- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Kevin Rabalais reviews 'The Wonder Lover' by Malcolm Knox

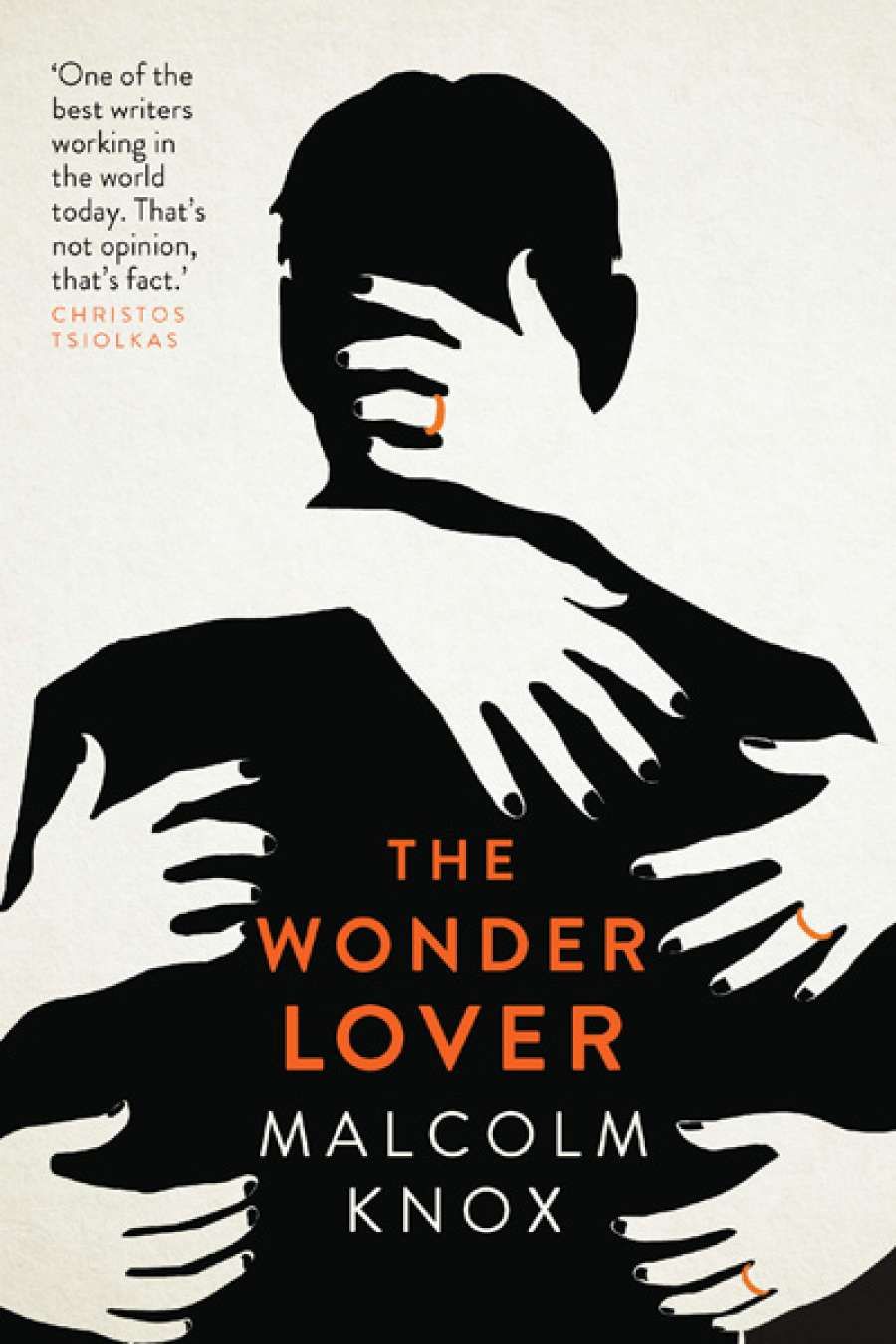

- Book 1 Title: The Wonder Lover

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 374 pp, 978176011259

The first notable detail is the first-person plural voice that serves as the novel’s narrator. Through this collective voice, Knox establishes a main character much closer to that of Scheherazade than the washed-up surfer who narrates The Life. ‘When we were very young, our father sat on the end of our bed to unload his sack of stories,’ Knox writes at the outset of The Wonder Lover. This father, John Wonder – ‘Authenticator-in-Chief for humankind’s last word on extraordinary fact’– tells his children stories, and they are always true. As his position dictates, Wonder orders his world through facts. One fact: he maintains not one but three families, each an echo of the others. With each of his three wives, spread over as many cities, he has two children – a boy and a girl. ‘They had our names, Adam and Evie,’ Knox writes. ‘Adam and Evie Wonder. They attended, as we did, the free government school nearest the house. Our father and our mothers could not afford to be choosy. These children, Adam and Evie Wonder, are also us and we are they.’

In attempting to understand their father, the children relay his story, occasionally delving into the thoughts of other characters Wonder meets on his travels. We learn that, in each of his lives, Wonder ‘had an office that mirrored, in every respect, down to the carpet and the wall paint and the furnishings, his offices in the first two cities … Once one thing varies, he liked to say to his staff, no matter how trivial-seeming, the whole edifice will fall.’

‘Malcolm Knox has established himself as one of the most ambitious and exciting fiction writers at work in Australia’

Wonder’s work includes ‘personally verifying Pi to one thousand decimal places’ and measuring ‘the world’s standard size for eggs, envelope sizes, boxing weight divisions …’ Such fact-checking begins to crumble after he sees Cicada Economopoulos (‘Every man– literally every one– stared at her’) and plans to authenticate her as the world’s most beautiful woman. Despite convincing three other women to marry him and have his children, this wonder lover displays little or no emotion. He remains, as the children note, a ‘dry papery man without a hint of sex appeal, that calm scholarly numericist who lived not in the world of passions but in the world of trivia’. Falling in love with Cicada, therefore, becomes the ‘calamity’ that resides at the centre of the novel.

