- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Martyn Lyons reviews 'In These Times' by Jenny Uglow

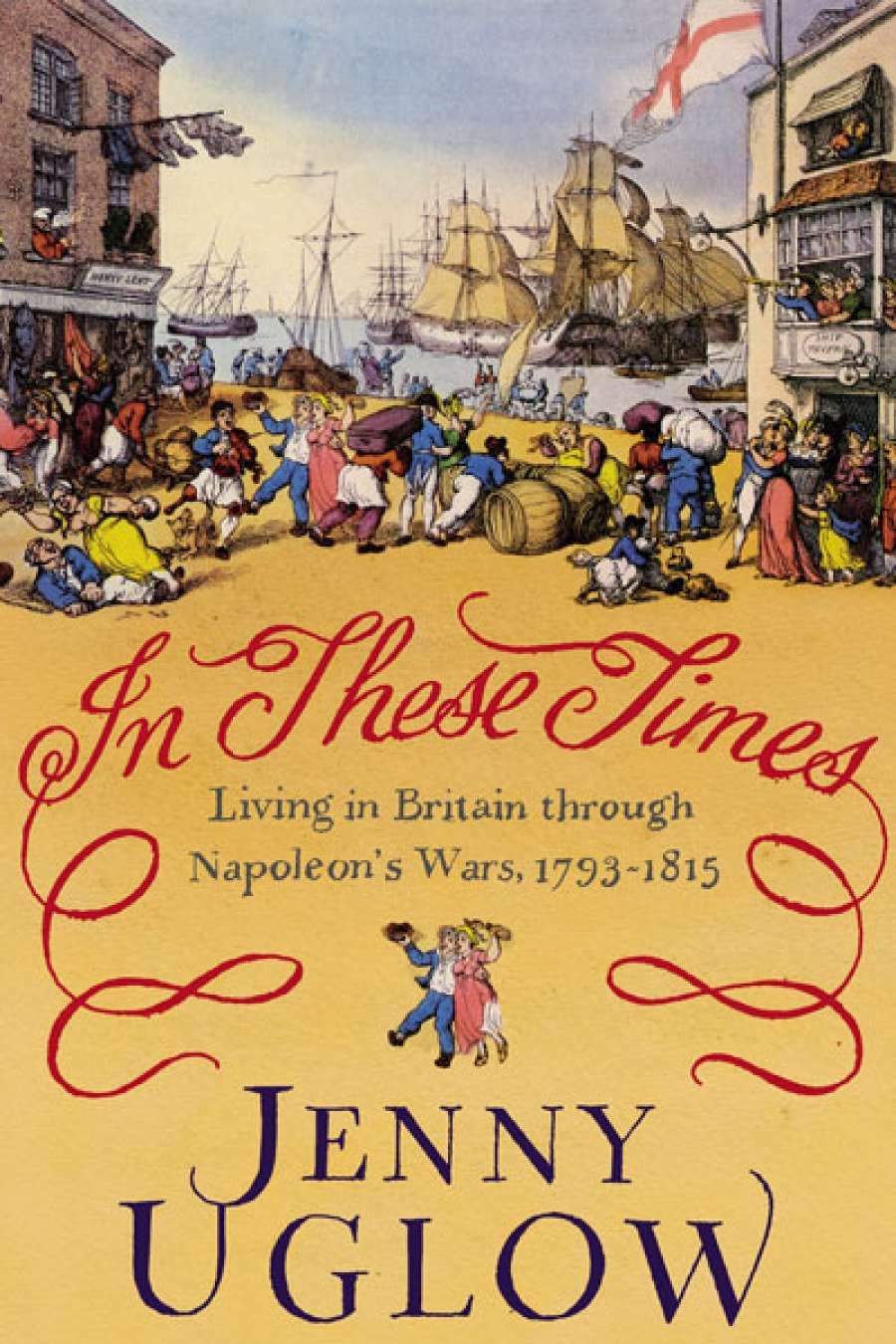

- Book 1 Title: In These Times

- Book 1 Subtitle: Living in Britain Through Napoleon's Wars, 1793-1815

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber & Faber, $49.99 hb, 751 pp, 9780571269525

Uglow favours the most articulate members of her cast, referring frequently to literary figures, like Wordsworth becoming increasingly conservative and nauseatingly patriotic, gloomy Coleridge with his West Country accent, Walter Scott drilling with the militia, not yet the author of the Waverley novels, which would make him not just a British bestseller, but an international literary superstar. Not to mention Jane Austen’s scatty young women flirting with anything in uniform. Byron’s caustic criticism of the establishment is a welcome antidote to this literary sabre-rattling.

