- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Sheila Fitzpatrick reviews 'Bloodhound' by Ramona Koval

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

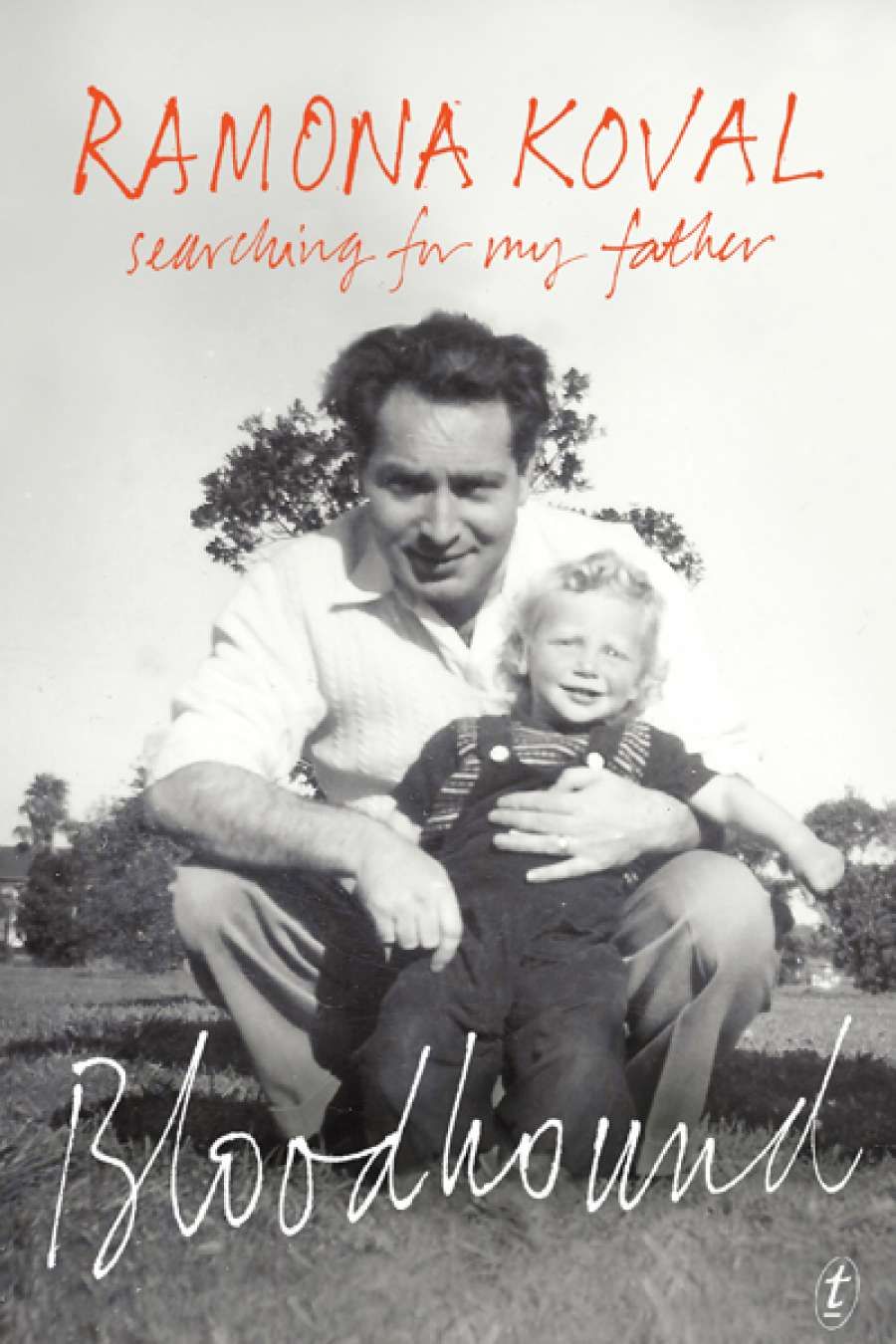

- Book 1 Title: Bloodhound

- Book 1 Subtitle: Searching For My Father

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 275 pp, 9781922182760

The book opens with a devastating picture of Dad at his eightieth birthday, a loud-mouth who has to be the centre of attention. Looking in his heyday like ‘a cross between a Mafiosi henchman and a plump Roy Orbison’, he seemed to have little in common with his elegant, book-reading wife. It was one of those DP marriages made almost at random in the aftermath of catastrophe, so as not to be totally alone. There was no warmth between them, and Koval says repeatedly that Dad never cared for her, either. Details of her narrative do not entirely support this, and she admits that her birth after nine years of failure to conceive was a miraculous moment for him. As he is dying, she distances herself even further, physically and emotionally, leaving other relatives to carry the burden. This is reported with some but not a lot of self-reproach.

It seems plausible that her attractive, sexy mother might have had affairs, but if it was a lover who fathered her daughter(s), she was not inclined to reveal this, then or later. A woman of secrets, as perhaps most DPs were, she had left her home at fourteen to avoid being discovered as a Jew by the German occupiers, and spent two and a half years alone in Warsaw under an assumed name during the war, her plaited hair pinned to the top of her head like a good Polish Catholic girl.

‘With her dark curly hair and broad shoulders, Koval didn’t look like any of her close family’

Not for nothing does Koval call herself a bloodhound in her efforts to prove that someone else was her father. She finds two candidates: one the owner of the textile factory in which her mother worked before her birth, the other a married family friend. Both candidates, like Dad, were also DPs from Poland, one a Holocaust survivor with an Auschwitz number on his arm, the other a Jew who escaped by fleeing or being deported to the Soviet Union. It is not long before blood tests establish that Koval and her sister are in fact only half-siblings. This means that one of them, or possibly both, were not Dad’s biological children. Her sister, who regards Dad as her father, wishes Koval had never started the hunt, but Koval presses on regardless of collateral damage.

The author is aware that her obsessive quest verges on the ridiculous, and the note of irony and self-mockery is part of the book’s appeal. But that doesn’t mean she is not aggrieved – with Dad in the first place, for failing to care for her as a father should, but also with the lovers/putative fathers who did the same. Towards the end the book begins to wander, from German classes at the Goethe Institute in Berlin to the history of the Khazars, long-ago Jewish converts to whom Koval sees a physical resemblance.

Her quest, which lasts more than a decade, veers off in a new direction. An article on climate change claims that by 2050 Poland will be tropical and Australia too hot and dry. This gives her the idea that for her grandchildren’s sake they should all get Polish citizenship. This is reported ironically, but in fact Koval is serious. Citizenship is available upon application if your parents were pre-war Polish citizens, and after the predictable bureaucratic hassles she finally succeeds. Dad, incidentally, hated Poland; he once told Koval that for him it was just ‘a Jewish huge cemetery’.

Skip the book’s lame ending and turn back to the slyly subversive epigraphs at the beginning: two warnings about asking too many questions and, above all, Carlos Fuentes’s suggestion that the dead have the right to carry their secrets to the grave. Do they? This memoir leaves you wondering.

Comments powered by CComment