the larger story of emigration history, the lives of women, goldfields history, the terrible scourge and pain of infant mortality, the uncertainties and chances of rural settlement, urban and suburban history, the possibilities of social betterment, sectarianism, and the history of Methodism in Australia, the faith in which Davison himself was reared. In the old teaching of Australian history, some of these subjects could seem remote, impersonal, even boring. Here they are enlivened and made vivid, the old generic topics of the syllabus relevant to the understanding we have of ourselves not just as a Hewett, a Davison or whomever, but as members of the wider Australian family.

Davison draws other lessons from his excursion into family history. Pride, of course, but understood more broadly family history should also foster a measure of family humility. In Davison’s generous and compassionate reading, it should embrace the black sheep as well as the white, the wanderers and the stumblers as well as those who march confidently forward to a glorious destination. This is a rich and wise book; it deserves to be widely read and praised.

Comments powered by CComment