Malcolm Knox

Malcolm Knox

When Wonder leaves the terra firma of his work, he becomes further removed from himself and everyone around him, even drier than the man his children describe. Knox clutters the narrative with repetitious detail. This includes saying things in multiple ways without adding value to the overall narrative or taking us deeper into the characters’ lives. This results in an over-inflated novel that loses the intensity that it generates in the early pages. Adding to the over-the-top nature of pages littered with exclamation points, these characters ‘spat’ and ‘wept’ and ‘snapped’ their dialogue. While Knox captures, through free indirect discourse, some of the easy phrases in which his characters think, the narrative trills with well-worn expressions. Here, the narrator reflects on Wonder’s first two wives: ‘What they didn’t know couldn’t hurt them.’ Or, within a single paragraph: ‘that was all it needed to boil down to’ and ‘let’s get to the bottom line here’, while several pages later a character ‘breathed a sigh of relief’.

It is a testament to Knox’s talent and creativity that we remain, throughout, excited by the ambition and potential of this novel. We marvel at this writer who stretches himself, and for that reason we read much of The Wonder Lover in awe of its creator’s inventiveness. Late in the novel, Wonder’s children note that their father sometimes loses the threads of the stories he tells. Knox never mislays the thread. However, the novel’s loose language and the filler repetition forces us to wish for a tighter grip.

‘he maintains not one but three families, each an echo of the others’

Since the publication of his début novel, Summerland (2000), Malcolm Knox has established himself as one of the most ambitious and exciting fiction writers at work in Australia. A seasoned journalist, recipient of two Walkley Awards – one for his work, with Caroline Overington, in the exposé of Norma Khouri – and prolific author of diverse non-fiction works that include I Still Call Australia Home: The Qantas Story (2005), Scattered: The Inside Story of Ice in Australia (2008), and Bradman’s War (2012), Knox began his life as a novelist by paying homage to a twentieth-century master. While Summerland uses Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915) as its springboard, Knox proves unflinching in the subjects that consume him there and which continue to do so: namely, Australian identity and masculinity.

