- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Toby Fitch reviews 'Drones and Phantoms' by Jennifer Maiden

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

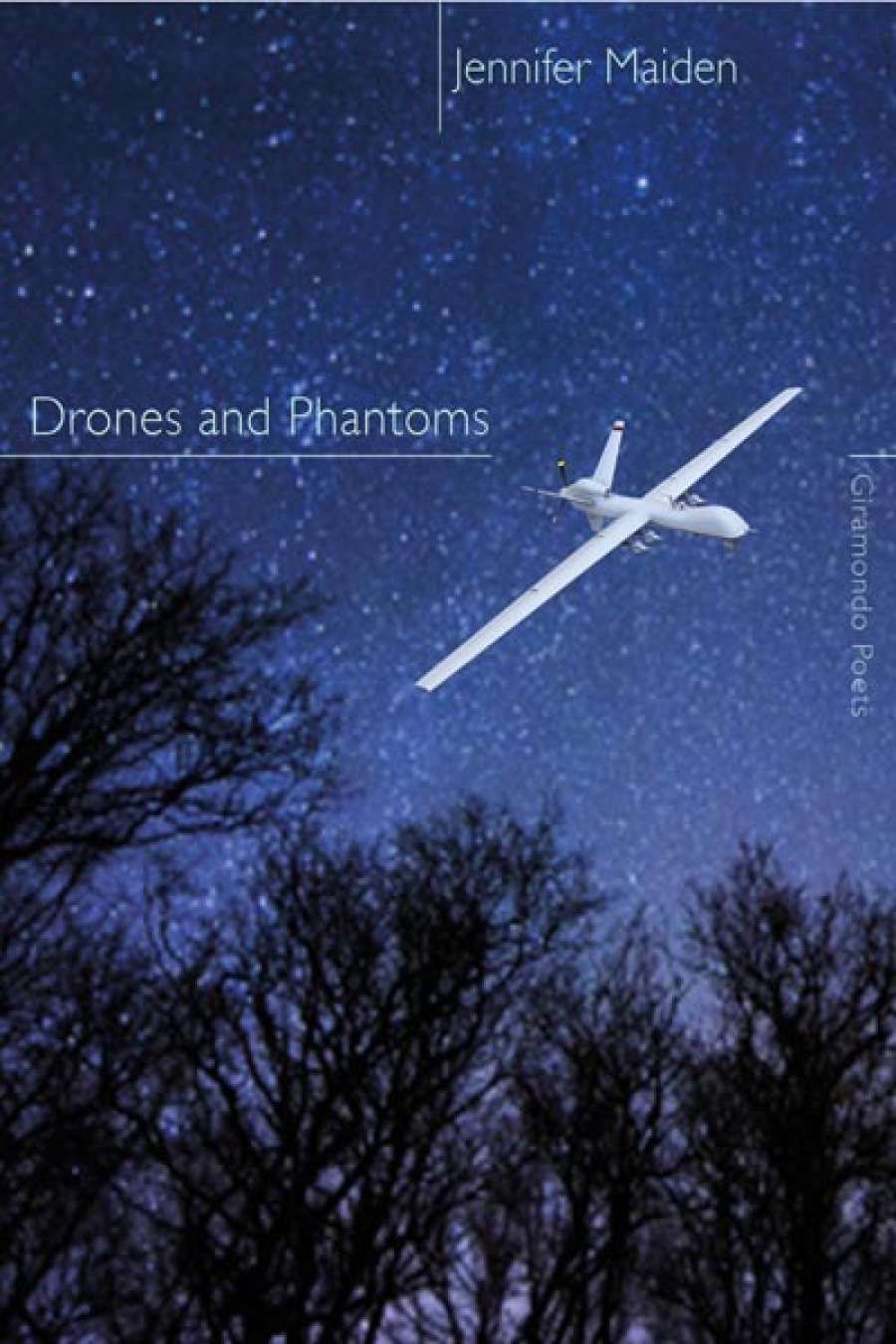

- Book 1 Title: Drones and Phantoms

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 80 pp, 9781922146724

Drones and Phantoms has structural, not just modal, parallels with her recent books, such as the interspersing of shorter, more classical, lyric poems. The second-last poem, ‘My Heart Has a Deep Water Harbour’, reprises the penultimate one in Liquid Nitrogen (2012), ‘My Heart Has an Embassy’. The lyric poems in Drones and Phantoms have become more formal in their use of rhyme (‘Map in the Mind’), and repetition (‘I’ve done this wrongly before’, ‘Digging for Hoffa’, ‘My Heart Has an Embassy’). Most poems, including the discursive, tend to be bookended: the first line, idea or salvo, returns to wrap up the poem, though usually with a heightened lyric flavour. It is almost predictable, and oddly recalls the intros (that set the tone) and outros (that augment and embellish the tone) of nightly news programs. In this sense, Maiden’s bookended structures (or should we call them reels?) – refracting a media-saturated world through Maiden’s imaginative world – are fitting and somehow comforting.

