- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Crusader Hillis reviews 'The Boatman' by John Burbidge

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

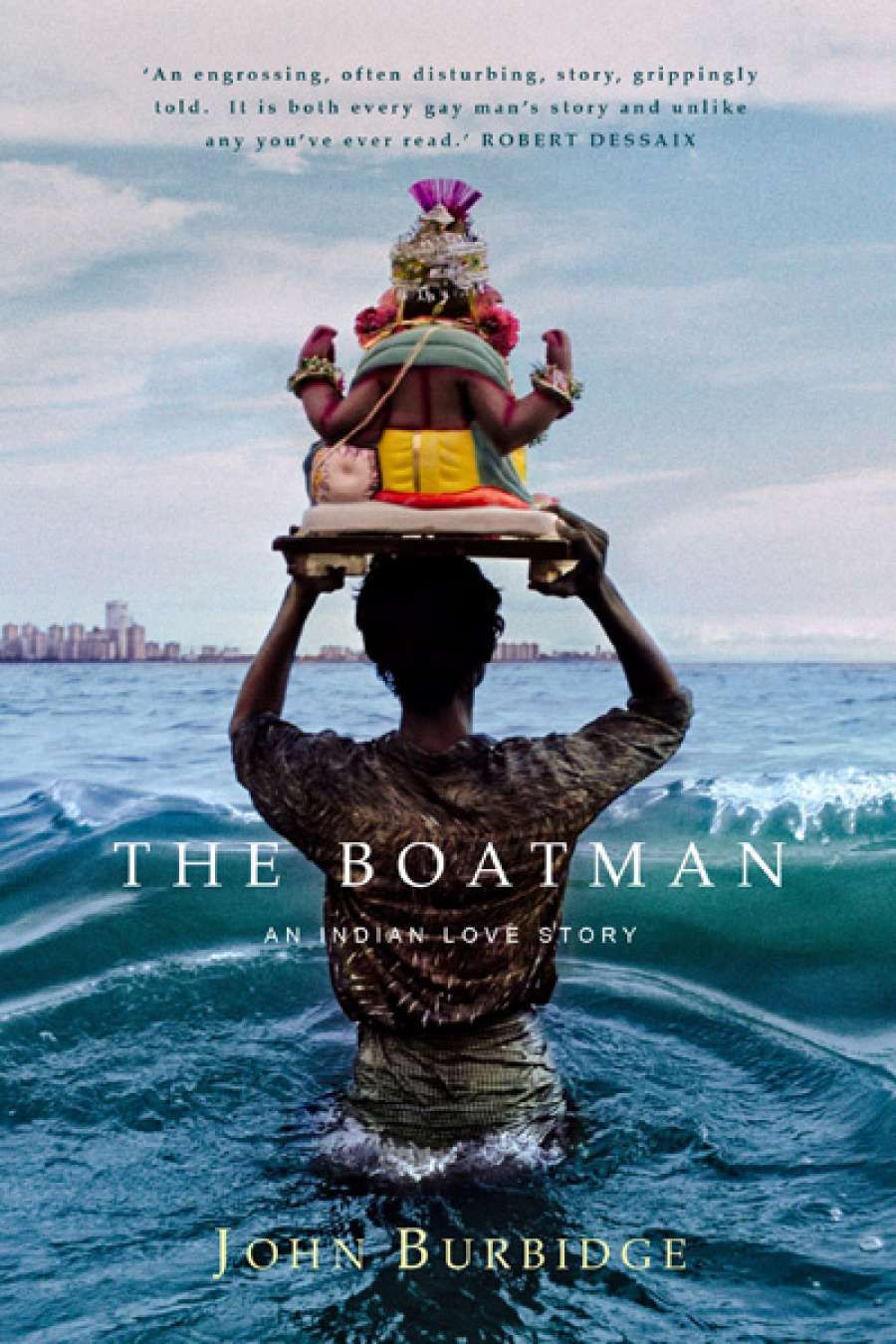

- Book 1 Title: The Boatman: An Indian Love Story

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $29.99 pb, 270 pp, 9781921924804

In 2007 the Indian Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional the 1861 British-imposed law against sodomy, but a subsequent review by largely religious judges overturned the decision meaning that gay men, lesbians, transgender, and third-sex individuals again face prosecution and continue to be ostracised or worse by their families, colleagues, and friends. The ruling, which came just weeks before Burbidge’s launch in New Delhi, holds that because LGBT Indians make up such a miniscule proportion of the population their constitutional rights are not impacted. It was suggested in the Indian media that Burbidge’s sexual history (encounters with 200–300 men in the space of two or three years in the early 1980s) undermined this assertion.