Knox’s novels, which include his wondrous follow-up, A Private Man (2004), as well as Jamaica (2008) and The Life (2011), are unlike any in contemporary Australian fiction. Given the close attention that all of his fiction pays to Australia, the often-unidentifiable settings of The Wonder Lover, along with the ambition that it announces in its early pages, make this latest novel a startling addition to Knox’s body of work. The art of the novel is always a high-wire act; here we find the author at work without a net.

The first notable detail is the first-person plural voice that serves as the novel’s narrator. Through this collective voice, Knox establishes a main character much closer to that of Scheherazade than the washed-up surfer who narrates The Life. ‘When we were very young, our father sat on the end of our bed to unload his sack of stories,’ Knox writes at the outset of The Wonder Lover. This father, John Wonder – ‘Authenticator-in-Chief for humankind’s last word on extraordinary fact’ – tells his children stories, and they are always true. As his position dictates, Wonder orders his world through facts. One fact: he maintains not one but three families, each an echo of the others. With each of his three wives, spread over as many cities, he has two children – a boy and a girl. ‘They had our names, Adam and Evie,’ Knox writes. ‘Adam and Evie Wonder. They attended, as we did, the free government school nearest the house. Our father and our mothers could not afford to be choosy. These children, Adam and Evie Wonder, are also us and we are they.’

‘the often-unidentifiable settings of The Wonder Lover, along with the ambition that it announces in its early pages, make this latest novel a startling addition to Knox’s body of work’

In attempting to understand their father, the children relay his story, occasionally delving into the thoughts of other characters Wonder meets on his travels. We learn that, in each of his lives, Wonder ‘had an office that mirrored, in every respect, down to the carpet and the wall paint and the furnishings, his offices in the first two cities … Once one thing varies, he liked to say to his staff, no matter how trivial-seeming, the whole edifice will fall.’

Wonder’s work includes ‘personally verifying Pi to one thousand decimal places’ and measuring ‘the world’s standard size for eggs, envelope sizes, boxing weight divisions …’ Such fact-checking begins to crumble after he sees Cicada Economopoulos (‘Every man – literally every one – stared at her’) and plans to authenticate her as the world’s most beautiful woman. Despite convincing three other women to marry him and have his children, this wonder lover displays little or no emotion. He remains, as the children note, a ‘dry papery man without a hint of sex appeal, that calm scholarly numericist who lived not in the world of passions but in the world of trivia’. Falling in love with Cicada, therefore, becomes the ‘calamity’ that resides at the centre of the novel.

When Wonder leaves the terra firma of his work, he becomes further removed from himself and everyone around him, even drier than the man his children describe. Knox clutters the narrative with repetitious detail. This includes saying things in multiple ways without adding value to the overall narrative or taking us deeper into the characters’ lives. This results in an over-inflated novel that loses the intensity that it generates in the early pages. Adding to the over-the-top nature of pages littered with exclamation points, these characters ‘spat’ and ‘wept’ and ‘snapped’ their dialogue. While Knox captures, through free indirect discourse, some of the easy phrases in which his characters think, the narrative trills with well-worn expressions. Here, the narrator reflects on Wonder’s first two wives: ‘What they didn’t know couldn’t hurt them.’ Or, within a single paragraph: ‘that was all it needed to boil down to’ and ‘let’s get to the bottom line here’, while several pages later a character ‘breathed a sigh of relief’.

It is a testament to Knox’s talent and creativity that we remain, throughout, excited by the ambition and potential of this novel. We marvel at this writer who stretches himself, and for that reason we read much of The Wonder Lover in awe of its creator’s inventiveness. Late in the novel, Wonder’s children note that their father sometimes loses the threads of the stories he tells. Knox never mislays the thread. However, the novel’s loose language and the filler repetition forces us to wish for a tighter grip.

Comments powered by CComment