- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

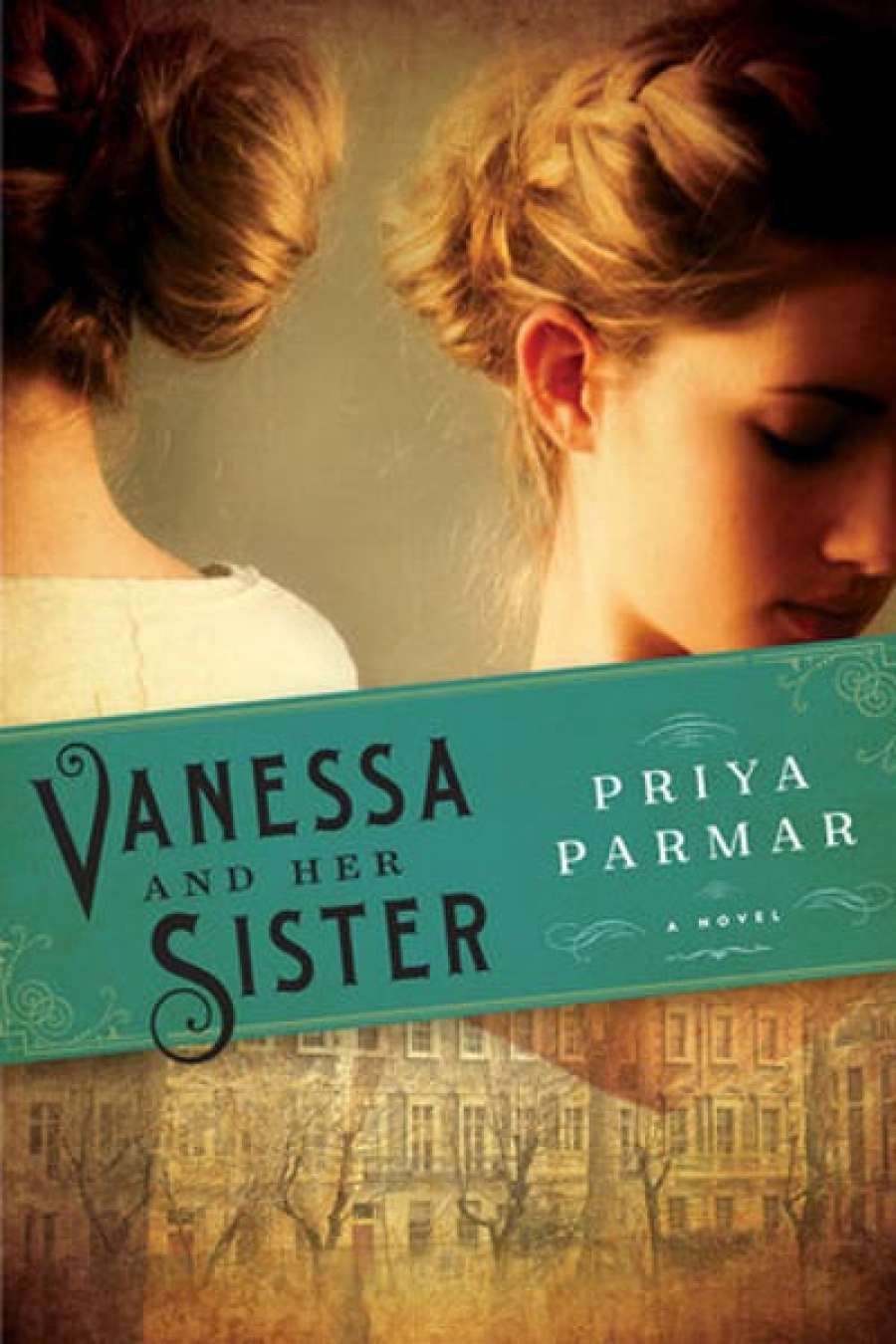

- Custom Article Title: Ann-Marie Priest reviews 'Vanessa and Her Sister' by Priya Parmar and 'Adeline' by Norah Vincent

- Book 1 Title: Vanessa and her sister

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $29.99 pb, 352 pp, 9781408850213

- Book 2 Title: Adeline

- Book 2 Subtitle: A novel of Virginia Woolf

- Book 2 Biblio: Hachette Australia, $29.99 pb, 261 pp, 9780349005652

This format is a risk, inviting comparison, as it does, between Parmar’s efforts and the lively and often brilliant voices of her subjects’ own diaries and correspondence. In the light of the originals, Parmar’s invented versions seem clunky and contrived. Not only that, but her Vanessa is inexplicably dour and resentful, and too often a mere mouthpiece for the insights of distinguished biographers such as Hermione Lee and Jane Dunn.

