- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Catriona Menzies-Pike reviews 'The Last Pulse' by Anson Cameron

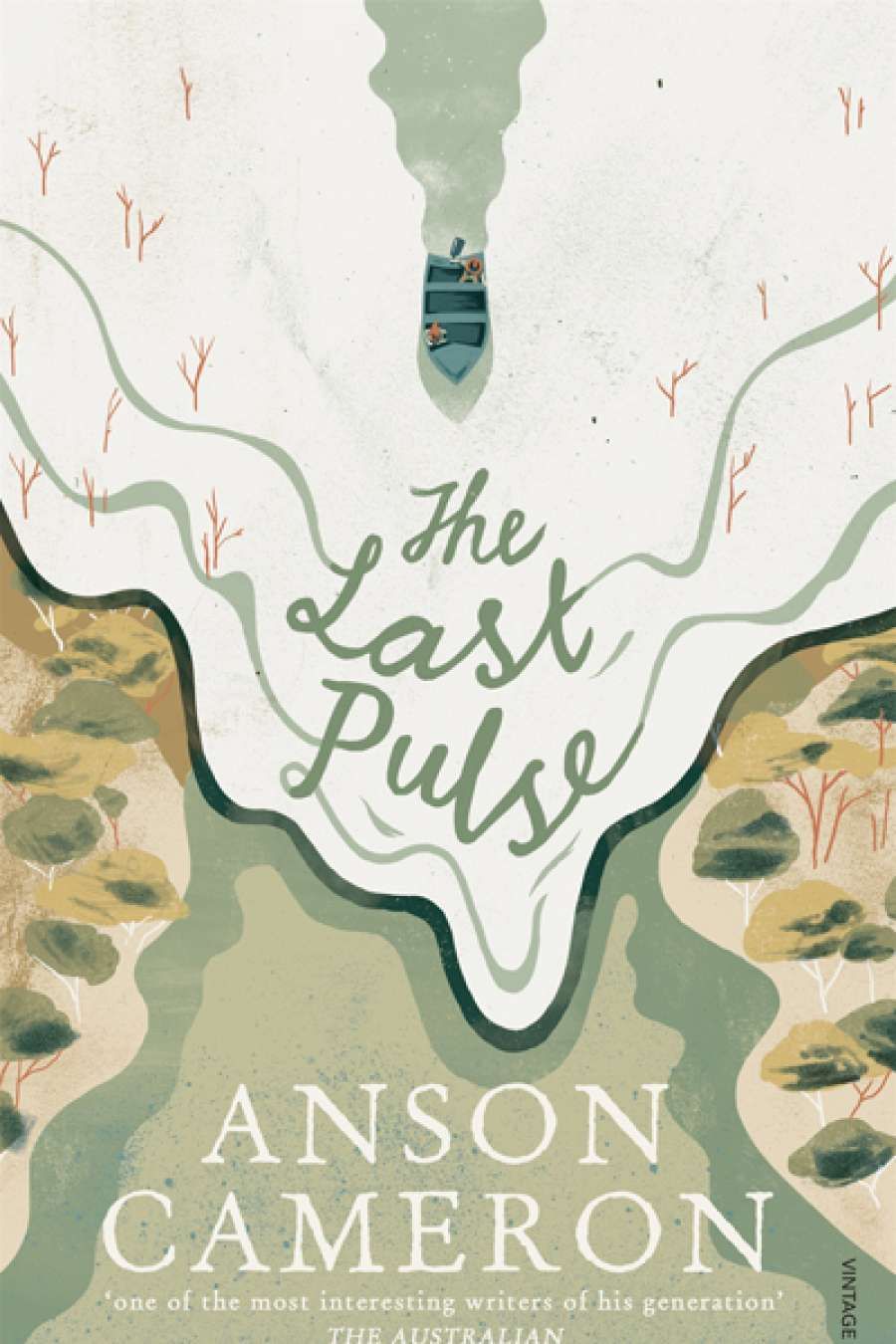

- Book 1 Title: The Last Pulse

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $29.99 pb, 273 pp, 9780857984982

