- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

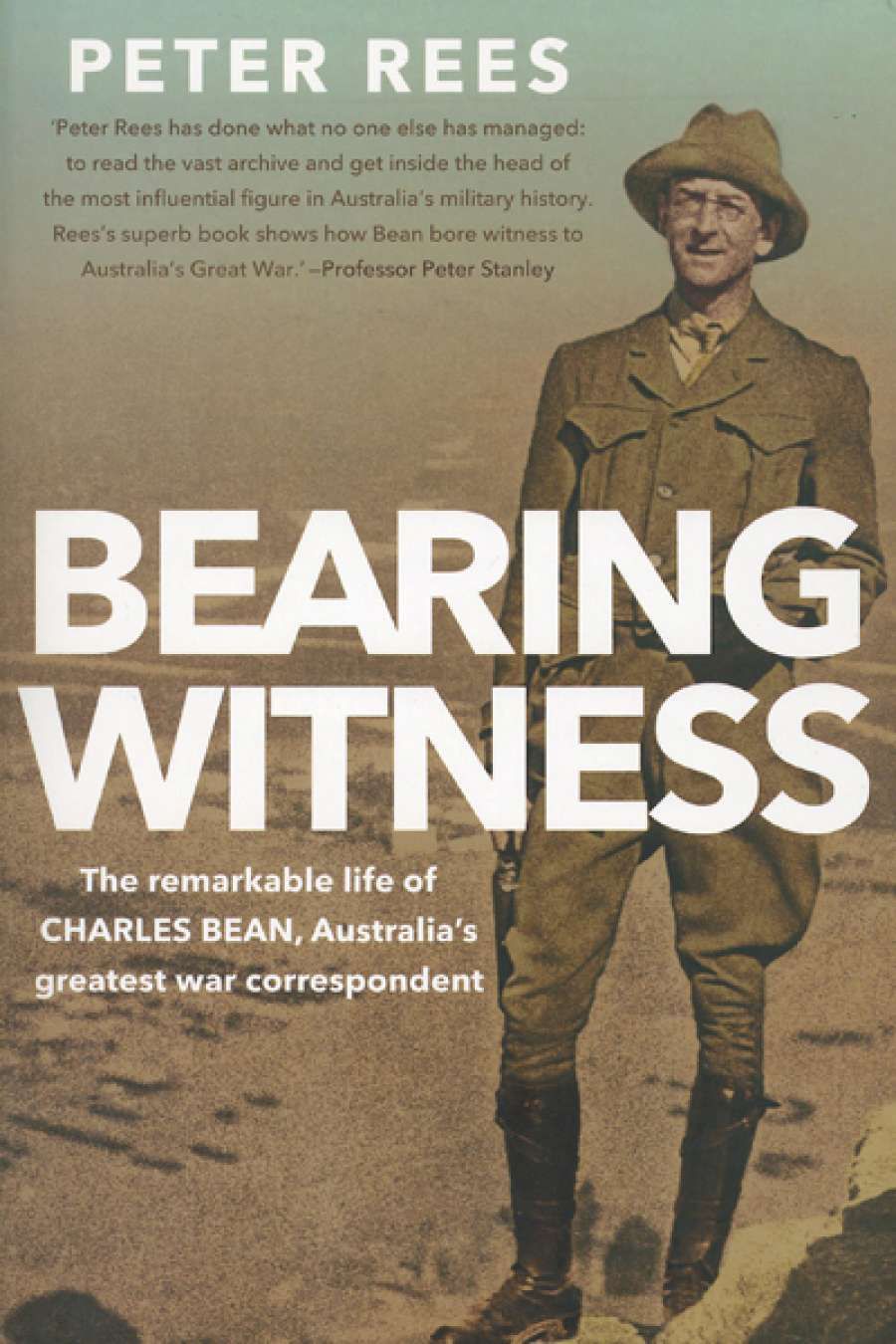

- Custom Article Title: Geoffrey Blainey reviews 'Bearing Witness' by Peter Rees

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Book 1 Title: Bearing Witness

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Remarkable Life of Charles Bean, Australia's Greatest War Correspondent

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 567 pp, 9781742379548

The first academic historian of a younger generation who spoke highly of Bean was probably Ken Inglis, and that was in the mid-1960s. When Bean, as an old man, died in Sydney in 1968, he was praised more by leading politicians and soldiers than by intellectuals, and more by right-wing rather than left-wing citizens. And yet in recent years nationwide tributes have been plentiful.