Certainly, Parmar’s narrative does not begin to convey the complexities of the relationship between Vanessa and Virginia as revealed in their own letters and memoirs. Yes, there was jealousy and competitiveness between the siblings, but these qualities were interwoven with an almost reflexive trust and understanding, and relieved by their inexhaustible delight in one another. Parmar brings out only the jealousy: as a result, her treatment of Virginia’s well-documented flirtation with Vanessa’s husband, Clive Bell, a major focus of her text, completely misses its significance. For the real-life Vanessa, this marital cataclysm led to a transformation in her attitudes to fidelity and individual freedom. It is a paradigm instance, in fact, of Bloomsbury’s commitment to shining the light of reason into the dark places of instinct, emotion, and social convention. For Parmar’s purse-lipped Vanessa, however, it is simply a case of bad behaviour on the part of her sister and her own ‘pig’ of a husband, which releases her from any further obligation to either. Such an approach misrepresents and diminishes the real people behind Parmar’s fictionalisations.

Norah Vincent’s Adeline is a work of an entirely different calibre. In her first pages, and in the third person, she effortlessly conjures the sense of interiority that Parmar struggles to create. It is 1925 and Woolf, in her early forties, is lying in the bath making up – as her diaries record she liked to do – her new book, To the Lighthouse (1927). Images, memories, and ideas bubble up in her brain and begin to coalesce into her most autobiographical novel. Vincent does not stop here, however, moving on to explore in separate ‘acts’ the historical moments around the composition of The Waves (1931), The Years (1937), and Three Guineas (1938), and ending with a recreation of the last days of Woolf’s life. She is particularly good on The Waves, which she links with the ‘mystical philosophy’ of W.B. Yeats, a benign, even avuncular figure in her text, who writes a poem for Woolf (‘Spilt Milk’). One of the strengths of the novel is the way it traces the threads of characters, ideas, and even phrases from one writer to another in Woolf’s circle, seeing, for example, Eliot’s ‘trilling wire in the blood’ in Woolf’s The Waves, and Woolf herself in Joyce’s Finnegans Wake.

Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell (Harvard University Library via Wikimedia Commons)

Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell (Harvard University Library via Wikimedia Commons)

Vincent’s evocations of Virginia and Leonard Woolf and their friends, including Lytton Strachey, Tom and Vivien Eliot, and Vita Sackville-West, are full of life, and do justice to their lively, humorous minds and complex emotional entanglements. The scene in which Leonard sits across the fire from Virginia reading the last pages of the manuscript of The Years while she waits anxiously for his judgement is particularly powerful. He does not love the work, but he knows that Virginia’s mental health is fragile just now – as always at the end of a big creative effort – and that a negative word from him could tip her into despair. Much as he wants to save her from a plunge into life-threatening depression, he is loath to violate the foundation of trust on which their relationship is built, their mutual commitment to honesty. Leonard’s quandary is beautifully evoked, and plays out most movingly.

Not all of the dramatic scenes work so well. I felt uneasy about one of the narrative’s central conceits, the existence of an alternative identity for Virginia in the form of her twelve-year-old self, Adeline, frozen in time by the trauma of her mother’s death. As far as I know, there is no evidence that Woolf suffered from dissociative identity disorder (what used to be known as multiple personality disorder), as Vincent seems to propose. Nevertheless, it is an effective narrative device, enabling Vincent to use dialogues between Virginia and ‘Adeline’ to explore Woolf’s past and its relationship to her fiction.

Some readers may find Vincent’s book too dense, particularly those who are unfamiliar with Woolf’s novels. But given her serious intentions, fine prose and profound engagement with her subject, this is a minor flaw. Adeline is cause for hope that in the rising tide of Bloomsbury novels one or two will emerge which genuinely draw us into that vanished world.

Comments powered by CComment