The characters are fictional; so are most of the places that Merv and Em visit. The toxic water politics of the Murray–Darling Basin, however, keep this floating vengeance comedy anchored in contemporary Australian politics. ‘One man’s dangerous act of terrorism is another man’s inspired act of irrigation,’ Merv assures two Queensland cops. The floodmaker is greeted as a hero by the parched communities replenished by his sabotage, an inversion of the real anger in rural and regional Australia about water management. The novel’s several satirical vignettes of hopeless, heartless policy-makers at work on water allocations and the competing claims of irrigation and environmental protection add up to a bitter-sweet indictment of a broken system. To fix this mess, Merv elects to ‘repatriate’ the water, to let it return home to the dried-out floodplains and riverbeds of the Murray–Darling Basin. Cameron makes merry with his sketches of state identity and doltish bureaucrats, but if the book has a serious point to deliver about water policy it turns on the terrible consequences of failing to think nationally about rivers.

Near the end of his journey, Merv pauses to reflect: ‘[H]ere, when a flood is foretold, we do not build an ark, we procreate, sow seed, burst our banks, drink our fill and feel the full width and splendour of a green season. Here a flood is a pulse in the life of the land.’ The Last Pulse is a joyful celebration of the many lives sustained by the river. For all the knockabout humour, we are never allowed to forget that this is the last pulse of a magnificent natural force. We are reading a threnody for the river system that is also a song of mourning for the souls lost to the drought. The Last Pulse is haunted by many ghosts. Merv makes Em participate in a call-and-response game that is a litany of the casualties of the drought. When Merv asks, ‘Where is David Birrell now’, Em knows to answer, ‘His vines died. He gassed himself from money trouble.’ For these two riverine outlaws, the name of the most painful casualty of the drought is rarely spoken: Jana, Merv’s exhausted wife, Em’s depleted mother. The first scene of the book depicts her suicide, and her absence is deeply felt on the trip: only Bridget Wray, stirred to unfamiliar maternal feelings on this strange cruise, dares mention it. The redemptive flood that Merv unleashes is also a figure for grief, the loss that Em and Merv must ride home.

‘The floodmaker is greeted as a hero by the parched communities replenished by his sabotage, an inversion of the real anger in rural and regional Australia about water management’

Cameron’s feisty wordplay is one of the pleasures of the book, and the distinctive cadences of each character’s speech are carefully transcribed. The town where Merv plants the dynamite, Dillandbundy, a dot on the map somewhere in south-east Queensland, is described thus: ‘Its main street is paved by triangles of shade made by polypropylene sails that palpitate overhead in the breeze like the palates of a thousand toads.’ The language is particularly salty when it comes to Queenslanders, the pantomime upstream villains of The Last Pulse. Cameron enjoys jolting his readers with startling similes; when Merv eyeballs a parking inspector, he has ‘a blinking disgust on his face like he’s staring at a paedophile through fog’. As Em puzzles over the rights and wrongs of blowing up the dam, she remembers Merv telling her that ‘locking the water in that dam is like locking an eagle in a suitcase’. Regrettably, Merv has an ugly line in homophobic banter, and his most crudely drawn caricatures are of gay politicians. Women don’t fare well in Merv’s eyes; drawn from life though the tendency may be, Merv’s frequent conflation of female physiognomy with psychology loses its charm. In a gleeful and inclusive romp, this strikes a dud note.

Does Merv get away with it? Does the flood cleanse the land? Do the cotton-farming villains get their comeuppance? The dénouement of The Last Pulse is over the top and very funny: I won’t spoil the pleasure of the final stages of the The Party Animal ’s journey, save to note that it is extremely satisfying – unless, perhaps, your sympathies lie with the upstream irrigators.

Comments powered by CComment