- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Michael Morley reviews 'Naked Cinema' by Sally Potter

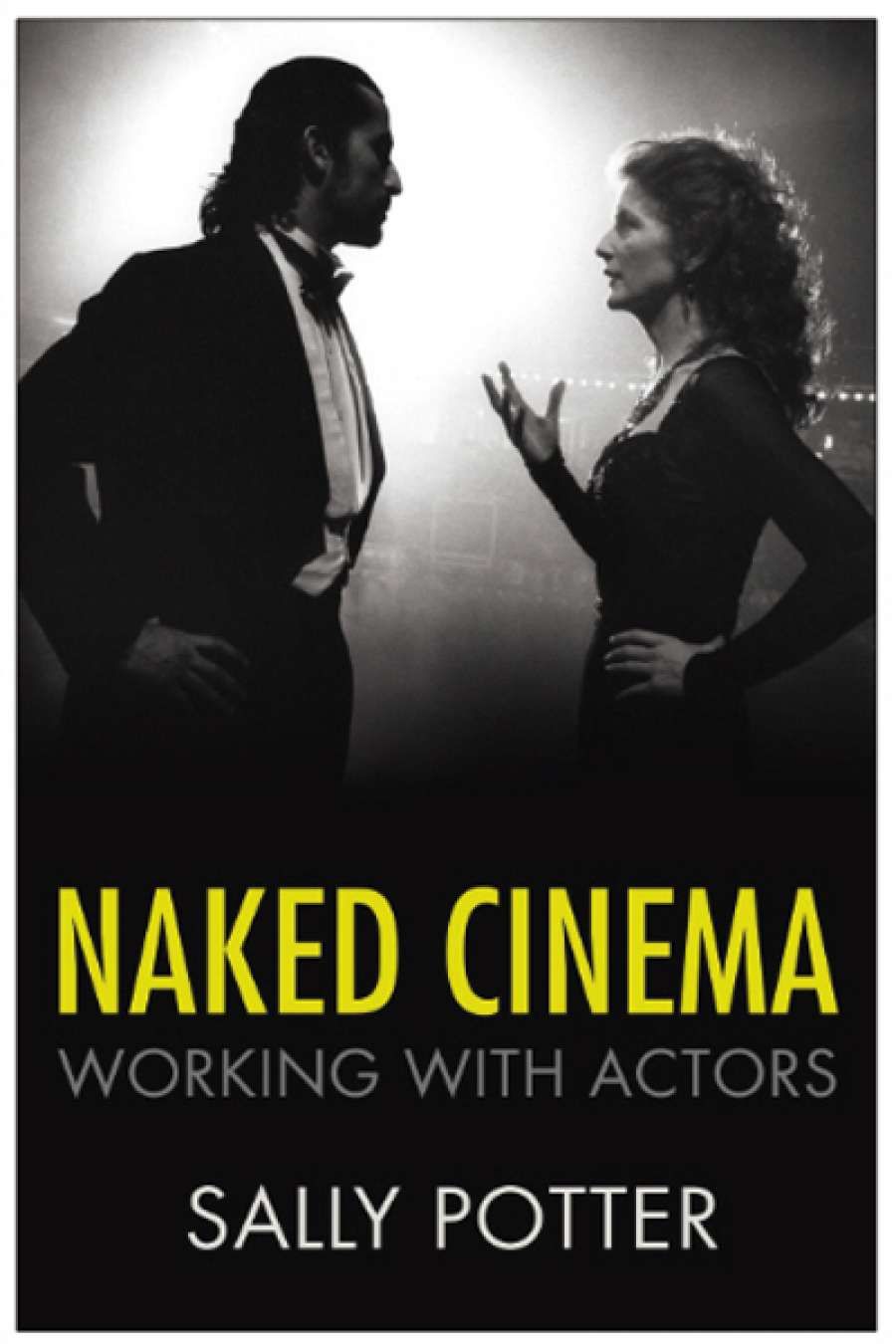

- Book 1 Title: Naked Cinema: Working With Actors

- Book 1 Biblio: Faber & Faber, $39.99 pb, 438 pp, 9780571304998

The interviews make up almost two thirds of the book, and represent both a valuable resource and a series of insights, mostly revealing and illuminating, dotted with comments that range from the unhelpful to the banal, along with, it has to be said, some theatrical luvvie-speak that might have benefited from a tough editor. I suspect that I might not be the only reader to be both baffled and unenlightened by many of the observations of Riz Ahmed (so impressive, incidentally, in Four Lions, 2010). When, in response to Potter’s question about what he might need from the director in rehearsal and in the shoot, Ahmed notes: ‘I suppose the ideal mixture is someone who’s got your back on a checking kind of level’, one wonders what benefit either students or professionals might derive from such a mantra – especially when it is linked with blanket rules such as ‘Inside-out feedback helps. Outside-in feedback hinders.’

But such missteps are easily and productively offset by the comments, personal and professional asides, and insights proffered by, among others, Julie Christie, Steve Buscemi, and Joan Allen, together with Potter’s own glosses, more detailed commentary, and informally pitched instructions. Under Preparation, for example, she balances crisply couched summaries of auditions (what really happens), with clear and cogent statements on improvisation (finding freedom?)

Potter’s added question mark is deliberate, and her explanation spells out what is, for her, one of the many things that differentiate film from theatre:

Most film actors, however, will find improvisation exercises of the kind often used in theatrical rehearsals both embarrassing and unnecessary. Games, ball-throwing and other types of group work often used to build a sense of ensemble in a stage production can be counter-productive when preparing for a film. This is because the actor’s energy needs to be focussed in a different, more individual way for the lens.

