- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Film

- Custom Article Title: Philippa Hawker reviews 'John Wayne' by Scott Eyman

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

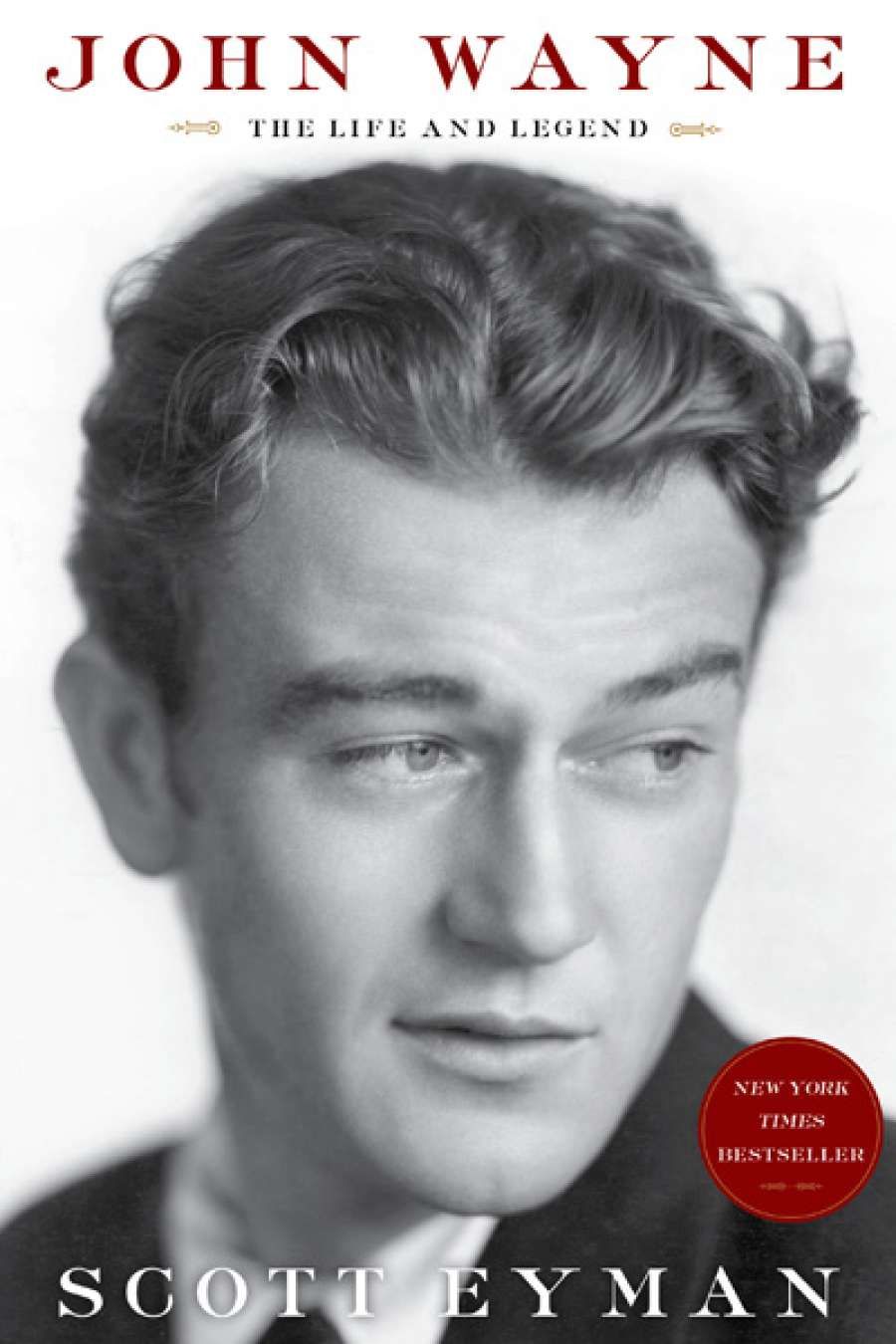

- Book 1 Title: John Wayne: The Life and Legend

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $39.99 hb, 657 pp, 9781439199589