Burbidge arrived in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1980 as a communications and fundraising worker for an international community development organisation that was based on Ghandian principles. Work happened in a grassroots, low-cost fashion with the aim of direct local impact. His first couple of years were spent in Indian villages, where he lived on a pittance, and usually slept on mats, living, eating, and working with the locals. After some time he was transferred to Bombay, where he lived in such close quarters that he describes the experience as akin to being in a religious order.

John Burbidge had grown up in an upright Christian Perth family. His decision to embrace a low-paying job in Indian villages was not on his parents’ list of vocations for their son. However, Burbidge thrived in India and quickly became a respected and valued member of his organisation. In 1982, at the age of thirty, he happened on an issue of Sexology Today. Scanning its contents, an article on homosexuality jumped out at him. Within weeks, Burbidge’s life had turned upside down.

‘In 1982, at the age of thirty, he happened on an issue of Sexology Today. Scanning its contents, an article on homosexuality jumped out at him. Within weeks, Burbidge’s life had turned upside down.’

What follows is a description of his rapid immersion in the public gay sex scene of Bombay’s streets and parks. His first experience with a beach masseur was followed shortly thereafter by sexual encounters in public places in Bombay, as well as in Calcutta and Delhi, where his work often took him. The book at this point describes a series of risky encounters in the pursuit of sex with young Indian men that are so numerous and similar that they might have been relayed in many fewer pages while making the same point. They are also described in an often coy or generalised fashion – presumably for the benefit of an Indian readership – which makes their retelling less than riveting.

Unlike other foreigners in India, Burbidge’s lack of funds made it impossible for him to move among middle- and upper-class gay men, where sex might be enjoyed more privately or lead to an ongoing relationship. Over time, however, he developed a wide-ranging network of gay men, many of them students, and opportunities for sex in rooms became more numerous. Burbidge seemed to relish the dangers; numerous encounters with violence and interactions with corrupt police – which could have resulted in severe beatings, blackmail, or imprisonment – did nothing to impede him. He makes oblique references to numerous bouts of sexually transmitted diseases and to the fear of Aids, but no further detail of these travails is provided.

At the same time that Burbidge was realising his sexual fantasies, he was deeply involved in his community development work, which took him into contact with every echelon of Indian society. One day he might be in his cramped dormitory room, on another soaking up the lavish hospitality of the rich Indians who supported his organisation.

‘One day he might be in his cramped dormitory room, on another soaking up the lavish hospitality of the rich Indians who supported his organisation’

The memoir has dark undertones of the price of his double life, including the increasing attention he received from his colleagues who were aware of his nocturnal adventures. At various points in the book, Burbidge reflects on whether his behaviour was a form of addiction; the risks he took to find sexual release could be read as such. Yet, it could just as easily be read as a thirty-year-old man finding himself in the flush of adolescent sexual awakening, with all the daring that might entail.

The title of the memoir, ‘The Boatman’, is a play on the word ‘cruising’, a term meaning trawling for gay sex, and is a nickname given to him by one of his few work confidantes. Its subtitle, ‘An Indian Love Story’, refers to Burbidge’s love of India and its people. His love cannot be doubted, and his observations of Indian life are fondly related and filled with sentences and phrasing that summon the sights, smells, and sensibilities of India in the 1980s. He is also highly sensitive to the mores and customs that many visitors overlook. However, thirty years after the events it describes, there is a surprising lack of reflection in the memoir and, at its weakest, parts read more like a series of events closely detailed than a fully reflected account of his life during such formative years. I enjoyed this book, and it tells an important and often moving story, but greater specificity of detail and a more nuanced account of his experiences would have strengthened it as a memoir.

Comments powered by CComment