- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Bernadette Brennan reviews 'One Life' by Kate Grenville

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

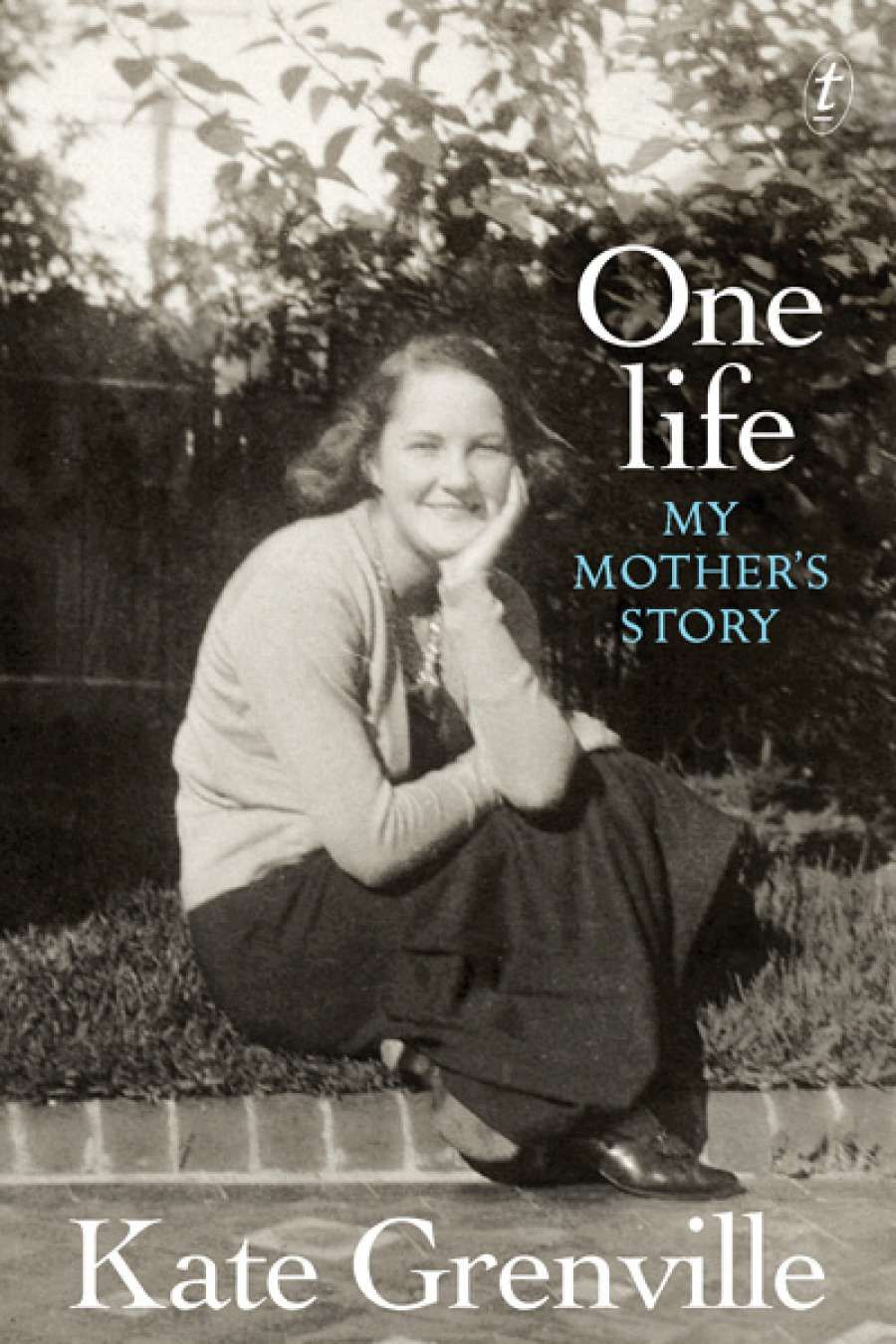

- Book 1 Title: One Life: My Mother's Story

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 hb, 260 pp, 9781922182050

A number of Australian women writers have penned memoirs about their deceased mothers: Gabrielle Carey, Anne Summers, Drusilla Modjeska, Kristina Olsson, and Maggie MacKellar to name a few. In Poppy (1990), Modjeska acknowledged that she fictionalised her mother’s diaries, thereby delighting some critics and outraging others. Twenty-five years on, Grenville writes in the third person, entirely through Nance’s imagined consciousness. The prose is flat, unadorned, and occasionally irritating: ‘She thought, thewonderful thing about hard times is that you don’t need a Caribbean cruise. It’s enough to have the day to yourself.’ And elsewhere: ‘your children are just on loan to you, she thought … That will be my last gift to them, she thought: to let them go.’ To be fair, Grenville explains her method, but not until the final sentence of the postscript: ‘this book is my attempt to continue what our mother wanted to achieve with those fragments of memoir: to tell her story and put it in its context of time and place. I hope it might be something like the book she might have written.’ For that project of love, Grenville cannot be faulted. Her approach is risky, and the memoir consequently lacks the energy it might otherwise have had, but ultimately Nance’s story develops a momentum of its own.

