- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Colin Nettelbeck reviews 'Suspended Sentences' by Patrick Modiano translated by Mark Polizzotti

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

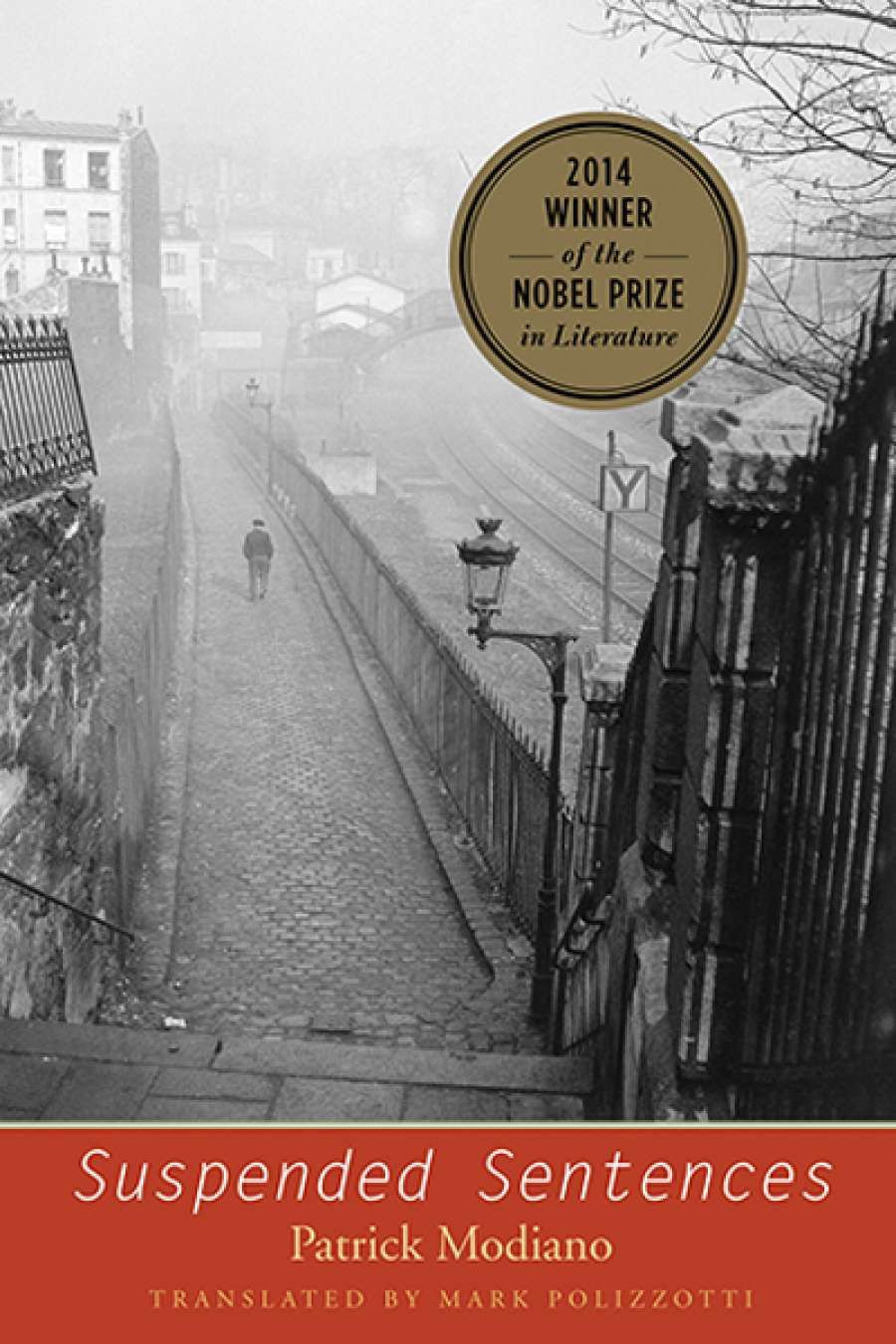

- Book 1 Title: Suspended Sentences

- Book 1 Subtitle: Three novellas

- Book 1 Biblio: Yale University Press (Inbooks), $33.99 pb, 226 pp, 9780300198058

One puzzle posed by the anthology is why the pieces are not presented in the chronological order of their original writing and publication. Afterimage (Chien de printemps) comes first here but was the last to appear (1993); Suspended Sentences (Remise de peine, 1988) and Flowers of Ruin (Fleurs de ruine, 1991) are likewise rearranged. Chronology is not perhaps an absolute principle to follow, but in the absence of any obvious reason for change, one can only wonder about the motivation.

Modiano’s early work, including his scenario with the film director Louis Malle for the masterpiece Lacombe, Lucien (1974), was centred on France’s experience during the German Occupation. It has been credited by historians as a significant factor in opening up that period to new scrutiny. He was identified as a kind of prodigal genius able to channel a whole nation’s repressed and uncomfortable memories. His later writing, while never without rumbling echoes of the Occupation period, turns around more general themes of uncertainty and loss: uncertainty of memory, both individual and collective; uncertainty of identity and purpose; loss of connection with the places and people that might have provided greater meaning or resolution.

Patrick Modiano (photograph by A. Mahhmoud)

Patrick Modiano (photograph by A. Mahhmoud)

Each of the three novellas in this collection plays on these themes. Suspended Sentences recounts an episode of the narrator’s dislocated childhood in the Paris suburbs, in which he and his younger brother (who will soon die) are abandoned by their absent parents to the care of a motley group of suspect characters. Childish playfulness mixes with sinister undertones in an edgy and disturbing fashion. Flowers of Ruin and Afterimage are set in the 1960s, when the narrator, around the age of twenty, is working on his first novel, and is at the same time caught up in a myriad of investigations of identities true and false, simultaneously criss-crossing the different neighbourhoods of Paris and the different eras and circumstances through which the people he meets have lived. These include the murky figure of his Jewish father, who narrowly survived a black-marketeering career during the Occupation, and whose friends included the riff-raff of the French Gestapo. But there is also the much more attractive figure of the photographer Francis Jansen, a student and colleague of Robert Capa’s: the narrator volunteers to put order into Jansen’s vast collection of photos, only to be frustrated when Jansen disappears forever, perhaps to Mexico. Many ghosts drift in and out of the narrative, including ephemeral girlfriends and other women whose functions and personalities remain immersed in ambiguity.

‘He was identified as a kind of prodigal genius able to channel a whole nation’s repressed and uncomfortable memories’

With its emphasis on memory and the art of writing, it is not surprising that Modiano’s writing should so often have been compared with that of Proust. But such a comparison requires caution. Across its immense length and its meanderings, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time has a unity of form that expresses unfailing – if not absolute – faith in artistic achievement. Modiano’s world belongs to a later, more fragile phase of our human civilisation, where too many things have been broken or have broken down for any art to have such confidence. Kaleidoscopic and knowingly tentative, his works take us past nostalgia for lost youth or easier times, into the ontological shadows that haunt our species.

The counterpoint to that darkness is a writerly sureness that has grown ever stronger over time. Modiano’s prose is deceptively simple in its gossamer spareness and musicality. On closer inspection, one can see that the apparently classical prose is infused with careful borrowings from other forms: painting, photography, and especially cinema. Modiano has created contemporary writing that can survive in the audio-visual age without being consumed by it, as well as a form of expression that creates enough distance for a good measure of wry humour. With the likes of the Polizzotti translations, English-language readers will henceforth have readier access to the challenges and charm of Modiano’s chiaroscuro literary universe. It’s about time.

Comments powered by CComment