- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Picture Books

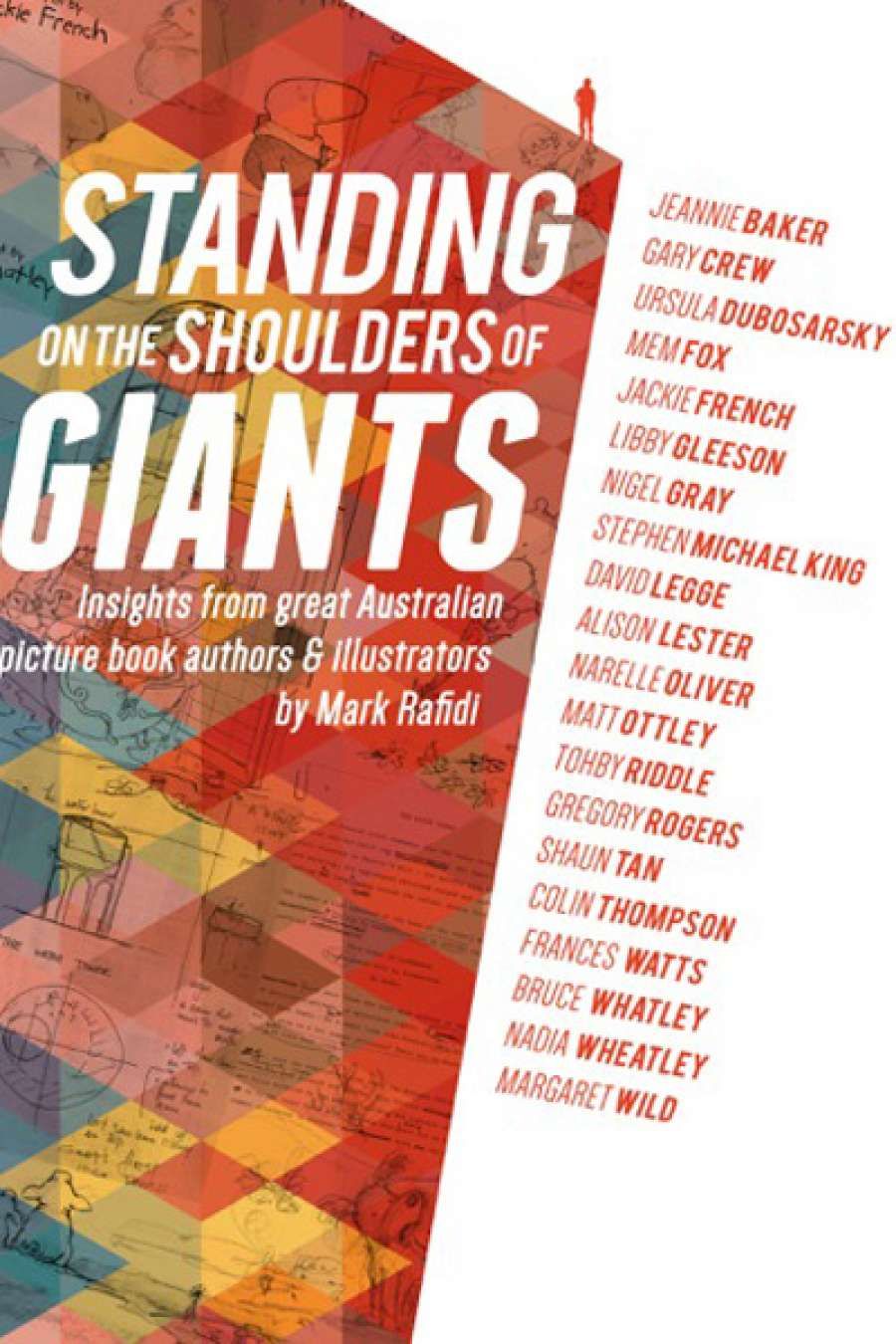

- Custom Article Title: Ruth Starke reviews 'Standing on the Shoulders of Giants' by Mark Rafidi

- Book 1 Title: Standing on the Shoulders of GIants: Insights from Great Australian Picture Book Authors and Illustrators