This note is struck again by several of the actors interviewed. Julie Christie, responding to the question of whether the camera can follow or read thought, believes that the camera ‘can create thought’, going on to note that ‘ you can have something which is ugly and boring in a close-up and loses the magic it needed that it would have had in a wide shot’, before revealing, with engaging artlessness, that she is so unaware of the camera that she’s ‘actually quite skill-less’, and is always being told ‘the camera’s here, Julie, not there’.

‘I suspect that I might not be the only reader to be both baffled and unenlightened by many of the observations of Riz Ahmed (so impressive, incidentally, in Four Lions, 2010)’

While Christie and most of the other interviewees might be unconcerned about details such as different lens sizes, there are strongly divergent views on such questions as directors who devote their attention (and gaze) to the monitor, rather than the actor. Buscemi, for instance, has a ‘really hard time with people in my eye-line’, while being ‘so used to directors looking at their monitors that I don’t really think about it’.

Compare that, for example with Annette Bening’s insistence that having the director’s gaze truly on you ‘makes a huge difference’, and insisting that ‘it’s opposite to the fucking video monitor where everybody’s gone in the other room’. Or Jude Law, who, with perhaps characteristically British pragmatism, notes that the director/monitor question ‘has transformed in the last ten, fifteen years … I’ve had directors who don’t operate [the camera] … but they sit next to the camera. And I’ve had those who are off in a blackened tent and then pop out or you get beckoned over.’

If there is one unifying feature to the responses elicited by Potter’s questions to her subjects, it is that issues such as rehearsal/winging it, script/director, external/internal, instinct/intuition, imagination/visualisation have articulate advocates on both sides of the (only seemingly) dividing line. Or, as TLS’s Michael Caines (not to be confused with the actor) neatly puts it in a recent account of a father and son approaching the task of creating a character (in this case, Timothy West playing Falstaff to son Sam’s Prince Hal): ‘On comparing scripts … in rehearsal [he found that] his son has written reams of self-interrogation, psychologically inflected instructions to himself, while he has merely written: “move boot”.’

Quot actores, tot sententiae.

Comments powered by CComment