Good memoirs narrate some aspect of a life that goes beyond one individual’s experience to resonate deeply with broader, more universal issues. At the outset of One Life, Grenville acknowledges that Nance’s ‘story is unusual in some ways, but in other ways it’s the archetypal twentieth-century story of the coming of a new world of choices and self-determination’. Therein lies the double worth of this memoir. Grenville quite deliberately narrates Nance’s life in considerable – often prosaic – detail, but the obstacles Nance faces in gaining an education, in slaving away at her hated profession of pharmacy during times of great need, in desiring men, using contraception, setting up businesses, juggling work and motherhood, and being powerless to leave a troubled marriage, speak to the lives of countless twentieth-century women. As One Life attests, understanding the joys and hardships of women’s domestic life matters.

Nance (left) with her assistant in the Balgowlah pharmacy, 1954

Nance (left) with her assistant in the Balgowlah pharmacy, 1954

Grenville’s readers will enjoy the early mapping of Nance’s family tree. Solomon Wiseman and his daughter Sarah make a cameo appearance (as does Bea Miles later in the narrative). Nance’s mother, Dolly, born in 1881, is Sarah’s granddaughter. Dolly marries Albert Russell, and Nance is their second child. In the postscript, Grenville tells us that ‘Dolly and Bert were as strange to me as if they were from another planet. They made my mother strange to me too. This scary old woman and this big rough old man were her mother and father, but there was no way to put my Latin-using, poetry-quoting mother together with these old people with their foreign ways.’ Through the first half of the memoir, however, Grenville as author unravels that strangeness. We come to understand and feel deeply for Nance, largely an abandoned, clever child who suffers repeated dislocation and loss.

Nance survives the Depression years slogging away as an apprentice pharmacist in Sydney. All she wants to do is teach, but teacher training does not come with a wage. She has a few romances, rebuffs two marriage proposals and eventually meets an educated, charming man who seemed to be ‘on the inside of the mysterious business of politics, living in a bigger world than she ever had a chance to know’. Kenneth Gee, then a Christian Socialist and from a social class well above Nance, admires and esteems her. Sadly, Grenville suggests, he was incapable of love. They marry. Ken becomes a Trotskyite and their world is peppered for a short while with people like John Kerr and Jim McClelland. Ken may have come from a more sophisticated world, but he lives a fairly mundane life as a suburban solicitor, failed barrister, and eventually crown prosecutor. The marriage fails after twenty-five years when one of Ken’s many affairs results in a pregnancy. Interestingly, Ken does publish some stories and three books.

‘During World War II the family moves to Mona Vale where Nance enjoys the company of ‘pinkos and artists’’

Nance, on the other hand, continues to work when married, pregnant, and a mother of young sons. During World War II the family moves to Mona Vale where Nance enjoys the company of ‘pinkos and artists’. At the war’s end, she returns to work for a pharmacist, sends her sons to ‘an outrageous sort of school’, and decides to set up her own pharmacy. This gutsy woman overcomes the many hurdles placed in her way. The pharmacy is a great success, but within months she has to sell it because there is no childcare. Not to be deterred, she settles back into ‘home duties’; only Nance’s home duties involve bricklaying and building her own house.

The memoir proper ends when Nance knows she is pregnant with her third child, the child who will be Kate Grenville. In the postscript we hear that Nance went on to buy – and have to sell for the same reason – another pharmacy, completed an honours Arts degree, and became a teacher. Grenville notes that the ‘memoir-fragments she left are mostly matter-of-fact’, and that the irregular diary entries are ‘full of pungent observations about the people around her’. We are not given any of this original material, though we are privileged to read the letter Nance wrote to her children and attached to her will.

Nance ‘often quoted Socrates’ famous maxim: The unexamined life is not worth living’. In One Life, Grenville examines and celebrates Nance’s life. The memoir is Grenville’s gift to her mother. It is also a gift to countless readers who will recognise their own experience, or their mother’s experience, in these pages.

Comments powered by CComment