‘Maiden exploits the discursive, lyrical, essayistic, philosophical, political narrative mode that she has come to be recognised for, garnering major Australian literary awards’

Yet within these reels the reader does reel – from each vibratory association to the next. One of Maiden’s primary objectives is to confront the reader’s conventional expectations of his or her own ethics. In ‘The Day of Atonement’, she aligns her sense of self and work not with Gillard’s tone of ‘ethical security’, but with Kevin Rudd and Tony Abbott, ‘whose / eyes glow … born unsure’, and who ‘survive / complicit with the dark.’

While uncomfortable, Maiden’s mode is also a ‘relaxed comic mode’, as Martin Duwell once wrote, in which she ventriloquises living and dead historical figures and politicians, pairing them off in conversations so as to present opposing attitudes and anxieties. In this way Maiden can play devil’s advocate and empathiser, and tease out the complexities and ethical ambiguities of world events in private, fanciful reckonings. Returning in Drones and Phantoms are the pairs Hillary Clinton and Eleanor Roosevelt, Kevin Rudd and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Julia Gillard and Nye Bevan, Mother Teresa and Lady Diana, plus Maiden’s fictional avatars George Jeffries and Clare Collins. Her cast widens to ventriloquise Barack Obama and Nelson Mandela, Tanya Plibersek and Jane Austen, Queen Victoria and a pre-prime minister Tony Abbott, who offers this prophetic gem: ‘But Ma’am, inside me everything is war.’

‘In ‘The Day of Atonement’, she aligns her sense of self and work not with Gillard’s tone of ‘ethical security’, but with Kevin Rudd and Tony Abbott’

These poems and Maiden’s poems in the first person, in which she frequently banters with her daughter, Katharine, explore a vast array of topical issues (the Cypriot financial crisis, Ethiopia, assassination, refugees on Manus Island, Eyjafjallajökull, ASIO, the dismemberment of Marius the giraffe) and abstract ideas (cosiness, complicity, silence, economy, grey matter, ‘cloud-code’). She also writes about poetry more than ever. Poets, reviewers, editors, and publishers are mentioned or inferred for whatever issue at hand. Sappho, Sylvia Plath, Frank O’Hara, Emily Dickinson, Judith Wright, the Marquis de Sade – all feature. Sometimes her concern with how her books are received by reviewers is obsessive,but for the most part is all in good fun, adding another layer to the usually formal dialogue of the literary sphere. Maiden is refreshingly open about her convictions regarding poetry and politics (‘Not cut up, / the politics is still poetry’) and how contradictory that can seem:

Poetry

making always involves the fear

that what whistles in from the ether

has been given to someone other

simultaneously …

For Maiden, poetry is digital technology, conceptually and metaphorically, because it presents ‘disparate concepts in binary structures’, while prose, flowing and continuous, is analogue (from Liquid Nitrogen). A poem cannot be reduced to a single trope because there is an other, a phantom, a multiplicity. Intertwining binaries throughout her interrogative narratives (pairs of characters, opposites such as light and dark, spondaic and trochaic rhythm, and word-sound associations like ‘ether’ and ‘other’), Maiden explores how truths are, ultimately, multi-faced and illusive. Freely associative, her poems become double helices – sinuous streams of (cloud-)code twisting down the page (‘Streams, thought George, crouching in one, are sinuous’). Building serially on her many tropes, the poems increasingly display a genetic code that concatenates across her oeuvre. It is all very self-aware and clever.

Less constrained by their own cleverness, the George and Clare poems return for the fourth consecutive book with narratives more hallucinogenic than any previously, air swirling ‘like aerated wine’. Of all Maiden’s serials, the George and Clare poems are the most versatile and multiple because the characters are fictional first, and real second, allowing greater freedom of emotion and narrative possibility. There is also a lightness of touch, a whimsy, unmatched in her other poems, and in most other poets in Australia, that empowers Maiden (and her two avatars) to go where few would dare, ethically and imaginatively. In ‘Clare and Manus’, Clare and George find themselves in a tropical hallucination above trees on Manus Island, ‘uncertain / whether it would be the police / or camp guards who killed them, / and whether by guns or machete’. Contemplating prison, police Black Talons, Oscar Pistorius, the recent beatings and death on Manus Island, and substituting the anger felt over the killing of a lion family in Copenhagen, they plot their violent escape from the Patrol on the ground below. Clare ends up torching a truck: ‘The Manus boatman / as they sailed quietly off was quietly pleased / by the unexplained small dawn on the horizon.’

George and Clare are characters transposed from Maiden’s novel Play with Knives (1990) and from what she herself has described as its ‘notoriously unpublished’ sequel Complicity, or The Blood Judge. As old imaginary friends, they carry with them an air of latency that Maiden can increasingly draw upon at will. Arthur Rimbaud wrote nearly 150 years ago that ‘genius is the recovery of childhood at will’. George and Clare could well be viewed as an intertwining binary representation of Maiden’s subconscious, or as the two faces of a Janus-like avatar, or as a childish whim. However one looks at them, they are surely recovered traces of genius.

Comments powered by CComment