- Book 1 Biblio: Harbour Book Publishing House, $39.95 pb, 248 pb, 9781922134257

In the first part of the book, ‘Biographical Musings’, Radifi asks each writer and illustrator the sort of basic questions you might hear at any writers’ festival. We learn that most writers and illustrators are up with the birds, brewing coffee, reading newspapers, and going for walks or visiting the gym before settling in for a day’s work. There are always interruptions, email being the biggest, and for those who work from home – and that’s almost everyone – domestic duties and childcare, although only Jackie French gets interrupted by wombats bashing at the door. The prolific French accomplishes more before breakfast than most writers do in an entire morning, and by the end of the day she’s made soup, a casserole, a cake, and a vat of grapefruit marmalade – and probably written another three books. As she explains, ‘I think quickly. I write quickly – so quickly and in such amounts it is often embarrassing.’ She is also dyslexic, something Rafidi describes as ‘one of the less [sic] known things’ about French.

In the same vein, ‘one of the things that is less widely known’ about Stephen Michael King is that he suffered hearing loss as a child; ‘one of the things that isn’t as well-known’ about illustrator Gregory Rogers is that ‘he is also a musician’. Greg Rogers is also dead. He died of cancer in May 2013, but nowhere in the interview is this mentioned. Neither is the fact that he was the first Australian to win the prestigious Kate Greenaway Medal for book illustration, (in 1994 for Way Home, written by Libby Hathorn), which is surely of more interest and relevance to readers of this book than his musical tastes.

‘The prolific French accomplishes more before breakfast than most writers do in an entire morning, and by the end of the day she’s made soup, a casserole, a cake, and a vat of grapefruit marmalade’

In the second part of the book, the subjects respond to ‘The Top Ten’ questions about the creative process, including some curly ones like ‘What makes good literature?’ Colin Thompson has the answer: ‘Something that is not pretentious ... That’s why I’ve never finished any Booker Prize winner.’ Asked about the relationship between the written text and illustrations, he seems to think that there isn’t one: ‘Writing demands a lot more imagination on the part of the reader. With illustrations it’s all there in front of you.’ He can write a picture book ‘in as little as a day sometimes’ and he thinks kids ‘get bored with bloody teddy bears and cute crap’. Rather unfortunately, Thompson’s interview is followed by one with writer–illustrator Frances Watts, whose characters are always animals and who has a protagonist called Parsley Rabbit.

Writer–illustrator Matt Ottley is colour-blind (a little-known fact), and his book Requiem for a Beast (2008), which uses words, illustrations, and music to tell a multi-layered allegory about a young stockman chasing a feral bull, has the distinction of being the ‘most complained about book in the history of Australian publishing for children and young adults’. The reason, says Ottley, is because ‘it doesn’t do a Banjo Paterson or Henry Lawson’. Teachers and parents complained that it was inappropriate material for young readers. Frustratingly, there are no illustrations from this book and, even more frustratingly, those of Ottley’s that are included are uncaptioned. Sometimes, as with the sketches for Narelle Oliver’s Fox and Fine Feathers (2009), it is self-evident which book they refer to, and sometimes, as with Stephen Michael King’s sketches for Mutt Dog (2005), the artist himself has scrawled a title, but in far too many cases the reader has to guess to which book uncaptioned sketches and work-in-progress belong.

‘He can write a picture book ‘in as little as a day sometimes’ and he thinks kids ‘get bored with bloody teddy bears and cute crap’’

This was only one of the irritations of this book, and I lay no blame on the contributors. They are not responsible for the typos, the repetitions, the sentence fragments, or the peculiar punctuation, of which this is typical: ‘David’s life began in England, he shares some memories about his time there, “I lived the first twenty five years of my life in England, so I have many vivid memories.”’ There are contradictions: Nigel Gray tells us he was born in the north of Ireland, and on the very next page Rafidi writes ‘Nigel was born in England.’ There is no bibliography or list of the contributors’ books. No information is given about when, where, and how the interviews were conducted. Rafidi, who teaches English at a private Anglican school, writes clunky, inelegant, and sometimes nonsensical prose. ‘Picture books have a unique relationship not found in other literary texts,’ he tells us; ‘Typical of Oliver’s works, she discusses camouflage ... ’ I felt myself sinking into the sort of despair I often succumbed to when marking undergraduate English essays, when, over and over, I would find myself scribbling with a red pen in the margins the phrases Learn how to introduce a quote! and Rethink this sentence!

Comments powered by CComment