The fear of domestic rebellion was compounded by anxieties over a French invasion, for which Britain was ill-prepared. Napoleon’s Army of England drilled menacingly across the Channel at Boulogne in 1804–05. Of course, Britain was invaded: the French landed a force in Ireland in 1798, the year of the revolt of the United Irishmen, and a provisional government was briefly set up in Connaught. Uglow makes surprisingly little of this story, which dented French illusions: Ireland may have been Britain’s weakest link, but her people were quite unreceptive to foreign brands of republicanism.

From a British point of view, Britain’s war was a story of military disasters and naval victories, and Uglow effectively recounts popular responses to both. Expeditions to Flanders in 1794 and again in 1809 ended in fiasco. But victory at sea over the Dutch fleet (Battle of Camperdown) in 1797 was followed by Nelson’s exploits at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Nelson mania was at its height. After Trafalgar in 1805, Nelson’s body was brought back to England pickled in a brandy cask for his state funeral and burial in St Paul’s Cathedral. There was, wrote Charles Lamb, ‘a great Aquatic bustle’.

Private drilling by Thomas Rowlandson (1798)

Private drilling by Thomas Rowlandson (1798)

This was a global war, as Uglow makes clear, fought in Continental Europe, the Mediterranean, and the Baltic, but also in the Caribbean, South America, the Middle East, India, and the Indian Ocean. Army contractors made a fortune. A vast slaughterhouse at Deptford was the destination for Welsh and Scottish drovers, while the armed forces devoured Irish butter, Cheshire salt, and Somerset cheese. The iron foundries of South Wales churned out cannon, bayonets, and munitions. Even Napoleon’s army contributed to British profits: the French army in Poland, we are told, wore boots made in Northampton and greatcoats fashioned from Yorkshire wool. Uglow is not a traditional military historian, but she devotes interesting pages to recruiting, the press gang, and army suppliers.

‘The British were an unruly people, as Jenny Uglow’s book on British life during the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars testifies’

Napoleon imposed a Continental Blockade in an attempt to dry up British exports to Europe. Exports still got through since customs officers could always be bribed, and goods were smuggled through Malta or Greece. Napoleon could not touch British exports to India and South America. But there was a glut of unexportable textile goods and a serious economic crisis in 1810–11, in which the followers of Ned Ludd protested against their dire working conditions by smashing machinery. How close did Britain really come to a revolution in these conflicted years? Uglow is not prepared to consider the question, and her whirlwind account lacks analytical reflection on the world she describes.

Good leadership was certainly not the reason why Britain got through these decades of war, invasion threats, and seething rebellion. No Churchillian figure emerged to unite the country. The king himself was periodically mad, and the politicians usually at one another’s throats. In 1809, two brilliant cabinet ministers (Canning and Castlereagh) even fought a pistol duel with each other.

‘Uglow presents a panoramic view of British society at war’

The country ran up a massive debt, much of the money being raised to subsidise Britain’s Austrian allies in the land war against the French. Britain’s finances survived because William Pitt created a Sinking Fund with debt repayments in mind, and created one of the war’s most lasting side-effects – he invented income tax. Wellington’s armies in Spain needed to be paid and equipped, and for this Nathan Rothschild’s family connections were invaluable. Wellington’s famous Spanish victories against Napoleon relied on men he called ‘the scum of the earth’, but the Peninsular War was won with Rothschild money.

These years saw an evangelical revival, which bore fruit in the abolition of the slave trade in 1809. Hannah More produced her Cheap Repository Tracts – penny pamphlets warning against the dangers of drink, idleness, atheism, and rebellion. Millions of copies were distributed free to prisons, hospitals, and church congregations, thus constituting the first instance of large-scale junk mail.

Uglow stresses that throughout the war normal life continued its daily grind, at least at a certain level of society. The London theatre season continued, balls were given, libertines duelled, gamblers threw away astronomical sums of money, children died of epidemic disease. Tourists continued to visit Weymouth, Brighton, or the Lake District, but they also went to see mines, factories, and mills, for these marvels of industrialising Britain were still novelties. But Uglow answers few of the questions raised by her profuse material, because she does not ask any. War had meant the end of hopes for reform of Britain’s corrupt political system, as all was swallowed up in a tide of patriotism, and any democratic ideas were dismissed as pro-French and therefore treasonable. Uglow suggests that people shared a new sense of Britishness as a result of fighting Napoleon for twenty years, but she gives plenty of evidence of a divided nation teetering on the brink of its own revolution, ruled by a corrupt élite, a mad king, and an unreformed Parliament.

Comments powered by CComment