Wayne was born Marion Morrison in 1907 in Winterset, Iowa; his nickname, ‘Duke’, was borrowed from a family dog. He was a model student at high school, an academic achiever, and class president. He won a football scholarship to the University of Southern California, where he intended to study law. While he was at college, he found work in the movies at the Fox lot, even before he lost his football scholarship. Gradually, he began to think of a future in film. He was an extra for several years, beginning in the silent era, before his first break in Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail (1930), an ambitious widescreen western. He was given a new name, John Wayne, and a contract; when the film flopped he kept the name, but lost the contract. He spent the next few years in minor movies and serials, serving a protracted apprenticeship that Eyman explores in well-chosen detail. It wasn’t until 1939, with John Ford’s Stagecoach, that things fell into place for him.

Eyman met and interviewed Wayne in the 1970s. He has written studies of legendary Hollywood film-makers, including a biography of Ford called Print the Legend (1999), and he is well placed to portray this most crucial of figures in Wayne’s life. Theirs is not an easy relationship to understand, because it is bound up in a kind of sadistic exercise of power by the director, a harsh, controlling paternalism employed over decades. Ford gave Wayne his greatest roles – most of all, in that peerless, complex western, The Searchers (1956) – but often treated him with contempt. Wayne was devoted to Ford and devastated by his death.

On screen, Wayne was a hero of World War II; off screen, he did not serve in the armed forces, unlike many of his movie contemporaries. Eyman does his best to investigate the reasons behind this. It appears that Wayne made an effort to join the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), without pressing too hard. His absence from the war left Wayne defensive; more ready, perhaps, to take up the postwar political fight and become a Cold War warrior. Yet Eyman tends to minimise Wayne’s political activities during the blacklist era, to suggest that he was much more tolerant as a person than his political stance suggested, or some of his more controversial statements in interviews would imply. For those looking for a critique of Wayne as an ideological figure, John Wayne’s America: The Politics of Celebrity (1997), by Garry Wills, is the place to go.

John Wayne and Claire Trevor in Stagecoach (1939)

John Wayne and Claire Trevor in Stagecoach (1939)

John Wayne, according to Eyman, often surprised people when they met him for the first time. He was more good-natured and intelligent than they expected. He loved to play chess. He was not good with money, too ready to go into business with friends, too easy to take advantage of; ‘smart but not shrewd’ is how Maureen O’Hara describes him. He was driven to keep making movies because that was what he knew and loved, but also because he needed to pay his bills. Wayne was married three times and had seven children; Eyman suggests that he was a doting but frequently absent father, and that his relationships were limited by the fact that he was ‘an expansive man who was a little afraid of women’.

‘Ford gave Wayne his greatest roles – most of all, in that peerless, complex western, The Searchers (1956) – but often treated him with contempt’

The focus in the book, however, is on the movies he made. Eyman goes into considerable detail about budgets and box office, and into the operations of Wayne’s production company, Batjac Productions. He has some perceptive things to say about Wayne’s screen presence, his strengths as an actor, his awareness of his craft. Fellow actors, male and female, attest to his professionalism, warmth, and good nature, in affirmations that appear so regularly they almost feel like testimonials.

It all becomes a little melancholy towards the end: movie sets were the only places where Wayne felt at home, particularly after the failure of his third marriage. His choices became more restricted, partly because he had lost some of his currency, partly because he refused to consider certain types of roles. There is no reason to regret his lack of interest in a Blazing Saddles cameo, but there is at least one picture one wishes he had made. Eyman mentions a script called The Hostiles, written by Larry Cohen, a western about an uneasy alliance between a younger and older man that had been optioned by Clint Eastwood in 1973. He offered it to Wayne, thinking that they could both star in it. Wayne refused, more than once. Finally, Wayne threw the script into the ocean.

On his final film, The Shootist (1976), Wayne didn’t behave well towards the director, Don Siegel, often challenging him on set. He was in poor health and had to take a couple of weeks off; several scenes were shot using a double. In one of them, Wayne’s character shoots a man in the back. Wayne was shown rushes, and was horrified. ‘Wait a goddamn minute,’ he said. ‘I’ve never shot anybody in the back and I’m not going to start now.’ At that point, he and his screen persona were as one. He was very clear about the things ‘John Wayne’ stood for.

Comments powered by CComment