- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

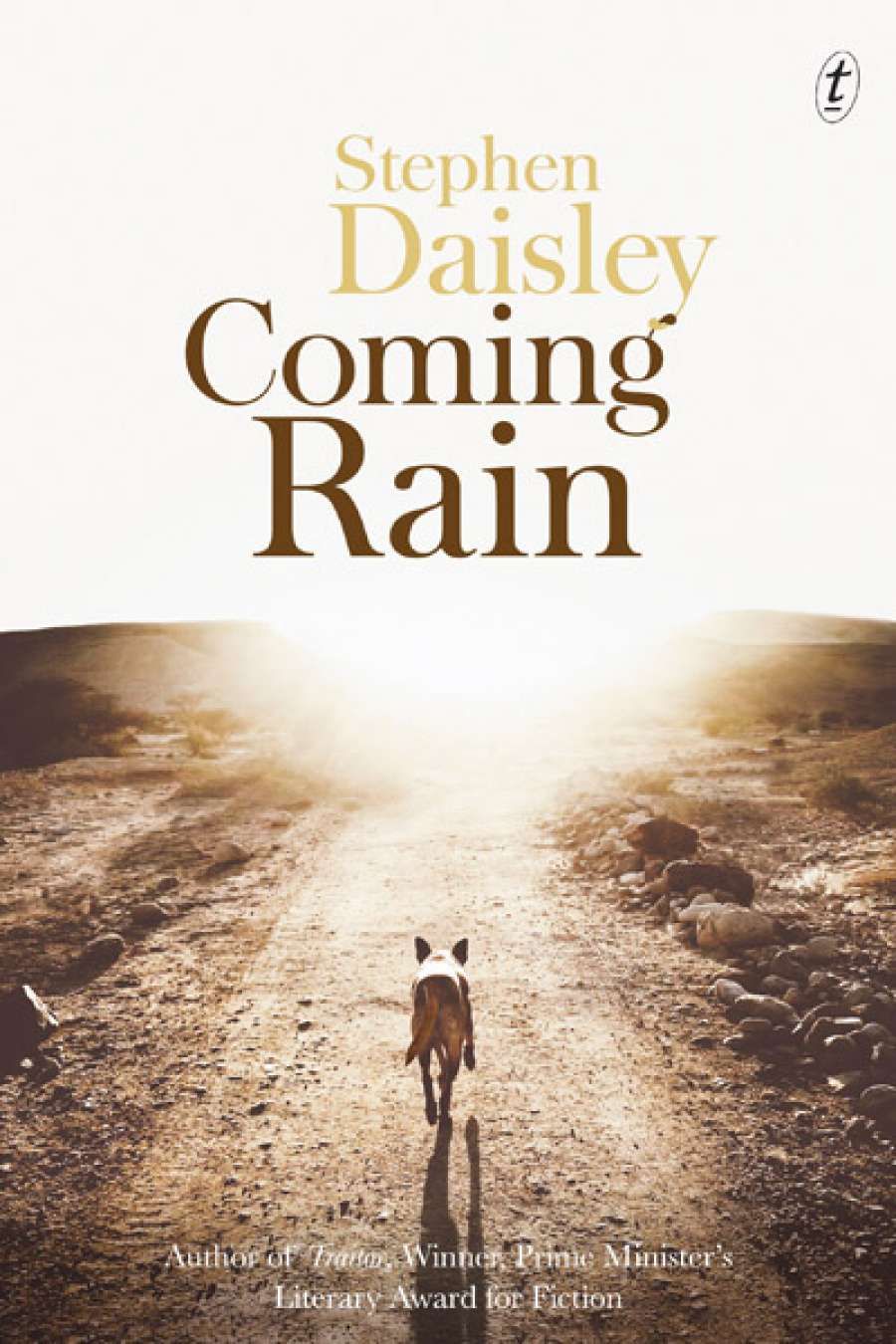

- Custom Article Title: David Whish-Wilson reviews 'Coming Rain' by Stephen Daisley

- Book 1 Title: Coming Rain

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 270 pp, 9781922182029

Stephen Daisley (photograph by Darren James)

Stephen Daisley (photograph by Darren James)

When Clara Drysdale, the daughter of the boss, meets Lew, however, the younger man’s head is turned. She is a young woman of considerable charm, of a private-school upbringing and therefore an unlikely match for the perennially barefoot Lew. As well as her beauty, Lew is impressed by the devotion of her animals to their mistress, and her tenderness towards her animals. The pair embark upon a gentle courtship, albeit one discouraged by Painter and forbidden by the boss, John Drysdale (who resembles a subject in a Russell Drysdale painting, with his ‘Chains of wet dust in the wrinkles of his neck. His Adam’s apple moving up and down as he swallowed. The burnt side of his face had white zinc cream on it. Some dust had stuck to the cream. Like the colour of bloodwood through the zinc.’) The pair find privacy at a local waterhole, and the intimacy they discover there is part of an important and unspoken paradox – they are on stolen land, in fact the site of a massacre, and yet while there is no reconciling or healing what cannot be understood, it’s precisely the space and absence of others that allows them to be as natural and free as children, where their ‘overwhelming desire for each other was the desire to be alive’.

‘For this reviewer, it’s been a long five years since the publication of Stephen Daisley’s Traitor (2010)’

In counterpoint to this narrative is the parallel story of a dingo bitch on the run from Abraham Smith, a dog-shooter also responsible for ‘cleaning the place up’ of its Nyungar inhabitants. This second narrative strand suggests an ancient re-enactment of one of the archetypal life-cycles of the South-West landscape, in spite of the intrusion of the ‘monstrous presence’ of the European farmers, their crops and animals. Acute in her observations, her literally ground-level perspective also provides a closer and symbolically indigenous reading of the landscape, represented by way of a keenness of sense and a close understanding of place passed down over hundreds of generations. Even as her relationship with a wounded young male dingo mirrors Lew and Clara’s developing relationship, the whites still see the dingo as they once saw the black – as inherently savage, unable to be tamed, still subject to rule .303. The narrative tension that her struggle to survive brings to this moving and brilliant novel is considerable, particularly as it heads towards a conclusion that in its tragedy and tenderness is perfectly in keeping with both the ‘desire to be alive’ and the colonial logic and history of the South-West frontier.

Comments powered by CComment