A Bathurst boy, Bean was educated mostly in England before returning to New South Wales, where he became a star reporter on the Sydney Morning Herald. In 1914 he was the government’s choice as the war correspondent who would accompany the Australian soldiers and cavalry horses on their voyage to the war zone in the eastern Mediterranean. Tall and lean, he was easily identified on the battlefields of Turkey and France, for he was unarmed, wore pince-nez glasses, and carried ‘a telescope slung over a shoulder and a notebook either in hand or protruding from his coat pocket’. He was fearless or close to it, risked his life many times, sometimes carried water to dying soldiers, and, when wounded, refused to go to the hospital ship that was usually anchored near the Gallipoli beaches. He was recommended for a Military Cross, but as a civilian he was ineligible.

Bean wrote six key volumes in Australia’s official history of the war. It is fascinating to learn of the bumpy ride of his first typescript. The Sydney publisher was not impressed with Bean’s jerky prose, erratic grammar, and some of his judgements. Bean, as we all probably would, resented the criticism and thought of resigning as author.

Eventually he agreed that T.G. Tucker, retired professor of classics at Melbourne University – a dandy known for his pearl tie-pin and handsome gloves – should act as his editor. The book, while remaining Bean’s work in essence, was transformed before it finally appeared in 1921 as The Story of Anzac. Year after year, Bean mastered his craft while quietly expressing gratitude for Tucker’s backroom skills. Today, if an anthology of twenty outstanding excerpts about Australian history were published, Bean would probably be represented.

Peter Rees’s creditable biography of Bean is intensely revealing or suggestive about the personalities and clashes of the Australian and British generals, especially Monash, Brudenell White, Rosenthal, Gellibrand, Haig, Birdwood, and Hamilton. Bean the war correspondent met Monash the general before either could be called great. They were still apprentices at their craft – and had not even seen one minute of warfare – when they first met in Egypt, a few months before the landing at Gallipoli. They had dinner together in a hotel in Alexandria on 31 January 1915. Rees describes the meeting as ‘unfortunate’: Bean was suffering from stomach trouble and was longing for the meal and conversation to end. In Cairo, Bean for the first time watched Monash training his brigade. He was impressed by the lucid way Monash explained what his officers had to do in the course of the manoeuvre, and by the ‘extreme thoroughness’ with which he had worked over every detail of his plans.

Arthur Bazley and John Balfour sort through Charles Bean's private diaries (Australian War Memorial)

Arthur Bazley and John Balfour sort through Charles Bean's private diaries (Australian War Memorial)

At Gallipoli, Monash landed on the second day. In his first major military attack, on the hill called Baby 700, Monash was somewhat let down by a British general, and perhaps by New Zealand and British forces; and the death toll of his own troops was heavy. ‘The attack was a debacle,’ Rees concludes. From Bean’s own private diary and the writings of modern military historians, it seems that Monash also shared some of the blame. But his brigade, as Bean pointed out publicly, went on to defend the most difficult sector at Anzac Cove for more than a month.

‘Charles Bean is now seen as one of the classiest journalists and historians Australia has produced’

Bean was a reluctant admirer of Monash. He privately noted the criticisms voiced around Anzac Cove that Monash, compared to other leaders, was not often seen in person at hazardous points on the front line. Monash, however, had valid justification for his reluctance to be killed by a sniper’s bullet.

The relations between the two Australians were bound to be uneasy. Bean had to report on the fighting, but his sentences had to face irritating censorship from above. The newspaper readers in Australia must not be told the whole truth. Bean was shocked to learn that, owing to censorship, the names of only fifty Gallipoli casualties had been published in the Australian press when ‘more like 5000’ had occurred in one division alone.

Monash felt that his own exploits were not appreciated by readers at home. Using a side door, he quietly sent his version of events to the Melbourne Argus, which rewrote and published them without indicating that he was the prime source. Peter Rees, himself an experienced newsman, is illuminating on the way war news flowed or was halted.

‘Bean the war correspondent met Monash the general before either could be called great’

You come to realise that Monash was a polymath. He could do almost everything and do it well. He could have been a first-class reporter, but as a general he had to persuade others to use his words. Always he wanted to win, and to be known as the winner. While this did not win him a thousand friends, it was surely a key to his success as a general and a military thinker.

Back in Australia, Bean and Monash shared phases of goodwill as well as disagreement, and yet the greatness, as well as the faults, of both men, so different in background and personality and wartime roles, are emerging in a tantalising way by the time the book closes.

Rees classes Charles Bean as Australia’s finest war correspondent and the shaper of a national legend: ‘He did not fire a bullet but left a priceless legacy.’ This book is more than a biography and will be viewed as one of the most readable accounts of Australia’s military campaigns in World War I.

Comments powered by CComment