- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Family wounds

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the keenest childhood memories of David Meredith, narrator of George Johnston’s novel My Brother Jack (1964), is of the hall of his parents’ suburban home in Melbourne. It was full of prostheses, the artificial limbs of servicemen returned, maimed, from the Great War. The men are friends and former patients of Meredith’s parents. Her mother was a nurse, her father served in the First AIF. The scant historical regard that has been paid to these damaged men, and to their families, is rectified by Marina Larsson’s brilliant study of Shattered Anzacs. Her subject is the cohort of revenants who returned to Australia after the war – their bodies ruined, shell-shocked, infected with venereal disease and tuberculosis – and the families, institutions and government bureaucracies into whose hands they fell.

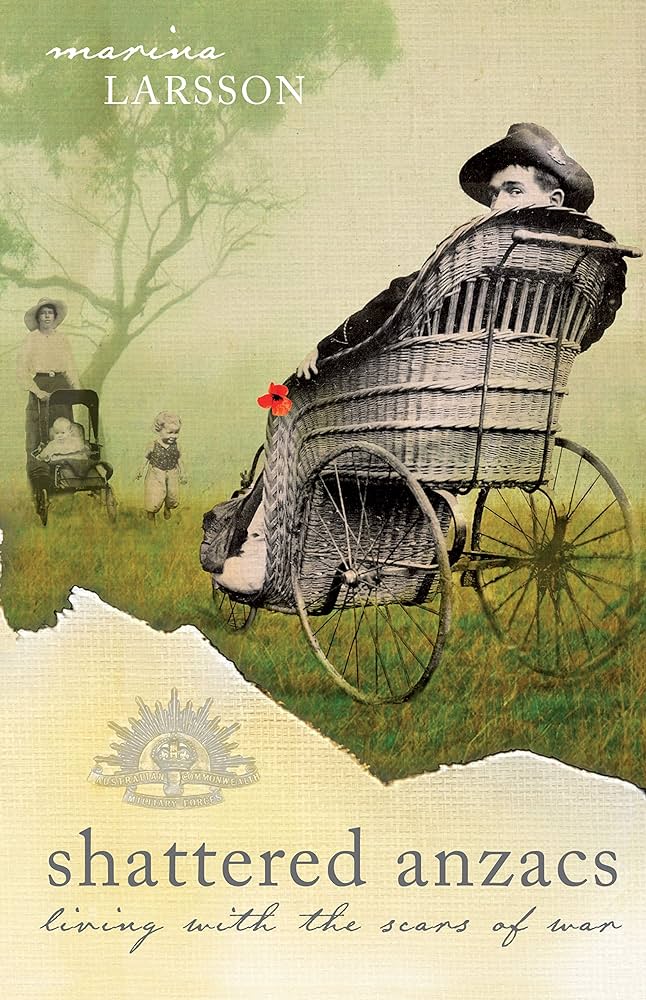

- Book 1 Title: Shattered Anzacs

- Book 1 Subtitle: Living with the scars of war

- Book 1 Biblio: University of New South Wales Press, $39.95 pb, 320 pp, 9781921410550

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In constructing Shattered Anzacs, Larsson drew on extensive official material, but she also used ‘oral history informants’, eleven children of Great War veterans. Their testimonies contributed to an essential part of her inquiry: ‘Family members of disabled soldiers became intimate witnesses to the devastating impact of the war on the human mind and body.’ The family ‘became a key site of repatriation’. This, of course, is not in accord with the celebration through the Anzac Legend of how a nation killed its way into history through war. As Larsson crucially emphasises, ‘the history of war disability ... is not self-evidently a national story: there is also a family story to be told’.

First, though, Larsson provides a broad statistical picture. Whatever David Meredith’s recollection, fewer than 3300 servicemen returned to Australia missing a limb. By contrast, 55,000 members of the First AIF (seventeen per cent) contracted venereal disease. Improvements in medicine meant better survival rates for the wounded. In turn, that meant more disabled soldiers. By 1920, 90,000 of them were receiving war disability pensions. When World War II began, 77,000 veterans of the Great War were still living with a war disability. The harrowing ways in which such circumstances affected many more than this – the members of the servicemen’s families and communities – is a key element of Shattered Anzacs. ‘War wounds’, as the title of the first chapter states, became ‘family wounds’.

The freshly wounded, far from home, often self-censored their accounts of their condition, both ‘to protect and manage the emotional needs of relatives’ and out of a ‘patriotic culture of stoicism’. But what was the soldier telling those at home who is pictured writing a letter with the stumps of his wrists, in a pose of grisly good cheer? Such ‘brave disabled warriors’ – ‘changed’ men – were given a public welcome that praised their sacrifices, then a second, private one back into the family realm. Besides their families’ adjustments to their blindness, deafness and personalities changed by shell shock, veterans had to find ways to make ends meet. Pensions from the Repatriation Department were often matters of long and bitter dispute. Charity was a second line of support. Jobs were hard to find, or hold. Of the thousands who joined the mainly ill-fated rural soldier settlement schemes, an astonishing forty per cent had the extra burden of being disabled. Others, lacking skills and education, found work as lift drivers, as, after the next war, would Alf Cook in Alan Seymour’s The One Day of the Year (1960).

Shattered Anzacs is a partial, harrowing history of the interwar years in Australia. Larsson maps the shrinking social world of the disabled soldier. If they were among the 3000 with ‘war-related tuberculosis’, their isolation was the more complete but so, unhappily, was the likelihood of ‘intra-family transmission’ of the disease. Moreover, whatever their wartime heroics, tuberculosis sufferers were perceived as ‘a threat to the health of the nation’ – this in an Australia ridden by fears of contagion by disease and ideas from without and within.

Larsson addresses much else: for example, the pressure to separate the shell-shocked from the civilian insane. Female relatives of the disabled could find some solace meeting others in like circumstances at the Friendly Union. By the 1930s ‘the children of disabled soldiers ... played a more prominent role in their fathers’ lives’. Larsson’s cardinal arguments are that ‘the war “disabled” the lives of kin as well as soldiers’; that the notorious taciturnity of veterans of the Great War may in large measure be due to the physical and mental ailments of so many, which enforced retreat to their families and to institutions. Larsson insists, in ending this impressive and compassionate revisionist study, that we need to think not only, as Anzac bids us, of the ‘fallen’, but ‘to reconceptualise the spatial and temporal boundaries of “war death”’, the better to understand the continuing sacrifices, mostly in private, of tens of thousands of veterans and their families.

Comments powered by CComment